Program rolls out here to put defibrillators in high schools

Children's Hospital effort aims to help youths survive incidents of cardiac arrest

Sacred Heart Children's Hospital has launched a program to install automated external defibrillators in Inland Northwest high schools, triggered partly by what it says has been a recent spike in adolescent deaths due to cardiac arrest.

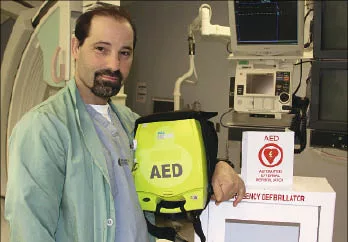

"It is Sacred Heart's goal to include all high schools that wish to be involved in this program," says Ryan Schaefer, a registered nurse and the electrophysiology coordinator for Providence Sacred Heart Medical Center & Children's Hospital.

In that capacity, he works under electrophysiologists, or cardiologists who specialize in the electrical functions of the heart, and coordinates the medical center's electrophysiology program, which treats arrhythmias of the heart and installs pacemakers and internal defibrillators.

Defibrillators are electronic devices that apply an electric shock to restore the rhythm of a fibrillating heart, which is undergoing rapid contractions of muscle fibers resulting in a lack of synchronism between heartbeat and pulse. It can be fatal. Pacemakers help regulate heartbeat.

The Sacred Heart Children's Foundation has provided a $110,000 grant to fund the installation of automated external defibrillators, or AEDs, at high schools. Schaefer says that money likely will be exhausted in a matter of months, though, so the program will be exploring other sources of funding to pay for future installations.

"I think it's a program that could go on for quite some time," he says.

The Sacred Heart program is affiliated with Project Adam, a Wisconsin-based nonprofit started in 1999 by the parents and friends of 17-year-old Adam Lemel, who died of sudden cardiac arrest. Project Adam's mission is to serve young people through education and deployment of life-saving programs that can help prevent such deaths. Affiliates of the nonprofit carry out that work largely through partnerships with school systems, partly because an estimated 20 percent of a community's residents are in or visit a school on any given day.

About 2,000 young people reportedly experience a sudden cardiac event each year, and national statistics for adults are seven times that rate, a Project Adam pamphlet says. In such cases, the heart must be defibrillated quickly because a person's chances of survival drop by 7 percent to 10 percent for each minute a normal heartbeat isn't restored.

Half or more of the high schools in Washington state don't have AEDs, however, and the urban areas of Spokane and Seattle are among the areas of the state where they're least available, Schaefer says. He attributes that partly to administrative red tape and liability-related concerns at some of the larger school districts.

"It's Sacred Heart's goal to overcome some of the barriers that have come up in previous attempts to place AEDs in high schools," he says, adding, "We've really taken it upon ourselves to get involved with a program like Adam and to customize it to Spokane to overcome these barriers."

Schaefer says, "We've been working on it for a solid six months with how we were going to implement it into the Spokane area. It's really a team effort within Sacred Heart. We are ready to start in kind of a staged, systematic way."

The first three devices were scheduled to be installed last week and this week at Northwest Christian Schools' Colbert campus and at high schools in Newport and Northport, Wash., he says. Also, he says, "I think we're hopeful it will be implemented into the Spokane school district system in a short period of time," and the program has made initial overtures to Central Valley School District.

Of awareness of the program, Schaefer says, "Essentially it's been through word of mouth that it's gotten out there," bolstered by three sudden cardiac arrest incidents in the Inland Northwest over about the last year.

One of those involved a Northwest Christian student athlete who was stricken and died a couple of months ago while warming up for a fun run, he says. The other two involved a Gonzaga University student playing intramural basketball who survived and an athletic director in Wilbur, Wash., who experienced sudden cardiac arrest while preparing to announce a volleyball game, had his heart stimulated with an AED, and survived, he says.

"Those three events have really springboarded our program" by stirring heightened interest in AEDs, Schaefer says. "Those events really hit home with people."

The AEDs that Sacred Heart will be installing are portable devices about the size of a small laptop computer and are stored, together with a sealed plastic bag containing the adhesive pads that attach to the patient, in a soft carrying bag with a handle.

The AED is kept in a clearly marked metal box that's installed on a wall at a quickly accessible spot in the school. The box isn't locked, but is designed—both for security and emergency-alert purposes—to emit a loud alarm when its hinged glass-fronted door is opened, Schaefer says.

Sacred Heart buys the AEDs from Chelmsford, Mass.-based manufacturer Zoll Medical Corp., and the cost of acquiring and installing them ranges from around $1,600 to $2,000 per school, Schaefer says.

No certification is required to use the devices, which provide voice and visual prompts when activated, but program criteria dictate that school systems should have at least one staff member per 100 students who is trained in AED use and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) techniques, he says. Most schools have plenty of people capable of using the equipment, but the Sacred Heart program will help provide training on an as-needed basis, he says.

One of the bigger challenges, Schaefer says, is "finding the champion within the school to help you gravitate in there. We do require a site coordinator, or site champion," at each school who can oversee the program there.

Schaefer doesn't foresee the Sacred Heart program winding down even after most of the interested high schools in the Inland Northwest have an AED installed.

"Each school ideally would have more than one to cover the whole campus," he says, so the goal of equipping schools to an ideal level likely will take quite a while to achieve.

Related Articles

_c.webp?t=1763626051)

_web.webp?t=1764835652)