Improving hip, knee replacement technology

WSU researchers received six patents in last two years

For almost two decades, Washington State University researchers Amit Bandyopadhyay and Susmita Bose have worked diligently to improve the materials used in hip and knee replacements that up to a million people in the U.S. receive each year.

In the 1990s, the research team was studying rapid prototyping, or 3-D printing as it is commonly known—before most of us even knew what it was. A decade later, they started working with powders at the nanoscale and printing out customized hip bones from computerized images in their laboratory.

“When we started, there were many nonbelievers,” says Bandyopadhyay, a professor in WSU’s School of Mechanical and Materials Engineering. “The first 10 years were spent converting the nonbelievers to believers. Then, we worked to convince industry it can be successful. Now people realize it’s real.”

In the past two years, the researchers have received six patents on technology that could improve recovery time and outcomes for the common surgical procedures. Their ideas include porous metal or biomaterial-based implants, new drug delivery systems, and infection control using silver.

In the last couple of years, they also have edited two books on biomaterials and additive manufacturing, or 3-D printing, and are working on two five-year National Institutes of Health grants. Along the way, they have provided training for more than 60 graduate students and have garnered prestigious national and international recognition. That recognition includes Bose’s Presidential Early Career Award, the nation’s highest early career science award given by the U.S. President at the White House, and Bandyopadhyay’s recent election to the National Academy of Inventors.

Their work promises to become increasingly important in the years ahead as the U.S. population ages and looks for better solutions for their arthritic joints. In addition to age-related bone and joint problems, people often need orthopedic surgery for other illnesses, such as cancer or rheumatoid arthritis—or for injuries.

For most hip and knee replacement patients, surgeons use an acrylic bone cement to affix titanium implants in the body. Doctors borrowed the idea of using titanium from the aviation industry in the 1950s, but the material doesn’t match well with human bones and tissue.

While patients are often out of bed and walking within a day or two of surgery, the materials used in implants are foreign to the human body. They don’t bond strongly to surrounding tissues, resulting in typical implant failure within 10 to 15 years. The technique, which has remained largely the same for more than 40 years, can be problematic for younger patients or those who need revision surgeries. Infection after surgery also is often a concern.

With the NIH grants, the researchers are working to improve the coatings for the titanium-based implants using bone-like material, so that they will attach better to surrounding tissue, act more naturally within the body, and last longer. The coatings create a natural-feeling surface on the implant.

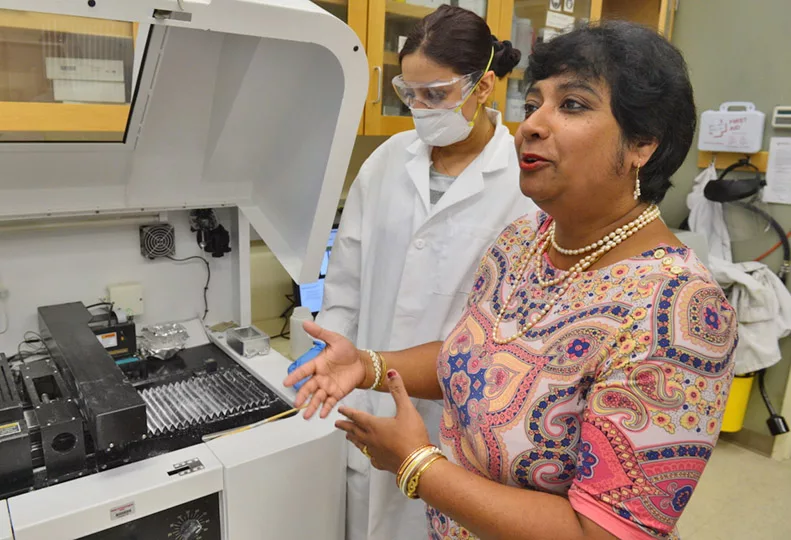

Bose, who also is a professor in the WSU School of Mechanical and Materials Engineering, is leading research to mix ions commonly found in the body, such as magnesium, zinc, and calcium, into the bone-like calcium phosphate coatings.

Her team also is adding tiny amounts of medicine, such as antibiotics or osteoporosis medications, to the coatings. The researchers have found that their coatings with added minerals, or dopants, have better integration into the body than typical coatings.

They also are working to understand the mechanisms at the cellular level to understand how the materials improve bone growth and integration. The researchers also have added and are testing silver in the coatings. The silver can be released slowly into the body to control infection.

Bandyopadhyay’s group, meanwhile, is working with porous metal coatings for the implants using 3-D printing technology. Using an idea reminiscent of Chia Pets, the researchers are dunking porous, metal-coated implants in an electrochemical solution and then growing tiny nanotubes of metal on the surface. The researchers have found that the tiny nanotubes act as anchors, enabling the implants to bond more strongly to surrounding tissue. The researchers also are studying the ideal parameters for making the coatings and looking into the best manufacturing methods.

Bose and Bandyopadhyay recently published a new textbook, “Materials and Devices for Bone Disorders.” The text provides a unique, multidisciplinary approach to the biomaterials and biomechanics of bone implants, with input from a variety of experts in engineering, medicine, ethics, and the medical industry. The text can be used as an introduction to materials for a medical school, in bioengineering courses to provide a physician’s perspective, and in mechanical and materials engineering courses to help students better understand commercialization. There is even a chapter on prevention that discusses how to avoid such surgeries by developing better health habits.

“I am very passionate about bone health,” says Bose.

The researchers hope that someday soon the technology they have developed will become available and might help people as they face getting a new hip or knee.

And, when might that be? Well, the researchers say they plan on sticking to research.

“My simple answer is that there are things we do, and things we don’t,” says Bandyopadhyay.

They plan on continuing their work in the laboratory and the classroom and look forward to entrepreneurs who can move forward with developing their technology for the market.

Tina Hilding is communications director at the Voiland College of Engineering and Architecture at Washington State University in Pullman.

Related Articles

_c.webp?t=1763626051)

_web.webp?t=1764835652)