Palouse wind-turbine farm eyed

Boston company plans $170 million project near Oakesdale

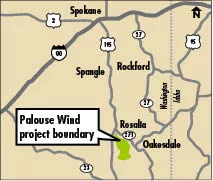

A Boston company says it expects to receive a conditional-use permit from Whitman County in the second quarter of 2011 to construct a $170 million wind-turbine farm about seven miles west of Oakesdale, Wash.

The company, First Wind LLC, says it plans to call for bids on the project and a related four-mile power line late next year or early in 2012, and adds that it would take six months to complete construction.

First Wind plans to erect about 50 wind turbines in wheat fields along Naff Ridge, which is roughly one mile east of U.S. 195, to capture a prevailing southwest wind, says Ben Fairbanks, director of business development in First Wind's west region. The turbines, which together could generate up to 100 megawatts of power at any one time, likely would produce an average amount of electricity sufficient to serve 25,000 homes, he says. Each of the turbines would produce 2 to 2.5 megawatts of power, depending on the models that are chosen, and would be mounted on towers that would be up to 300 feet tall and, including the tips of their blades, would reach 350 to 450 feet in the air.

The company would build the four-mile, 230-kilovolt electrical line needed to carry power from its wind farm to Avista Utilities' Shawnee-Benewah transmission line, which Avista upgraded not long ago, Fairbanks says. The Avista line would carry the juice to distribution points.

"We're working on our interconnection agreement with Avista," Fairbanks says. First Wind also will negotiate a power purchase agreement with a utility that would buy the electricity from its wind-turbine farm, which it's calling the Palouse Wind project. Avista, which has suspended its own wind-turbine project near Reardan, Wash., could be "a natural partner" for a power purchase agreement, he says.

"This is, if not the best wind construction site in Avista's territory, a site that's constructable, close to transmission, and in a county that's interested in jobs," he says. The power will be sold through competitive bidding, but if Avista were to buy power from a source outside of its service territory, it's likely that power would be more expensive, Fairbanks says. He says the electricity would help a utility meet Washington state's requirements for obtaining electricity from renewable sources.

First Wind, which has eight operating wind-turbine farms in Maine, New York state, Hawaii, and Utah and is constructing four more, launched operations in 2002 with about 13 people, says Fairbanks, a Yakima, Wash., native whose office is in Portland. He says First Wind, which originally was named UPC Wind, grew quickly, and now has 250 employees and offices around the country.

The company went from owning three wind farms to owning eight during "basically the worst credit crisis this country has seen in a lot of years," Fairbanks says. During that time, it raised more than $1 billion for projects, and it sees its ability to raise capital as its strong suit, he says.

The company is in the business of developing, owning, and operating wind-turbine generating facilities rather than developing and selling them, Fairbanks says. "We're not out there to flip projects," he says.

The company has filed paperwork with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission to go public through an initial public offering that likely will occur in the coming months, he says.

"The American people are interested in investing in home-grown energy," he says. "We'll be the only American-owned publicly traded wind energy company. We think we have a place in that market."

To evaluate the Naff Ridge site, First Wind erected 60-foot-tall meteorological towers, which have weather stations atop them that record wind speed, Fairbanks says.

"You need at least a year's worth of wind data to be bankable" when seeking financing to build a wind-turbine farm, he says. The company's analysis of the wind data it recorded was validated by a third-party consultant and correlated with long-term weather records at the Spokane and Pullman airports, he says. Wind-turbine vendors evaluate the data to determine what turbines would be suitable for a particular area and also to determine warranties, he says.

"There's a lot of science," but it's necessary, Fairbanks says. "No one is going to give you $170 million to build something just because you say it's windy."

First Wind has met with county officials, local residents, and other stakeholders, and the Whitman County Commission has adopted a wind energy ordinance after studying similar laws enacted in other Washington counties, he says.

First Wind has secured from 15 farmers long-term rights to sites where it would erect its wind turbines, he says. A map in the county courthouse in Colfax shows farms in Whitman County that have been in the same families for 100 years, he says, and adds, "Wind power is an opportunity for some of these farmers to keep doing what they love."

When they begin receiving revenue from their wind-turbine agreements, "I don't think any of these farmers are going to retire," Fairbanks says. Rather, he says, "I think they'd like to buy a new tractor, and not be squeezed as much when crop prices go down." The farmers, he says, see the wind turbines as "another way to harvest another crop on their land—the wind." They lose the use of about 2 acres of land for each turbine that's erected in their fields, but each turbine will generate about 100 times as much revenue as an agricultural crop would, he says. Farmers typically continue to grow crops around the wind-turbine sites.

CH2M Hill's Portland office is preparing an environmental impact statement on the project, with help from the engineering firm's Spokane office, and a draft of the EIS is scheduled to be done either late this month or early next month, Fairbanks says.

Jon Yoder, a Washington State University associate professor of economic sciences, has done a study on the economic impact of the project, and that study is about ready to be released, he adds.

"We're pre-qualifying local contractors" and running down local sources of such things as gravel and other needed materials and items, he says. He adds, "Spokane County will benefit from these projects" because it's so near the site, and businesses in Spokane County will supply many items for the project.

First Wind has rented offices in a business incubator in Oakesdale, and the Spokane office of Gallatin Public Affairs, a consulting firm, is staffing those offices for First Wind part time, Fairbanks says.

During construction, the project will employ an estimated 66 workers to erect the wind turbines and build roads and related facilities, he says.

"The bulk of the cost is in the turbines," Fairbanks says.

Thanks to an estimated $26 million in increased spending in the county, another 94 people will have jobs in supplying concrete, fencing, and gravel; trucking and vehicle repair; road maintenance; engineering and environmental consulting; lodging and food service; title, escrow, and legal services; and tourism, First Wind says.

When the project is done, First Wind will employ eight people permanently, including "windsmiths," who maintain and repair wind turbines, and administration and management personnel, at an operations and maintenance office in Oakesdale, Fairbanks says. The wind-turbine farm's activities will result in sufficient additional spending in the county to provide another 10 permanent jobs, he says.

Inevitably in such a project, questions come up about how the wind turbines will alter views, Fairbanks says.

"Some people think the turbines are cool, modern, enhance things, and put people to work. I've worked in Wyoming, where everybody complains about the wind," but their attitudes change when they see wind turbines generating power, he says.

"Some people just don't want the viewshed to be disturbed," he says. Yet, he adds, "The farmers tell us, 'The Palouse is scenic, but this is the most industrial ground in the state of Washington; we've been farming it for 100 years.'"

There's little wildlife in the project area, no wetlands, and no streams, and because the land is heavily in crops, "you're hard-pressed to find a tree," Fairbanks says. First Wind invited the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Washington state Department of Fish and Wildlife to visit the project area, and the company followed the latter agency's wind-energy guidelines in its planning, he says. The company has done what are called "avian point counts," in which biologists stand for 20 minutes at a time once a week for a year to observe bird life, Fairbanks says. Also, First Wind did a flyover of the project area to count raptor nests. The project did not require habitat mitigation or mitigation for effects on agriculture, he says. The company also has done archaeological studies, visual simulations of the wind turbines, and transportation studies.

Expansion of the project later is unlikely, Fairbanks says.

"What makes this area unique is the orientation of a few ridgelines that elevates the hills above the bumpy, 'oceanic' nature of the Palouse," he says. It's possible to service the project as planned with a single, relatively straight road, but that wouldn't be the case if the project were expanded, Fairbanks says.

The company has put up meteorological towers at other sites in Spokane and Adams counties, and some property owners and managers are putting up their own such towers to gather information on wind speeds on their lands for possible development of wind turbines, Fairbanks says. Yet, he says, Avista's upgrading of its transmission line near the project area was the biggest factor in First Wind's decision to develop the project.

Related Articles

_c.webp?t=1763626051)

_web.webp?t=1764835652)