Home » Retirement executives here lend hand in Cook Islands

Retirement executives here lend hand in Cook Islands

During annual vacations, couple provide training, medical supplies, activities

July 15, 2010

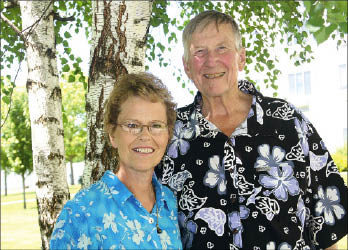

Ron and Alice Semingson thought they'd get away from their management jobs with an assisted-living chain when they traveled to the Cook Islands 13 years ago for a tropical vacation, but failed to avoid work completely. Rather, they found enormous need for their services among the aboriginal Maori residents of the islands, and they haven't stopped going back since.

The Semingsons worked for a Dallas company when they made their first trip, but now own the Rose Garden Estates assisted-living center in Ritzville, Wash., and Ash Geriatric Services, a Deer Park, Wash.-based geriatric consulting business. Every January and February, they return to the Cook Islands, a New Zealand island protectorate stretched across 2 million square miles of the South Pacific near the equator. The weather is in the 80s.

When they make their trips, the Semingsons take along four of the biggest suitcases they can find at thrift stores here, jammed with medical supplies, while packing all of their personal items in their carry-ons.

"When you go to the tropics, you don't need anything but a swimming suit and a couple of shirts," says Ron Semingson, 72. When they return home, they leave the old suitcases behind.

The Semingsons' interest in the needs of the Cook Islanders started when they disembarked from their first flight to Avarua, on Rarotonga, a 26-square-mile island that's the Cook Islands' population center, with 14,000 residents, and is the home of its Parliament.

The Rotary Club had put out a donation box in the "air terminal," really just a roofed walkway with no walls, and asked travelers to donate their change for the opening of an "elder house."

"We contacted the Rotary. We asked, 'How can we help you? We do this for a living,'" Semingson says.

The Rotary Club had acquired a building, where elderly Maori women made their lunch and sat together after they were brought to the center in a van. Once a week, the pastor of the Cook Island Christian Church conducted a Bible study for the "mamas," as the elderly women are called, but there were no other activities. The Semingsons thought, "Let's develop an activity program," he says.

They suggested that the church arrange visits to the mamas by members of the congregation, and it did so. They talked with local people about what the mamas might need and learned the women loved old Western movies and musicals. The Semingsons bought a VCR for the elder house, and movies became a focal point of the day, Semingson says.

"We had fun that week," Semingson recalls. "We got on the plane home and committed ourselves—'Let's come back until we're tired of it.' You reach a point in life when it's time to give back. The needs were monumental."

Back home, he says, "It plays on your mind, on what you can do for them." The Semingsons scoured yard sales for videotapes of musicals and Westerns starring John Wayne, a favorite of the mamas, and carried the videotapes with them when they returned. The activity program now includes weaving of straw hats, done somewhat differently on each island, and the making of flower aies, much like Hawaiian leis. A retired nurse comes to the center every day. "It is the only facility in the Cook Islands that takes care of their elders that way," Semingson says.

During the Semingsons' second trip, a doctor invited them to tour the local hospital, which is "circa 1920," Semingson says.

They noticed the hospital's equipment was old, and asked the physician for a shopping list of things the hospital needed. The Semingsons learned that the islands have shortages of even basic medical supplies. Back in Spokane, they called Roy Hurford, the owner of Pacific Northwest Medical Supply. Hurford invited them to his warehouse and contributed "a pickup load" of items, including bandages, catheters, pads for those who use wheelchairs, and general medical supplies, Semingson says.

Hurford says he donated items to the Semingsons "multiple times. It's a good cause. I preferred to give to somebody who's going over there and providing help directly." He says he also donated items for other causes before selling Pacific Northwest Medical Supply last year.

The Semingsons stuffed a half-dozen cardboard boxes, each big enough to hold an office chair, with the donated items. They wrote "medical supplies" on the boxes and checked them on the plane when they traveled. Hurford had given them so many things they couldn't take them all in one trip.

"Shipping is expensive," Semingson says. "The airlines were great. They would do their security checks on the boxes, and send them through" at no charge.

Sometimes the Semingsons have air-mailed from here smaller items in particular need, such as pulse oximeters, which are used to measure the oxygen intake of those who might need help in breathing. It takes weeks for the mailed items to arrive, Semingson says. Some other donors, including Direct Supply, an institutional medical supplies business in Milwaukee, have donated items, he says.

The World Health Organization works with the hospital, but the hospital's needs continue, Semingson says. Last year, when the Semingsons stepped out of the hospital room of a friend's mother whom they'd visited, three or four chickens walked down a hospital hallway.

"We've done a lot of work with the hospital on their geriatric center," Semingson says. In 2008, Alice Semingson, 53, an RN who established a copyrighted care program for Alzheimer's disease victims, conducted lectures and training sessions on elder care, dementia, and wound care for the hospital's nursing program and geriatric unit, a nurse practitioner program, and public health nurses. She has done such sessions each year since, and in 2011 will do training sessions for the hospital and the University of the South Pacific.

Alice Semingson, who has extensive experience in health-care management in retirement settings, founded Ash Geriatric Services to train caregivers and also does litigation consulting, sometimes reviewing medical records to give plaintiffs or defendants an opinion on a case and serving as an expert witness. Ron Semingson, whose experience is in operations, advises on operational procedures, guidelines, and policy, and helps new facilities with procedures, processes, and licensing. He, too, serves as an expert witness at times. He's been in the retirement center business since about 1970, and remembers when care for Medicaid patients was reimbursed at $6.06 a day.

As the Semingsons have returned to the Cook Islands each year, their visits have borne fruit:

•When they dined at a restaurant in Rarotonga about a decade ago, the proprietor introduced them to Donna Smith, a trained occupational therapist. Smith invited them to Te Uki Ou School, a private school with about 60 students, a dozen of whom were disabled. Some of the disabled children had outgrown wheelchairs that also were inadequate to support their spinal columns. Smith was assessing their needs for new wheelchairs for NZ Aid, a New Zealand aid organization that in a survey of the Cook Islands had found the need for up to 300 wheelchairs.

Ron Semingson told a fellow airline passenger about that during one of the Semingsons' return flights from the Cook Islands. "She said, 'I have three wheelchairs in my garage. You can have them.' I told her to contact New Zealand Air to inquire about shipping the wheelchairs to the Cook Islands. She did. New Zealand Air made arrangements to ship them." Now, the Semingsons are working with a San Francisco company that's evaluating how to deliver new wheelchairs to the islands.

The Semingsons helped set up a foundation at Te Uki Ou School to raise money to pay a $200 fee required each time the school seeks to license a teacher's aide.

Smith, who has become a friend, has learned of families who are caring for dementia sufferers who live with them, and Alice Semingson has visited the families to advise them how to care for relatives with Alzheimer's disease, Ron Semingson says.

•The Semingsons visited the island of Atui, where some 300 people live, because Smith said there were numerous dementia cases there. They met with a man who believed it was his fault that his wife, who had been a teacher, had contracted dementia and acted strangely. The Semingsons assured him that his wife's dementia was the result of a disease.

Another family, whose son Smith had assessed for a wheelchair, had killed a goat, a chicken, and a pig, cooked the meat, and prepared salads for what Semingson called "a beautiful layout" to honor the Semingsons and Smith.

"They had a social worker. We gave her some training, to make these peoples' lives a little better," Semingson says. Atui's small hospital was painted and clean, he says. "They had three nurses, but no patients. They were thinking about converting it over for Alzheimer's patients" and sought the Semingsons advice on how to do that.

Three years later, the transition is still under discussion, he says. Local politics take paramount importance, and change is neither easy nor quick, Semingson says. For example, one island is populated only by 50 people, all of whom have the surname Marsters. Yet, the island is trying to replace its representative to Parliament, saying he is from a certain wing of the family and shouldn't represent all of the Marsters.

•Because the Cook Islands has no elder-care industry, it has no regulations for such an industry, and the minister of health has contacted the Semingsons to talk with them about regulation. The house of Parliament, really not much more than a ranch house, is next door to the beach home on Nikoa Lagoon where the Semingsons always have stayed, 60 feet from the edge of the water.

The Parliament includes just 13 members, and the atmosphere is informal, as it is in the prime minister's office, Semingson says, adding, "You can walk in and talk to him."

Yet, the Deer Park couple's relationships with the residents of the Cook Islands have resulted from "small town stuff," or face-to-face conversations and friendships, rather than contacts with officials, Semingson says.

Not long ago a man contacted Donna Smith to say he would be interested in building a new structure for the elder center. Semingson says the center could use such a building.

Latest News

Related Articles