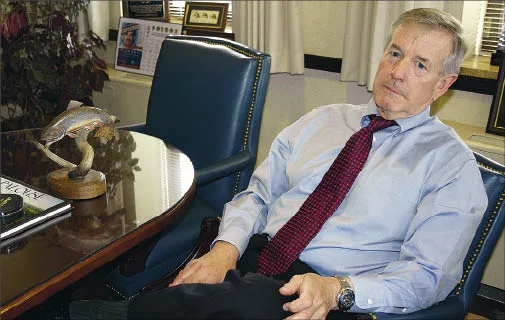

U.S. attorney to successor: 'Don't pass this up'

After eight years on the job, McDevitt believes there's big need for crime prevention

When James A. McDevitt, the U.S. attorney for Eastern Washington, heard that Spokane lawyer Mike Ormsby had been nominated to be his successor, he called Ormsby and said, "'Don't pass this up.'"

It's simple, says McDevitt, who's been a lawyer for 35 years. "I've enjoyed this more than anything else I've done in the legal profession. One of the satisfying parts of this job is the difference that you're making and your people are making every day."

What isn't so simple is when McDevitt's term will end. Orsmby's nomination for U.S. attorney is one of many on hold in the U.S. Senate.

McDevitt took the job in 2001. "Eight and one-half years later, I've learned that we can't prosecute our way out of crime," he says. "We need to put as much time, effort, and money into crime-prevention programs as we do into prosecution."

McDevitt and his team have brought such prosecutions as the so-called "Gold Seal" case, in which six violators who had awarded 10,800 phony diplomas to 9,600 recipients in 131 countries pleaded guilty, and their lucrative diploma mill shut down.

They've sent to prison a Spokane man who sold phony railroad parts, an osteopath who prescribed oxycontin and oxycodone illegitimately, and a Yakima bank manager who intimidated subordinates into disregarding internal controls as she embezzled nearly $564,000.

They've nailed a Spokane hospital warehouse supply supervisor who stole inventory items and sold them on eBay, raking in almost $700,000. They've exposed a Washington state Department of Social and Health Services contractor and his wife who set up a phony child-care program to receive state and federal foster-care monies meant for developmentally disabled children.

"It is not a waste of time to vet people, vet degrees, check references, or do background checks," McDevitt says. He also urges businesses and others to work with financial institutions to circumvent identity theft. He says customers should ask their bank to require them to enter a PIN number or a ZIP code when they use their credit cards.

"At least 50 percent of the crimes we investigate now are in some way electronically facilitated," whether it's with a cell phone, the Internet, Twitter, a Blackberry, or by some other means, he says.

The job of U.S. attorney, which pays $155,500 a year, entails prosecuting criminal cases brought by the U.S. government, prosecuting and defending civil cases to which the U.S. is a party, handling criminal and civil appellate cases before the U.S. Court of Appeals, and collecting debts owed to the U.S. government. The U.S. attorney is appointed by the president and confirmed by the U.S. Senate and reports to the U.S. attorney general.

The eastern district of Washington encompasses 20 counties, has 1.4 million residents, and lies east of the Cascade crest.

McDevitt grew up in the Seattle area and attended the University of Washington. During summers, he worked for the Washington state Department of Natural Resources, as a truck driver, boss of a 20-man fire crew, and a forest warden. After graduating, he served on active duty for five years in the U.S. Air Force, eventually becoming a weapons systems officer in the two-seat F-4 Phantom fighter, spending four relatively brief tours in Vietnam during the war there, and visiting other global hot spots.

After his active-duty military service, McDevitt came to Gonzaga University to earn a law degree and a master's in business administration, and the Washington Air National Guard offered him a job here as an instructor in the rear-seat operations of the F-101 Voodoo fighter. Later, he flew in air tankers as a navigator and became an Air Guard commander, retiring as a brigadier general after a 30-year career. A private pilot, he and a partner own a small plane equipped with oversize tires for landing on backcountry airstrips, and his flying has helped him learn his district in detail and find remote locations to fly-fish, which is a passion.

In May 1975, he passed the bar exam and received his MBA. He and his wife, Gretchen, a Spokane Public Schools teacher, decided to stay in Spokane rather than return to Seattle, partly because of the outdoor opportunities here. The couple has two sons.

McDevitt joined then-Washington Attorney General Slade Gorton's staff and stayed for 2 1/2 years, handling consumer protection, antitrust, and white-collar crime cases and providing legal advice to community colleges. He then joined the Spokane law firm of Reed & Gieisa PS and later moved to Preston Gates & Ellis LLP, now K&L Gates LLP. He says he enjoyed private practice and mostly worked in corporate law, sometimes handling international transactions.

To do a good job in Eastern Washington, the U.S. attorney must run a good office and stay connected" with other law-enforcement officials, McDevitt says. His office has 20 attorneys, 21 staff members, and nine law clerks in Spokane, and seven attorneys and five staff members in Yakima. He also has an office in Richland that one of his Yakima attorneys staffs part time.

"We have 27 of the brightest, best lawyers who love what they do," McDevitt says. He says that except for retirements, the office has almost no turnover. Currently, one staff attorney is on a voluntary assignment in Baghdad, investigating war crimes and helping Department of Justice lawyers. Another is in Tbilisi, Georgia, helping that emerging democracy train prosecutors and rewrite its criminal code. McDevitt hires temporary replacements.

The U.S. attorney wields complete discretionary power on bringing charges in the district, although in most cases a grand jury decides whether to indict a defendant with a crime. The downside of the position is that "sometimes people criticize your decisions," he says.

Within six months after he took the job, he had visited every county in the district, meeting every sheriff and county prosecutor and all 85 town marshals and police chiefs "from Asotin to Zillah," McDevitt says.

"You start building partnerships and relationships. I can reach out on a gang sweep and call a county sheriff and say, 'We're going to form a task force. Can you help out?'"

The electronic records systems of all local, state, tribal, and federal law-enforcement agencies in five states are linked to a master computer at the FBI's offices in Seattle, and those links have paid big dividends, such as when a murder suspect who had fled Tacoma reported that his car had been burglarized elsewhere in the state. A crime analyst saw the report, resulting in an arrest.

Right now, outdoor marijuana-growing operations are one of the biggest law-enforcement problems in the district, McDevitt says. In 2009, of the 240 people arrested in marijuana-growing operations in the state, 90 percent were nabbed in Eastern Washington, and 90 percent of those arrests occurred at outdoor locations, he says. Agents destroyed 610,000 marijuana plants in Washington, second only to 3 million plants in California.

Washington is an intersection for drug smugglers from Canada, who bring potent "B.C. Bud" marijuana and the drug ecstasy across the border, and smugglers from Mexico, who send cocaine, cash, and guns the other way. Mexican smugglers bring large quantities of methamphetamines to Washington to fill a supply void created when law enforcement closed 180 meth labs in Spokane County in 2002 and 2003, McDevitt says.

Mexican drug traffickers finance the outdoor marijuana-growing operations, McDevitt says. "Grow tenders," who are dropped off at remote trailheads, have no idea who backs the operations. A contact drops off fertilizer, insecticides, and other supplies periodically and picks up harvested marijuana.

The growers know they'll get paid only if they deliver drugs, and they pose a threat to the public's safety, McDevitt says. During busts at grow operations in Washington last year, agents recovered 170 guns. In California, grow tenders and agents engaged in a shootout last year, and a grow tender's cooking fire ignited an 80,000-acre forest fire.

The operations pollute sites with human waste, pesticides, insecticides, and other garbage, and the U.S. Forest Service estimates it costs $4,000 to $6,000 an acre to restore them, McDevitt says. Four of the outdoor growing operations busted in Washington last year were in the Methow area, "one within a half-mile of Sun Mountain Lodge," he says. Others were in the Colville and Wallula areas and on the Yakima Tribe's reservation.

"I think it will abate when we make a dent in the demand," McDevitt says.

Related Articles

_c.webp?t=1763626051)

_web.webp?t=1764835652)