Tax planners here know that uncertainty abounds

As Congress takes break, many questions linger over expiring provisions

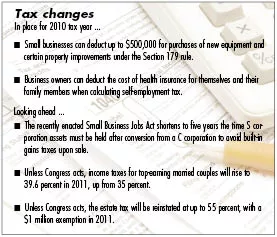

With Congress in recess until after the November elections, tax planners here say they're facing more uncertainty than usual before tax season, although the recently enacted Small Business Jobs Act contains some tax incentives that business owners can plan for.

Andrew McDirmid, a tax partner at the Spokane-based accounting firm McDirmid, Mikkelsen & Secrest PS, says Congress left behind huge unanswered questions when it broke for recess recently, leaving many tax issues unresolved.

"I don't think we've ever seen this much uncertainty with less than three months left in the year," McDirmid says. "It's going to make December very busy."

If Congress allows the so-called Bush tax cuts to expire, the top rate likely will return to 39.6 percent, up from the current top rate of 35 percent, he says.

"There's kind of a push now to accelerate income in 2010," McDirmid says. "That's not always easy to do, and few people can do it." It's done by arranging to receive payment of income before the year ends so it could be taxed at a lower rate.

Another issue clients are facing is whether to defer making tax-deductible expenditures until after 2010 so they can deduct the expenses from 2011 revenue, when it's presumed tax rates might be higher, he says.

"People are holding off on fixed-asset expenses if they can to push out the deduction until 2011 or until they have some clarity with the tax rates," McDirmid says. Fixed-asset expenses involve such big-ticket items as property, plant, and equipment.

Chris Hesse, director of taxation at Spokane-based LeMaster Daniels PLLC, says the Small Business Jobs Act, which president Obama signed into law last month, contains some tax breaks to encourage private economic growth.

The act expands for 2011 the Section 179 expense deduction that allows business owners to reduce their tax liability by deducting as an expense the full price of equipment they have bought during the year. The act allows up to a $500,000 first-year write-off for equipment and covers certain property improvements.

"That means for the majority of business owners, they could write off all business equipment purchases in the year it's acquired," Hesse says.

Taxpayers, however, would forgo depreciation that would reduce taxable income in later years, which could become an issue if tax rates go up, Hesse says.

The act also reduces to five years the minimum period for which the owners of S corporations that have been converted from C corporations must own the companies and their assets for the companies to escape taxation on gains realized when either the companies or their assets are sold.

S corporations that change hands or sell appreciated assets during the holding period are subject to a 35 percent tax on what are called built-in gains. Businesses that are subject to built-in gains taxes must pay them in their tax returns for the year in which the sale occurs, Hesse says.

The shorter holding period allows the corporations to avoid taxes on built-in gains when a sale occurs after five years. The holding period had been set at seven years for businesses and assets sold in 2009 and 2010, and it was set at 10 years before 2009.

C corporations pay taxes on their earnings. When a C corporation starts to make a sizable profit, or if the stockholders ultimately plan to sell the company, it's often advantageous to convert the company into an S corporation, in which shareholders, rather than the company, are liable for taxes on profits, Hesse says.

Also for this year, the act allows business owners to deduct the cost of health insurance for themselves and family members when calculating self-employment taxable income.

Next year, tighter reporting restrictions for independent contractors will kick in. Starting in 2011, any company that buys more than $600 in goods and services from a vendor must submit a 1099 form, which is used to report a variety of payments that would be income.

Hesse says Congress expanded the definition of businesses required to fill out 1099 forms, and reporting requirements will include the buying of services, inventory, and equipment.

"Ultimately, I think that provision will be repealed, but it's in the law right now," Hesse says.

David Green, a tax partner at the Spokane office of Seattle-based Moss Adams LP, says the goal of the 1099 requirement is to raise revenue to pay for other tax breaks by tracking down unreported income.

"Every business is going to get slammed pretty hard if Congress doesn't fix it," he says. "Otherwise, Congress will have to figure out whether the pain is worth the revenue coming in."

Green says the uncertainty about higher taxes has turned tax planning on its head. Usually, taxpayers want to take the maximum deductions allowed as soon as they can, he says.

"If, however, tax rates are going to be higher in 2011, you might want to accelerate income in 2010 and push out deductions until 2011 when they are going to be worth more," he says.

High-income earners, especially those with annual income higher than $375,000, likely would be most affected by tax increases. Currently, the top income tax rate for that income bracket, as mentioned earlier, is 35 percent.

If Congress does nothing and tax rates revert to pre-Bush levels, the top rate could exceed 42 percent, Green asserts.

He calculates that rate by taking the highest proposed individual tax rate of 39.6 percent and adding more than 1 percentage point for the potential loss of itemized deductions and another 2 percentage points for the potential phase-out of some personal exemptions.

"Business owners easily could be among folks in that bracket," he says.

Green says he's concerned that gridlock will continue in Congress after the November elections and, as a result, tax rates might automatically return to their pre-Bush rates. "If members of Congress can't agree before the election, it doesn't make me think they will come to some agreement afterward," he says.

Also, if gridlock continues, the federal estate tax will return, at a rate of up to 55 percent on inherited assets that have a value in excess of $1 million, he says.

The estate tax, which in 2009 was 45 percent for estates valued at more than $3.5 million, expired after last year, leaving no estate tax in effect for 2010. Unless Congress takes action, however, the estate tax is scheduled to return next year, though at the higher rate and with the lower exemption.

"Someone who might have an estate worth $5 million and who is married and has done everything right (in terms of planning) might have $3 million that's subject to tax," he says. "If something happens, all of a sudden they have to pony up $1.5 million plus Washington state estate tax."

Green says some of the income-tax concerns might amount to "nickel-and-dime stuff" compared with the estate tax.

"The estate tax is the scary part," he says. "With income tax, the increase on $1 million in taxable income might be $40,000, but the estate tax, that's real money."

He says people who might be subject to the estate tax should review their estate planning with a lawyer or accountant who specializes in such work.

Hesse says he expects Congress will reset the estate tax at 45 percent, with an exemption of $3.5 million, although some Republicans have talked about holding out for a $5 million exemption.

It's unlikely that Congress will make the estate tax retroactive to include 2010, he says.

"There's no estate tax out there now," he says. "The U.S. Supreme Court hasn't ruled on whether you can impose a tax retroactively. Heirs of at least five billionaires he can think of who died in 2010 would be willing to spend a lot on legal fees to take that issue as high as they could" in the court system.

Congress hasn't come up with a permanent fix to a problem with the alternative minimum tax (AMT), which because it hasn't been indexed for inflation for years is applying to an increasing number of middle-income taxpayers. McDirmid says he's expecting a temporary patch to the AMT, which is intended to prevent wealthy people from taking unfair advantage of loopholes to avoid paying income taxes, for 2010 at least.

Congress has been adjusting an exemption to the AMT on a year-by-year basis for years, and McDirmid says, "Going back to 2001, anytime we rough out a tax projection, we have to make a disclaimer that we think there is going to be a patch for this. Many people will be subject to the AMT (for 2010) if Congress doesn't approve some kind of cost-of-living adjustment to the 2009 rate."

Another unanswered tax question is whether older taxpayers will be allowed to donate to charity up to $100,000 tax free from an individual retirement account, he says. A provision that allowed such contributions expired at the end of last year, but could be reinstated retroactively for 2010, McDirmid says.

"That's a big deduction, he says. " A lot of our clients are holding off on making charitable contributions until they have clarity on that."

People who give as little as $2,000 from an IRA account should check to see whether the donation would count as income and affect their Social Security benefits, he says.

Related Articles

_c.webp?t=1763626051)

_web.webp?t=1764835652)