Home » New HIV medicines are making for better lives

New HIV medicines are making for better lives

Spokane doctors say new medications are less toxic, more effective

October 21, 2010

Due to advances in medicine and the administration of more personalized treatments, people with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) aren't just able to live longer: Many are able to live what some practitioners here describe as normal lives.

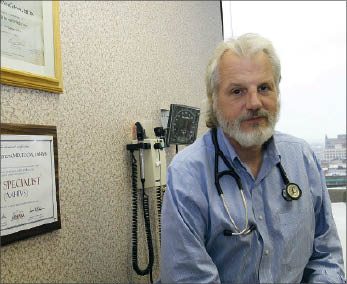

One of those physicians, Dr. Daniel Coulston, an HIV specialist who practices critical medicine through Deaconess Medical Center, says he has been treating patients with HIV or acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) for almost 30 years. Coulston says he currently is treating about 400 HIV patients throughout Eastern Washington, Idaho, and Montana.

He says that a patient undergoing HIV treatment is usually virologically suppressed—meaning that the virus is under control—and his or her immune system is still functioning, even though it's in a compromised state.

"I have patients who work in health care, construction, and professional careers. They have families and work," he says.

Coulston says he has seen a lot change in how HIV is treated, especially since one of the focuses of his practice is testing new HIV drugs on patients who may have built up a resistance to the drugs currently available on the market.

About two years ago, Coulston tested a new drug on 50 of his patients who had built up multi-drug resistances. He says if they hadn't had access to the new medication, they probably would have died from their condition.

"It was that bad," he says. "All of these patients were failing their treatments, but about a month or so into the trial, they started improving and turned around."

Coulston says he believes his practice is the only HIV clinic in Eastern Washington that does research on new HIV medications. The clinic has a certified clinical research coordinator, Melodie Dowdy, who oversees the trials.

"Patients here have access to a lot of these drugs years before they are actually available on the market," he says. "The drugs we are testing are way ahead of the current drugs that are commercially available."

Currently, about 28 approved drugs have been developed to treat HIV, and the medications fall into five different classes, based on how they work on a cellular level, Coulston says.

Because each class of drug affects the virus' ability to take over a cell in different ways, some can be combined, based on the patient and the chemical interactions of the drugs, he says.

Dowdy says that not only have the majority of HIV drugs become more effective, but they also now have a lower level of toxicity and fewer side effects, and patients can take fewer pills than in the past.

The medical technology of one of these drugs, marketed as Selzentry and classified as an entry inhibitor because it blocks HIV from entering a cell, was discovered because scientists found a mutation in Northern Europeans, Coulston says.

That mutation is thought to have occurred in Europe during the bubonic plague of the 1500s, and resulted in the deletion of a specific cell receptor to which HIV attaches and uses to enter a cell, he says.

"When we learned this, we were able to develop a drug that blocked this specific receptor. Now, this knowledge is being applied to other diseases as well," he says.

Coulston says that other advances in medicine in the last decade or so also have changed the way HIV is viewed by medicine. He says it is now viewed as more of a chronic disease than a terminal illness.

"HIV is not what's going to kill you," he says. "Most people with HIV die of other complications like Hepatitis C."

Yet, even with the major advancements in HIV treatments, some sufferers of the disease are more negatively affected by their condition than others and are unable to hold a job or function well in their daily activities, says Debbie Stimpson, a nurse practitioner in the HIV clinic at Internal Medicine Residency Spokane, a program here that trains medical school graduates.

"Depending on what stage someone is in with the disease, they may have an increase of fatigue or a range other symptoms," Stimpson says.

The main difference between someone with AIDS and a person who is classified as HIV positive is that the number of a specific type of cells in the immune system—CD4 cells—has dropped below a count of about 200 cells in a pea-sized drop of blood; or they have developed what is called an opportunistic infection as a result of their weakened immune system.

Someone who is HIV positive but has not developed AIDS usually has a CD4 count of about 300-500, Coulston says. The fewer the functioning CD4 cells in the blood, the weaker the immune system.

One hot-button question that's been debated among HIV specialists for years now is when to start treating a patient with the disease, he says, adding that the determination is based on the patient's CD4 cell count.

"The trend is to start earlier than later," he says, but adds that even after a person starts treatment, their immune system will never fully recover to the same level of function it was at before the onset of HIV.

Coulston says that most doctors begin treating a patient once their CD4 count has dropped to below 350, but some doctors will recommend treatment at a CD4 of around 500.

"The longer you wait, the more complications with medication and treatment there can be. It also takes the immune system longer to get better," he says.

According to the Washington state Department of Health's latest available quarterly HIV Surveillance Report, there were an estimated 531 new cases of HIV diagnosed last year across the state, 17 of which were in Spokane County. The Spokane County number is down by nine cases from 2008, and the county has averaged about 25 new cases a year over the last six years.

In 12 counties that make up the majority of Eastern Washington, including Spokane County, there were about 26 new cases of HIV reported in 2009, the report says.

In all, there currently are about 415 people with HIV living in Spokane County, which includes both those who are HIV positive and those whose disease has progressed to the point they've been diagnosed with AIDS, the report says.

"The number of new cases every year is at a steady rate," Stimpson says. "The death rate has dropped off, so the number of HIV patients is increasing."

Yet, even with an increasing number of HIV patients living in the community, Stimpson says she believes there's an adequate number of specialists in the Spokane area to treat them.

"There is not a shortage of providers here, but a shortage of access to them and a longer wait to see them," she says.

Overall, about 10,500 people are living with HIV or AIDS in Washington state, and since 1982, about 5,100 people in Washington have died because of the disease, the state Department of Health says.

Because of the recent advances in HIV treatment methods, more people are living with HIV or AIDS in Washington state and Spokane County than ever before, says Katie Coker, executive director of the Spokane AIDS Network, a nonprofit that has been providing services to people living with HIV in the Spokane area since 1985.

The network provides medical case management and advocacy services to about 200 clients in the Spokane area, including an HIV prevention program, free HIV testing, referrals to HIV specialists, assistance with insurance paperwork, and medical nutritional therapy, she says.

Even though HIV drugs have improved in recent years, Coker says she has noticed some complacency in regard to risky behaviors that can lead to HIV infection. "Some people have the impression that HIV is not really a serious disease anymore," she says.

When asked if it's possible that a cure for HIV may be discovered in the near future, Coulston says, "Is it possible? Yes. Do we have the technology? Yes, but we can't do it yet. Maybe in 10 to 20 years though."

Latest News

Related Articles