Home » Cleanup plan dulls mining's glow

Cleanup plan dulls mining's glow

With metals outlook good, new EPA plan triggers worry

November 4, 2010

North Idaho's Silver Valley is poised for renewed prosperity in mining—and the highly paid jobs that industry brings—but the most recent proposal by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to clean up historic mining pollution there could jeopardize that potential, industry advocates contend.

Last summer, in the next step in a long-running Superfund cleanup of heavy metals in the valley, the EPA suggested a plan that would greatly expand the cleanup and would take at least several more decades and cost an estimated $1.3 billion. The EPA is taking public comment on the plan until Nov. 23, and expects to decide by next spring whether to implement it.

Mining executives and others in the Silver Valley, however, argue that the plan goes too far and takes the wrong approach. They also worry that such a massive cleanup would take precedence over all other development in the valley, jeopardizing capital investment by mining companies and job growth at a time when the market prospects for the silver, lead, and zinc there suggest another mining boom in the district.

"The Silver Valley is blessed with significant mineral resources, that's for sure," says Mark Compton, government affairs manager for the Spokane-based Northwest Mining Association. "But if you are investing in mining, it's tough to put your money there because of the uncertainty."

For their part, EPA officials argue that the agency will work closely with mining companies and others to ensure that economic development continues during the cleanup.

"EPA has been doing cleanup in the Coeur d'Alene Basin for more than 20 years, and has a long track record working with property owners, including the business community, to address their specific concerns about how cleanup could affect the use of their property," says Cami Grandinetti, a Seattle-based unit manager in the EPA Superfund program. "In many instances, EPA's cleanup work has facilitated economic development, such as helping to create cleanup jobs or providing financial institutions with cleanup documentation in support of a residential loan application."

Some big potential mining projects are looming.

Last week Coeur d'Alene-based Hecla Mining Co. said it expects to make a decision by mid-2011 on whether to go ahead with a $150 million to $200 million project to construct a new internal shaft at its Lucky Friday Mine, near Mullan. Hecla says the project would open up veins that would double the mine's annual silver output and greatly extend its productive life. The Lucky Friday currently employs roughly 300 people and miners there earn $80,000 to $100,000 a year, Hecla says.

Meanwhile, U.S. Silver Corp., the Toronto-based operator of the Galena mine and owner of the nearby Coeur and Calladay properties, is raising money to try to reopen the shuttered Coeur mine nearby. The company already employs about 230 people at its Galena mine, which is located near Wallace.

Last May, Dallas-based Silver Opportunity Partners LLC bought the assets of Coeur d'Alene-based Sterling Mining Co., which owned the historic Sunshine Mine near Kellogg. The new owner hasn't disclosed yet what it plans to do with the mine. Says Laura Skaer, executive director of the mining association, "I don't know what their plans are, but they didn't buy that mine as a Christmas ornament."

Although mining employment is down markedly from the Silver Valley's boom years, the industry currently employs more than 500 workers in Shoshone County. That's a fraction of the more than 2,400 jobs the industry provided back in 1980, the last time silver was selling at prices above $20 an ounce, but an improvement over the low of about 290 jobs in 2003, when silver prices were below $5 an ounce.

Miners make far more than those in most other occupations there. Alivia Body, regional economist for the Idaho state Department of Labor, says the average wage for all industries in Shoshone County is about $31,600 a year, while the average wage in the mining industry is about $60,500. Mining accounts for about 11 percent of the county's employment, Body says.

Mining is a staple of the valley, says Charles Wardwell, an economic development specialist with the Silver Valley Economic Development Corporation, based in Wallace.

"Mining provides very good jobs with very good benefits, and they do it in a very environmentally friendly way," Wardwell says. "This isn't the 30-year-ago scenario," he says of past mining practices now seen as environmentally irresponsible.

Phillips S. Baker Jr., Hecla's president and CEO, says he has renewed optimism about mining in the valley, but fears the pall of a 50- to 90-year environmental cleanup plan would cause the valley to miss out on prosperity other mining districts in the world are experiencing given current prices and demand for metals.

"There is a boom in mining all over the world, but not here. Why?" asks Baker.

Hecla, which has been doing extensive exploration and analysis of the land it controls at and near the Lucky Friday, is in a good position to invest in the valley. Last week, it reported third-quarter financial results that included record revenue. The company has generated $115 million in cash flow this year and now has $217 million in cash and equivalents on hand.

Others, however, will struggle to secure financing as long as the uncertainty of the EPA cleanup remains, observers contend.

"When you're talking about a 50-year or more designation, it creates a lot of uncertainty," says the mining association's Compton.

He adds, "The fear is that with the EPA focus on the cleanup if they perceive a project will interfere with that focus, then what's going to happen to that project?"

Skaer says she's hearing from mining companies that are having trouble raising capital to do exploration or mining projects in the valley because of the "threat of this Superfund project."

She says that given the high demand for silver, lead, zinc, and copper, "I would have expected to see more exploration activity taking place" in the valley. "I think it's the EPA's presence that dampens that."

The Superfund plan aside, "I've never seen (potential) like this before," Skaer says. She adds, "The current prices are a help, but given what we know about the valley is what is promising, and most of the discoveries that are taking place today worldwide are taking place in old mining districts."

Currently, silver is selling for about $24 an ounce, compared with less than $10 an ounce five years ago. Meanwhile, lead prices have roughly tripled and zinc is up about 50 percent in that time frame.

Says, Skaer, "As the third world continues to develop, we're going to have to become more self-reliant on metals in the U.S."

The EPA plan

The EPA's most recent record of decision, or cleanup plan, for what it calls the Coeur d'Alene Basin was issued in 2002 and focused mostly on threats to human health, specifically cleaning up soil in yards contaminated by heavy metals. The cost of that interim plan was about $360 million, in 1999 dollars.

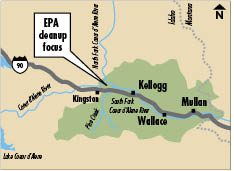

The Silver Valley, which generally stretches along Interstate 90 from about Kingston to the Montana border, has been mined for more than a century, and at times has been one of the world's top producers of silver, lead, and zinc. As a result of past mining practices, the valley has been contaminated with elevated concentrations of lead, zinc, cadmium, arsenic and other metals, the EPA says. The cleanup area, known as the Bunker Hill Superfund Site, named for the Bunker Hill Mine, near Kellogg, was placed on the national priorities list in 1983.

The EPA says that since 2002, it has learned enough additionally about the mining waste in the basin to necessitate an expanded plan, and in July it recommended an amendment to the 2002 record of decision. The plan focuses on what the EPA calls the Upper Basin, or the area of the watershed that feeds the South Fork of the Coeur d'Alene River.

The new, $1.34 billion proposal includes a host of actions, ranging from extensive excavation of waste rock, tailings, and flood-plain sediments, to collection and treatment of groundwater.

Hecla officials have analyzed the plan and have proposed alternatives to the EPA plan, which it says includes creating five to six new repositories for contaminated rock and soil, installation of plastic stream liner beneath one tributary, installation of a pipeline to transport groundwater, and expansion of a groundwater treatment plant in Kellogg that would be twice the size of the one that serves the city of Boise.

Hecla officials say they don't dispute the need for further cleanup in the basin, but they contend that the proposed plan's extensive scope is unnecessary, some of its proposed actions are ill-conceived, and the expected cost is far too high.

Adds Compton, "Everyone in the industry will acknowledge that there is still cleanup to be done, but what they have proposed isn't workable or necessary."

As for specifics in the plan, Hecla says that diverting groundwater flows into 59 miles of piping to a central treatment plant would reduce flows dramatically in the South Fork and some of its tributaries. Canyon Creek, for instance, would lose more than half of its flow and parts of the South Fork would lose a quarter to more than a third of its flow, Hecla estimates.

Instead, Hecla recommends that any new plan should seek to control pollution at its source sites, treating groundwater there with smaller facilities.

The EPA's Grandinetti, however, says, "Contrary to some claims, groundwater collection and treatment will not 'dry up' the creeks and rivers. EPA has estimated that groundwater collection would remove less than 10 percent of the stream flow during 'low flow' conditions and less than 4 percent of the stream flow during average conditions."

Overall, Hecla suggests a 10-year plan that would cost between $150 million and $175 million and would include more flood-control efforts than the EPA's plan. It contends that having a 10-year plan, would give private interests a more reasonable planning horizon for investments in the valley they might pursue.

Contends Grandinetti, "Hecla's plan is faster and less expensive because they propose to do less cleanup than EPA in the Upper Basin. The Hecla plan would not be a final cleanup and would increase the community's uncertainty about what it would take to complete Superfund cleanup in the Upper Basin."

Hecla is still on the hook as a "responsible party" in the EPA's cleanup efforts in the basin, although the amount it will pay won't be known until ongoing litigation with the federal government and the Coeur d'Alene Tribe of Indians is resolved. Last year, Tucson, Ariz.-based Asarco Inc., once a big player in Silver Valley mining, settled with the government by agreeing to provide $482 million toward cleanup costs.

Latest News

Related Articles