Home » Developer, city are in water fight

Developer, city are in water fight

Rayner contends city agreed to pay for system in '06, challenges contrary ruling

August 11, 2011

Spokane businessman Pete Rayner says a plan this year to launch the long-envisioned Beacon Hill subdivision in northeast Spokane is stalled until he and the city resolve the issue of who pays for a water system.

Rayner asserts the city promised in 2006 to build and pay for a water reservoir tank system to serve Beacon Hill, a then-proposed adjacent development, and future growth. With that understanding, he says, he deeded 3 acres near the top of Beacon Hill to the city in 2008 so it could build water tanks there.

In late spring 2010, Beacon Hill Properties Spokane, which Rayner owns with Dave Baker, of Spokane, submitted plans to the city for a $20 million-plus first phase of the project with just over 300 residential units on 40 acres.

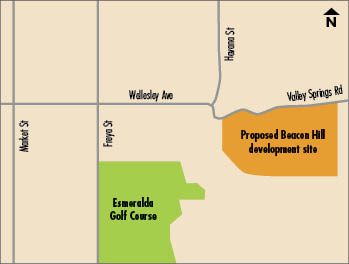

The property where the subdivision is to be developed is northeast of Esmeralda Golf Course, about a mile east of Market Street via Wellesley Avenue. The 300-unit first phase would be part of what's envisioned to be a 1,000-unit, 182-acre development that would be built over a number of years. Currently, the only development on Beacon Hill is the Beacon Hill Events Center, which Rayner owns with his daughter, Ellie Aaro.

In February, a city hearing examiner approved a preliminary plat and planned unit development for up to 304 single-family and multifamily residential units, with a condition that developers build an estimated $450,000 water booster station, until "a future date when a water reservoir tank is built and the booster pumps are upsized appropriately to provide service as a gravity system."

Now, Rayner is scheduled to appeal that specific condition before the Spokane City Council on Aug. 15. Rayner says he also is considering filing notice of intent to sue the city.

"The tanks aren't even in the city's plans now beyond the next six years," says Rayner. "They're burying us."

Beacon Hill's application proposes a subdivision with 71 single-family homes, and 69 townhouse units. An apartment complex with up to 164 units also would be located on 6 acres of land within the subdivision, he says.

"They agreed to provide me water in exchange for me giving them the land and me providing an access road," Rayner says. "We have to know that the city is going to honor its contract, or we can't proceed."

However, city spokesman Marlene Feist says the current Beacon Hill's preliminary plat and PUD approved by the city examiner, with conditions, is vastly different than what was under discussion preliminarily beginning in 2006.

"There were discussions in 2006 between the city and Mr. Rayner and a third party that was part of a development on Beacon Hill," she says. "They came to the city with an idea for development that would have up to 1,200 lots. We had a discussion about what type of water infrastructure would be needed for that size of development that the collective properties could have."

"What we're looking at today is a far different proposal of 141 lots and 304 dwelling units," she adds. "We were talking about the need for tanks then that doesn't make sense today."

She says the city has offered to convey the 3 acres of land back to Rayner.

"To initially serve the development that's envisioned now, our engineer says they need a water booster station," Feist says. "Mr. Rayner would pay for it upfront. We've agreed to reimburse him 50 percent of his cost for the water booster station building and yard piping."

The reimbursement would come as lots are sold and the charge to hook up to the city's water is paid, she says. "We'd reimburse him up to 50 percent out of those fees that are collected."

Rayner contends that a 2006 city water service plan for Beacon Hill called for the municipality to build a reservoir tank system to store water high up on Beacon Hill. He says the 3 acres he deeded to the city for these tanks is located about 300 feet above the already present North Hill water tank.

Rayner also asserts that the city in 2006 was eager to support his project and a separate plan for a development of apartments and townhouses on about 20 acres, called the Vistas at Beacon Hill. Rayner and Baker's 40 acres are to the southeast, uphill, and adjacent to the previously envisioned Vistas. The Vistas was proposed on land owned by the same people who ran an exotic animal farm known informally in Hillyard as the camel farm.

Rayner says the city wanted the farm—and its associated odors—to go away, which was part of the planning if the projects were built. However, the camel farm ceased operations in 2009, he says.

The end of that business effectively put the Vistas' option in limbo, he says, and Rayner asserts the city's interest in building a water system also evaporated. He says that for the past few years, he didn't receive any substantive response from the city about its plans to build a water tank system, and that communication really broke down after the 2007 retirement of Brad Blegen, then the city's water department director.

Rayner says Blegen drew up an 11-point plan in 2006 that outlined the city's responsibilities to bring water to Beacon Hill that Rayner and Blegen both signed. Rayner says he considers that document a contract.

The year 2007 is also when the city installed a 24-inch water line under Valley Springs Road, the water main that would serve Beacon Hill's lots, he says. Access to the Beacon Hill development would be via three streets that would connect to Valley Springs. The water main was to be served by a water booster station, to be constructed by the Vistas, but it was never built.

When asked if the city had any contracts for Beacon Hill's future water system with developers, Feist says Blegen had signed off on meeting notes, not a contract, after discussions with developers about the proposed projects. She adds that city department heads routinely do this to confirm that the notes from a meeting are accurate.

"Our legal opinion is they were not a contract, and the circumstances that existed then no longer exist," she says. "The third party is no longer a part of the discussion."

Feist contends that construction of a water tank system doesn't make financial sense today, based on the smaller number of homes proposed now, and also doesn't make sense from a safety standpoint. "If you have those tanks, you won't turn over the water quickly enough. You create stagnant water," she says.

She says the city would upsize the water pumps and plans to add tanks and other infrastructure as needed once development growth in the area exceeds the capacity to be served by a booster pump system.

For now, with the city as the water utility provider, it can't build sizable water infrastructure that essentially other ratepayers would be subsidizing, she says. "You're not allowed to have one group of ratepayers subsidizing the cost of benefit to another group of ratepayers."

Rayner says that the city in 2009 solicited bids for the Beacon Hill storage tanks as an element of several projects to be done, but that the tank project was later withdrawn.

"What we're fighting here today is an attitude of certain people in City Hall—not elected—who think any investment in Hillyard is wasted money," Rayner says. "They don't want to do this deal. The camel farm is gone, so they don't have any political reason to do anything."

He says with a developer paying all costs for a Beacon Hill water system, road construction, sewer system and other outside costs to build, "this project was never viable."

"The only way it was viable was that there was enough community benefit that the community helped pay a portion of the costs. Brad (Blegen) saw two reasons to support this: He didn't want to lose the water for future use and he saw a huge economic opportunity for the city of Spokane."

With Rayner's appeal of the city hearing examiner's decision to the City Council, council members have the authority to uphold it or change the conditions, Feist says.

Latest News

Related Articles

![Brad head shot[1] web](https://www.spokanejournal.com/ext/resources/2025/03/10/thumb/Brad-Head-Shot[1]_web.jpg?1741642753)