Home » 2024 Icons: Itron Inc.'s Johnny Humphreys

2024 Icons: Itron Inc.'s Johnny Humphreys

Companies grown by longtime tech exec remain vibrant today

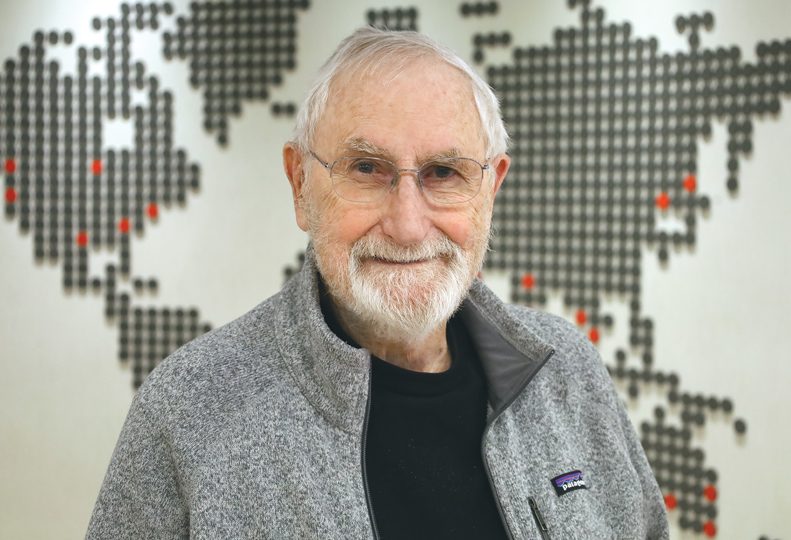

Johnny Humphreys, shown here at Itron Inc.'s present-day corporate headquarters in Liberty Lake, led the company from 1987 to 2000.

| Linn ParishMay 9, 2024

When a recruiter approached Johnny Humphreys about leading a Pacific Northwest tech company nearly 40 years ago, he thought a move to Seattle or Portland might suit him.

It wasn't until the day before he was supposed to leave the Silicon Valley for the interview up north that he found out it would be with a company in Spokane.

"I said, 'Where's Spokane?'" recalls Humphreys, now 86 years old.

Leaving what he describes as the "monotonously wonderful weather of Northern California" and arriving in snowy Spokane, he was unsure he wanted to be CEO of Itron Inc. and claims he interviewed poorly.

But the more he learned about the young company that made meter reading technology, the more appealing the job became. After Humphreys compelled a one-on-one second interview of sorts with Paul Redmond, who led Washington Water Power Co. at the time and served chairman of its Itron spinoff, he was offered the opportunity to lead the company and accepted.

When Humphreys became Itron's CEO in 1987, the company had $20 million in annual revenue, but a $5 million operating loss and a murky path forward. By the time he retired in 2000, the company was publicly traded and had roughly $280 million in yearly sales.

Twenty-some years and a handful of acquisitions later, the utility-tech company has $2.1 billion in annual revenue, more than 8,000 customers in 100 countries, and more than 5,000 employees worldwide, including 455 at its Liberty Lake-based corporate headquarters.

"He really grew the company exponentially," Redmond says now. "We were very fortunate in the Spokane area to be able to bring a Johnny Humphreys in."

To fully understand Humphreys' value as an executive, Redmond and others say, one has to concede a common dilemma in the tech sector—and arguably the startup community as a whole—that can limit a company's ability to grow or remain solvent. Frequently, founders have skills and expertise in a technical field but lack business acumen.

"In his case, he had the qualities to do both," says Redmond, who served as CEO and chairman of Washington Water Power, now Avista Corp., from 1985 to 1998.

Those qualities are one reason that Humphreys has been in demand to serve on boards for Spokane-area startups since retiring from Itron. Companies he guided—and invested into, in some cases—include Linesoft Corp., which made software for power line planning and design; Pacinian Corp., which developed touch-screen technology; and biotech GenPrime Inc.

"One of the things I found out is I'm better at building companies than I am at advising," Humphreys says. "When you're running a company, you're really in tune with the customers and what's needed. When you're on the board, you're listening to what management is telling you, and you're giving advice that may not fit."

Darby McLean, CEO of Spokane-based spice maker Spiceology Inc., disagrees with Humphreys' insinuation that he isn't a good adviser, but says she can understand why it might feel that way to him.

"When you’re advising, you’re trying to give them the tools. It's the teach-a-man-to-fish analogy," McLean says. "But when you’re a fantastic fisherman, it’s easier to just catch the fish."

McLean worked as a project scientist at GenPrime when Humphreys served on the board, as well as when he took over as CEO for a couple of years. During his tenure, she says, he taught a group of employees with backgrounds in science how to develop a sales strategy, how to take products to market, and how to read a profit-and-loss statement.

After a couple of years, he turned the CEO role over to one of the people he'd mentored.

McLean credits Humphreys with giving her skills to take on C-level roles and says he's the greatest contributor to her business education. She adds that she's not unique in that regard.

"Look at some of the professionals that he mentored. You’ve got people who are operating at a really high level throughout the community," she says.

Discovering engineering

While Humphreys developed both technical and business-management skills, his career started with an engineering background.

A Henrietta, Texas, native, Humphreys started his career working for a utility in the nearby, larger town of Wichita Falls and going to school part-time at the University of Texas at Arlington through a program offered by his employer. There, he was exposed to engineering.

"When I went in there and learned about engineering, that was the first time I knew what I wanted to do," Humphreys says.

Shortly after beginning his education, Humphreys landed a part-time job with Texas Instruments Inc., which turned into a full-time job. There, he worked in research and development, making low-power products for NASA using silicon transistors.

The technology was changing rapidly at that time, he says, and he left Texas Instruments to join Gulf Aerospace, where he worked his way up to being the "No. 2 guy" in the company.

In 1967, he struck out on his own to start Electronic Laboratories Inc., in Houston, which developed a handheld computer used in inventory management and product ordering in the grocery industry.

That company had grown to about $20 million in annual revenue when Humphreys left, disgruntled after a dispute with venture capitalists he had brought on. After his departure, the company was renamed Telxion Corp. It went public and later was acquired for $600 million.

"I left way too early, relative to what they achieved," Humphreys says. "But I'm pretty proud of them, because it was my plan and the people I hired that carried it through."

In 1975, he moved to the Silicon Valley and joined Datachecker, a young subsidiary of National Semiconductor that was developing the technology for scanning items at retail stores, specifically supermarkets—technology that's largely the same as what's used in checkout lines today. Humphreys started out leading the marketing department there and ascended to the president's role during his 12 years with the company. During Humphreys' tenure as president, Datachecker acquired a competitor and grew to $200 million in sales.

Like Electronic Laboratories, Datachecker later was acquired. Some iteration of both companies is still in operation.

Humphreys describes his management style as one that emphasized consensus building and putting the right people in the right positions.

"You can go two ways," he says. "You can get people to help you develop a vision, or you can say, 'I'm the smartest guy in the room, so I'm going to hand you a vision.' Well, good luck on executing on that."

Today, Humphreys is focusing his energy on a completely different sort of venture: developing the Whitetail Ridge neighborhood on a 72-acre piece of land he and his wife, Janet, have owned just south of Spokane Valley for about 30 years. When fully developed, Whitetail Ridge is expected to have 118 homes on 72 acres of land, with a total value of about $83 million.

"Every time I say I'm retired, my wife just laughs," he says.

Through the years, the pair has developed an appreciation for Spokane, and while they didn't plan to stay after the Itron stint, Humphreys says neither can imagine going back to California now.

And he says he doesn't think they're alone in their attraction to the Inland Northwest.

When he first moved to Spokane, he says he had to guarantee engineers he recruited to Itron from northern California that he'd pay to move them back to Silicon Valley if they didn't like it here. At the time, he says, Itron provided the only employment opportunity for such professionals, so such a move to the Inland Northwest came with risk for those workers.

Humphreys never had to pay to relocate any of the people he recruited here, and he says some of them went on to start their own companies here.

Now, highly skilled employees have more options for employment in the Inland Northwest and aren't necessarily tethered to one company.

"I don't know exactly when that changed, but I think we've achieved critical mass," Humphreys says. "It's a gradual thing. It wasn't a light switch."

Icons Latest News Up Close Manufacturing Technology

Related Articles

![Brad head shot[1] web](https://www.spokanejournal.com/ext/resources/2025/03/10/thumb/Brad-Head-Shot[1]_web.jpg?1741642753)