Home » Taking 3-D printing to heart

Taking 3-D printing to heart

Pediatric cardiologists use patient models to test procedures

July 6, 2017

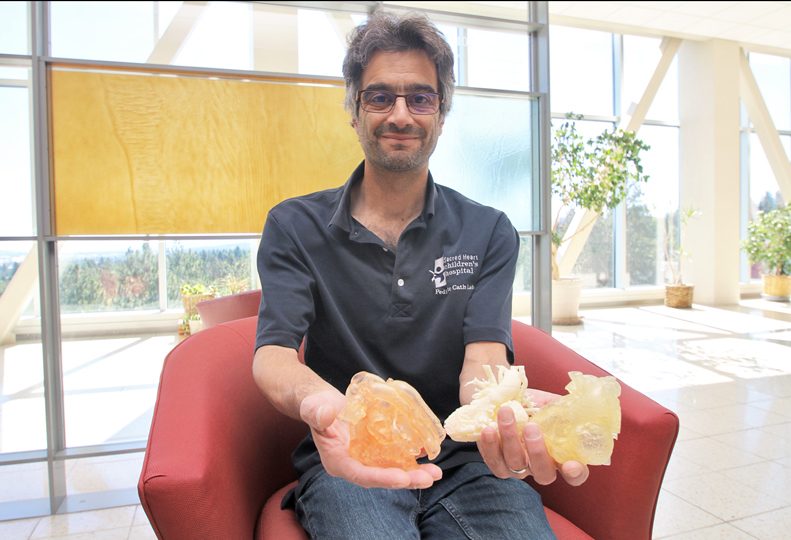

Dr. Carl Garabedian and other Spokane pediatric heart physicians are pioneering the use of 3-D printed models to plan and practice complex heart procedures.

The physicians, who work at the Providence Center for Congenital Heart Disease clinic at Sacred Heart Children’s Hospital, typically are practicing for procedures to be performed on children and adults born with heart abnormalities, Garabedian says.

The first use of the model here was for a child patient named Nate. His parents, who adopted him when he was 2 years old, had noticed that it didn’t take much activity for Nate to become tired and short of breath.

Doctors soon discovered he had been born with a severe heart defect in which the aorta was attached to the wrong part of the heart, meaning the main artery that supplies oxygenated blood to the circulatory system was far removed from the chamber of the heart that’s supposed to pump blood into it, Garabedian says.

Adding even more complexity to the diagnosis, Nate also had severe narrowing—called stenosis—under his pulmonary valve, further restricting blood flow.

“It was very complicated,” Garabedian says, adding that he believed 3-D printing would help in visualizing Nate’s heart abnormalities and in planning treatment.

Garabedian says he had heard about medical applications of 3-D printing technology during meetings with other pediatric heart specialists.

“We pediatric cardiologists are a small group throughout the country,” he says. “We talk to each other, and we’re always thinking of ways to do a better job of taking care of kids with heart diseases. The reality is that these more complex patients end up getting much more complex problems than we’ve have to deal with. Learning about those problems can be even more challenging despite all the improving imaging techniques that we have.”

Each model can cost over $1,000, and the technology isn’t covered by insurance. The clinic however, secured funding for Nate’s model and a few others through the Children’s Miracle Network Hospitals of the Inland Northwest, a nonprofit partner with the fundraising arm for Sacred Heart Children’s Hospital.

Sacred Heart Children’s Hospital is an entity of Providence Sacred Heart Medical Center, at 101 W. Eighth.

The hospital sent data compiled through 3-D imaging computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging equipment to Materialise, of Plymouth Mich., which ran the data through its proprietary surgical planning software and hardware to assemble a 3-D model of Nate’s heart.

“With 3-D technology, it’s been helpful for us to see the anatomy of the heart in a three-dimensional way,” Garabedian says. “Initially it was great just to have 3-D renderings on a computer screen that you can spin and move, but sometimes the anatomy is so complex that you really need to have a heart in your hand.”

With the model, Garabedian and Nate’s cardiology team were able to make decisions about which procedure to conduct, plan for it, and even practice the complex procedure in advance of Nate’s operation, he says.

The procedure was successful, and Nate is now a normally active and energetic 5-year-old, he says.

“Nate is doing great,” Garabedian says. “I see him, but I see him infrequently because he’s doing so well.”

Garabedian says he’s performed seven procedures with the aid of 3-D printed models in less than two years, and the Providence Center for Congenital Heart Disease clinic, which has seven other pediatric heart physicians, has conducted a dozen procedures employing 3-D printed models beforehand. Two more procedures are in the planning stages.

Garabedian says interventional cardiologists, such as himself, and cardiac surgeons spend a lot of time with the models to become familiar with the anatomy and to plan complex surgical and heart catheterization procedures.

“This is a way to really test what you’re going to do to make sure it’s going to work,” he says.

The rest of the patient’s surgical and care team also see the model, he says. “The whole team is taking care of the patient after surgeries, so it’s very important and instructive for them to understand the anatomy we’re treating,” he says.

The 3-D printed model can be made with different materials. Some materials are rigid and brittle, and some are soft and pliable.

The soft plastic is more like real tissue, Garabedian says.

Patients also are fascinated with the models of their own hearts.

“They love them,” Garabedian says. “Sometimes I let them take them home. I think Nate has his own.”

Garabedian says he’s also employed 3-D printed models for adult patients.

Adult congenital heart disease is a new subspecialty, although Garabedian says there are now more adults than children with congenital heart disease.

“That tells you we are very good at what we do as pediatric cardiologists, because now these kids are growing up and becoming adults,” he says.

One congenital heart patient he’s working with is 58 years old and needs a unique procedure to correct an abnormality that’s a complication of childhood heart surgery.

Garabedian is working with a model to plan that case and will collaborate with a physician from UCLA to perform the procedure.

Garabedian says the hospital here is vying to become one of the first accredited adult congenital heart disease centers in the country. He says the medical center is among 15 hospitals going through the accrediting process.

“We have all the components we need here,” he says.

Kirsten Carlile, spokeswoman for Children’s Miracle Network Hospitals INW, says the 3-D heart model is one of many projects that the organization funds.

“Carl came to us with this idea and said it would make a big impact,” Carlile says. “We said, ‘We’re in.’”

The organization has funded four 3-D models for Sacred Heart Children’s Hospital heart patients, and has produced a video that shares Nate’s story.

“We have world-class health care, but health care is expensive, and these things impact patients’ lives,” Carlile says.

Last year, the Children’s Miracle Network INW raised $1.2 million for the Providence Health Care Foundation to use toward Sacred Heart Children’s Hospital patients, research, and children’s health issues.

Carlile says donations raised here by Children’s Miracle Network stay in the community.

“As fundraisers, our job is to connect the community to hospital,” Carlile says. “When people see balloon (logo), they can know the money stays local.”

Children’s Miracle Network INW has a staff of one full-time employee and two part-time employees based at Sacred Heart Children’s Hospital.

The Utah-based nonprofit is partnered with 170 children’s hospitals, and also raises funds for medical research and children’s health issues.

Sacred Heart Children’s Hospital is one of three hospitals in Washington state designated as a Children’s Miracle Network Hospitals partner. The others are Yakima Valley Memorial Hospital and Seattle Children’s Hospital.

Latest News Special Report Health Care Technology

Related Articles

Related Products