Home » Getting a grip on FINGER PAIN

Getting a grip on FINGER PAIN

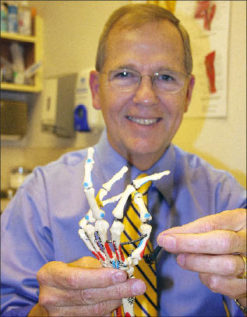

Rockwood Clinic surgeon uses carbon-coated prosthesis to restore finger-joint function

June 17, 2010

Rockwood Clinic PS orthopedic surgeon Dr. Wayne Venters is implanting a prosthetic finger-joint here that he says has been a long-lasting and less traumatic alternative to bone fusion for patients who suffer from debilitating problems in the middle joints of their fingers.

Though not approved for regular use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, the PyroCarbon proximal interphalangeal (PIP) prosthesis can be used on a study basis as a humanitarian device, because fewer than 4,000 of the surgeries are done in the U.S. each year, Venters says. The device is made by Ascension Orthopedics Inc., of Austin, Texas.

Venters says he registers his practice as a study site for the prosthesis because people who have lost use of that joint or have extreme pain at a fairly young age can benefit greatly from the device, and it's not available except through a registered study site. Conrad Harder, a representative here for Ascension, says Venter currently is the only physician in Spokane using the PyroCarbon PIP implant, though a plastic surgeon here did two of the implants in the past.

The prosthesis, which Venters describes as being like a "squirrel-sized" total knee replacement, can be implanted into a patient's finger in a 90-minute outpatient surgery that requires general anesthesia.

Venters performs the surgeries at Rockwood Clinic's ambulatory surgery center, as well as at Providence Sacred Heart Medical Center & Children's Hospital and at Deaconess Medical Center.

After having done about 25 of the procedures over the past few years, Venters says the device is proving useful and longer lasting than most of the other alternatives available to patients with finger joints that are so stiff due to rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis or injury that they can't grip an object, or who suffer terrible pain.

Without a prosthesis, the "gold standard" for treatment in such cases, when less invasive treatments such as medication and therapy fail, is fusing the bones on either side of the joint together, which reduces pain but leaves a person without functional use of the finger for gripping, he says.

Venters says that because the cost of the procedure is relatively high—about $20,000 including the surgery, the prosthesis, and the anesthesia and related costs—it isn't warranted unless a person is fairly young and will need use of the joint for many years.

Likely candidates for the surgery include patients who have lupus or psoriatric arthritis, who can be fairly young. Other candidates might have post-traumatic osteoarthritis, such as a former basketball player whom Venters says had terrible chronic pain and joint stiffness after many sports-related injuries. The middle finger of the non-dominant hand is most commonly operated on, but Venters has some patients who have several of the PIP prostheses.

In the procedure, a surgeon opens up the finger to the bone surface with a longitudinal incision, bends the finger at the incision, shears off the surfaces of the ends of the bones near the joint, and removes the remaining bone that served as the rest of the joint. Bending the finger moves the ligaments on either side of the finger out of the way to reduce damage to them during the procedure, Venters says. Once the ends of the bones are sheared off, the surgeon uses an awl to create a canal in the end of each of the sheared bones, into which a portion of the implant will be placed.

Once the implant is placed, the doctor tightens the ligaments on either side of the finger to ensure a properly working joint, and closes the incision. Following the surgery, the patient wears a splint for a month and undergoes several months of physical therapy, Venters says.

So far, he hasn't had to remove any of the prostheses due to wear, though he did replace one joint with a different size, and replaced another when a patient injured herself, damaging the first prosthesis, he says.

Low-friction material

The PyroCarbon PIP is one of a line of prosthetic orthopedic devices that Ascension produces using PyroCarbon coating on a graphite prosthetic joint. The coating makes the joint very slick, so little friction occurs within the joint, and thus also very little wear, Harder says. He says the material has been used in heart valves for years, but Ascension uses it as a coating for orthopedic devices.

Harder says Ascension had wanted to get the product approved for use in the general market, but has focused instead on seeking FDA approval for some of its other joint replacements that are more widely used, so it sought the humanitarian approval for the device. For each orthopedic device Ascension develops, it must get FDA approval for the device first, then for the device combined with the PyroCarbon coating, he says.

The PyroCarbon devices are created by putting graphite prostheses into a 1,300-degree heat chamber, and blowing a special formulation of carbon, called radiolucent carbon, into the chamber, where it adheres to the exposed surfaces of the prostheses. Only the ends of the prostheses that rub against each other or against bone are coated.

The portion of the implant that is inserted into the bone has a rougher surface that allows tissue to grow onto it, but not into it, eliminating the need to use cement to fix the implant into the bone, Harder says. This makes it easier to remove later if it needs to be replaced.

There are a few other prosthetic devices in use for middle finger joints, all made of silicone, steel, or titanium. Those materials can be problematic, Venters says.

For instance, he says, silicone joints are easily broken, and generally have lasted little more than a year for many patients. The metal joints, meanwhile, are actually harder than bone, which means they can damage the bone with the frequent use a finger gets, and ultimately fail.

"PyroCarbon so far has been really good," as an alternative to previous materials, Venters says. He says it appears to give patients good range of motion, though it's not as good as the original healthy joint would be. Also, PyroCarbon is about the same density and weight as bone, so it works well with the surrounding skeleton, he says.

"It doesn't have a hinge, so there's nothing to break," Venters says.

Harder says Ascension recently has introduced a new joint replacement for the carpal joint on the thumb, which will fit more naturally, and the company is in the process of seeking FDA approval for several other prostheses, including a radial elbow joint replacement.

Latest News

Related Articles