Home » All That And A Lack of Chips

All That And A Lack of Chips

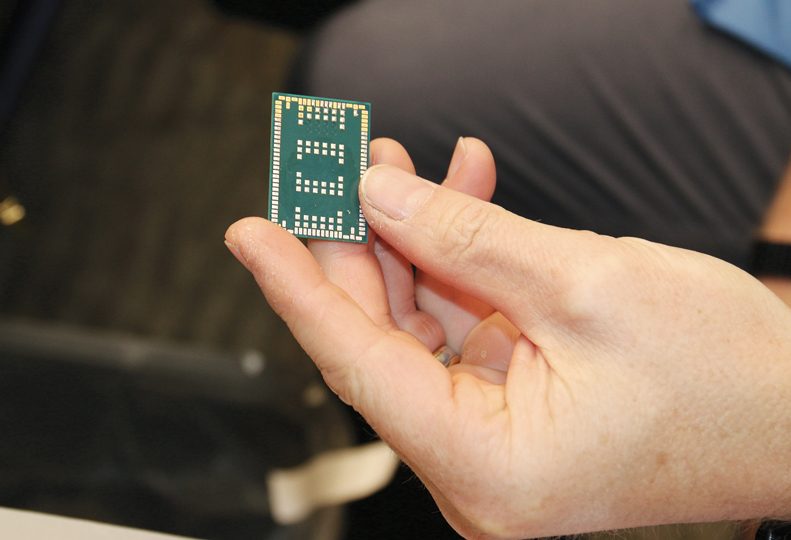

Global supply disruptions wreak havoc on local semiconductor availability

May 6, 2021

Tate Technology Inc. President Scott Tate doesn’t consider himself to be an alarmist by any stretch.

But for a number of months, the head of the Spokane Valley-based contract manufacturing company has been issuing warnings to his customers about parts shortages, specifically involving computer chips and semiconductors.

“If Honda can’t get parts, then Tate Technology is not going to get parts,” he says. “We’re at the bottom of the food chain.”

A global shortage of microchips and semiconductors—the brains of all electronic devices, ranging from cell phones to automotive dashboard systems—was fueled by stoppages in production last year due to factory plant closures following the worldwide spread of COVID-19.

Even though microchip manufacturers are mostly back in business, manufacturing industry experts are sounding the warning that a months-long backlog of orders won’t be cleared anytime soon.

“We’re trying to educate and inform our customers—and their customers—that there is a global supply chain crisis going on,” Tate says. “And it’s going to take a while to get sorted out.”

While there’s a supply-chain backlog, there’s no shortage of work. Despite the pandemic, Tate says revenue only fell by 1% in 2020 from 2019.

The backlog of computer chips and semiconductors is exacerbated by the high demand of such parts required from the automotive industry in the making of new vehicles, something that also largely came to a standstill in 2020.

Scott Brewer, the general manager at Lithia Auto Stores, at 10701 N. Newport Highway, in North Spokane, says the lack of new vehicle inventory has driven used car purchases to unprecedented heights.

He says new vehicle inventory is about a third of what it was before the pandemic’s arrival, and sales revenue were up between between 200% to 250% compared with sales in March of 2019 and 2018.

Derrick McGee, a sales consultant with BMW of Spokane, at 215 E. Montgomery on the North Side, says he’s on pace to exceed every sales record he’s ever reached in his 2 1/2 years of employment at the dealership.

“It’s definitely put me in another tax bracket,” McGee says.

Tate says that the shortage of computer chips for new cars may have helped fuel the used-car industry, but it has created headaches in other industries.

Located in an 18,000-square-foot building formerly occupied by a Great Floors flooring store at 5716 E. Sprague, Tate Technology’s 45 employees spend most days in a climate controlled, dust-free environment manufacturing circuit boards for its customers, most of which are in the telecommunications industry, he says.

On March 18, Tate sent an email to the company’s customers notifying them of supply chain problems.

“This is due to several factors including reduced outputs from COVID, global weather impacts, and increased demand in consumer electronics and automotive. The component industry expects this problem to get worse before it gets better,” Tate wrote.

Tate also provided nearly a dozen online links to articles and reports written by industry experts about the shortages.

In an article that appeared in Forbes last month, Dave Opsahl, the CEO of Santa Rosa, California-based software company Actify Inc., says the auto industry dramatically slashed computer chip purchases in response to pandemic-related plant closures but then mistakenly believed production could be ramped up just as quickly.

“I doubt that any industry could respond effectively to that kind of demand fluctuation, but since semiconductors can have a production lead time as long as 26 weeks, there was no chance,” Opsahl writes.

He also makes the point that the automotive industry’s shift toward autonomous and electric vehicles has put more pressure on electronics component makers.

“It may have taken a perfect storm of a global pandemic, geopolitical challenges, and significant transportation disruptions, but it has exposed the fact that cars and light trucks are rapidly transforming into electronic devices,” Opsahl writes.

In another article, the Electronics Components Industry Association, a major trade group, estimated lead times will only grow in 2021 for obtaining a broader range of electronic components amid the global shortage.

Tate says he’s concerned for local companies that still haven’t submitted orders for parts, including chips and semiconductors.

“We’re receiving multiple notifications from manufacturers and distributors warning of depleted inventory, long lead times, and increased costs,” he says. “Many jobs on our schedule have already been impacted.”

He’s urging business owners to be patient with their vendors and to be proactive in notifying customers of potential delays.

“The good news is that in our market, most of our competitors are good,” Tate says. “For the most part, if you’re still around after last year’s recession, you probably know what you’re doing, and you have good folks working for you.”

However, Tate says he’s fielded no shortage of inquiries from competitors asking if Tate Technology can help them fulfill their customer requests.

Last week, he declined three projects from a competitor that would have taken too much time to complete on the part of the company’s staff, he says.

“It’s a good problem to have when you rewind to a year ago. This is the opposite problem,” Tate says.

He urges his customers to review their existing inventory, forecast, and open orders and plan far in advance.

“If, as an example, a previously quoted lead time was six weeks, it could now easily be 16-plus weeks due to a single component shortage,” Tate says.

Latest News Manufacturing Technology

Related Articles

Related Products

![Brad head shot[1] web](https://www.spokanejournal.com/ext/resources/2025/03/10/thumb/Brad-Head-Shot[1]_web.jpg?1741642753)