Inland Empire Paper uses algae-based technology to clean wastewater

IEP hopes it has found answer to phosphorus problem

In an ongoing effort to be able to meet future state requirements, Millwood-based Inland Empire Paper Co. is studying a new biological technology to reduce the amount of phosphorus in the wastewater it discharges into the Spokane River during its paper-making process.

For about two years, the 100-year-old paper mill has been working with Corvallis, Mont.-based AlgEvolve Inc., to study a wastewater treatment technology that company has developed using algae to remove phosphorus in wastewater from industrial processes and from municipal systems.

Doug Krapas, Inland Empire Paper's environmental manager, says the algae-based system is the 10th wastewater treatment technology Inland Empire Paper has tested at the mill during the last eight years. In that time, he says, the company has invested a total of about $9 million toward its effort to reduce levels of phosphorus and other nutrients in its wastewater.

So far, AlgEvolve's technology is showing promise other systems have failed to show.

Last week, the fourth test pilot operation concluded and that involved the treatment of about 1,000 gallons a day.

"Right now, other than this new technology, the only way to treat the water is through chemical treatment systems," Krapas says. "This is the first organic solution that is available on the market."

If the data collected during the recently completed, month-long testing session proves that AlgEvolve's technology was effective in removing phosphorus, a larger-scale test will follow to ensure the biological system could clean larger volumes of wastewater, Krapas says.

Inland Empire Paper produces about 3 million gallons of wastewater per day during its paper-making process, which turns recycled paper products and wood chips that are byproducts of the lumber industry into paper pulp.

Currently, the paper mill has two other treatment systems in place to remove waste material from that water, but neither of those systems is able to reduce phosphorus by the levels the state will require in eight more years, Krapas says.

The Washington state Department of Ecology plans to require both municipal and industrial entities discharging wastewater into bodies of water to reduce by more than 90 percent the amount of phosphorus in that water by the end of 2020.

One of the two current systems at the mill treats 1 million gallons of wastewater a day using a process called chemical precipitation, he says. That system, called the Trident HS and manufactured by Warrendale, Penn.-based Siemens Water Technologies, was installed in fall 2007, and Krapas says the mill continues to study its effectiveness.

During the chemical precipitation process, aluminum sulfate is added to the wastewater that then causes the water-soluble phosphorus to turn into a solid, which then can be filtered out of the water, he says.

The biggest issue with the Trident system is that the chemicals used in the process are costly and Inland Empire Paper is using about 1,800 pounds of them per day, he says. In addition, the solid waste that's filtered from the water currently doesn't have any reuse and must be disposed of.

"The problem is, what do you do with that chemical sludge?" he says. "There is no environmental reuse of chemical sludge. The organic solution provides an advantage over the chemical system."

Inland Empire Paper's secondary wastewater treatment system, called a moving bed biofilm reactor, also was improved between 2006 and 2009 to address levels of organic matter in its wastewater.

When organic matter is discharged via wastewater into a lake or river it's detrimental to fish and other parts of the ecosystem, because as that matter decomposes it depletes oxygen in the water, Krapas says.

The secondary treatment system uses bacteria to consume organic material in the water that's left over from the paper pulp-making process, and is somewhat similar in process to AlgEvolve's technology, Krapas says.

Kevin McGraw, operations manager and a co-founder of AlgEvolve, says the main principle behind the company's technology is to use algae to clean wastewater in the same way that it does naturally in lakes, rivers, and streams.

"Phosphorus is the reason for algae blooms in lakes and rivers, and we are bringing the algae to the plant here to grow so it uses up the nutrients in the wastewater before it goes into the river," McGraw says. "Algae have been cleaning water in nature forever. The only two byproducts of the process are pure oxygen and the algae biomass."

Those leftover algae, he says, potentially could be reused in a number of ways, such as being burned as a biofuel.

If Inland Empire Paper were to implement a full-scale wastewater treatment system using AlgEvolve's technology, Krapas says the plan likely would be to burn the leftover algae to heat the mill's steam boilers, which also would further offset the mill's use of natural gas.

In 2009, the mill installed a new pulping system that offset its use of natural gas by more than 75 percent. That also reduced its carbon emissions by about 30,000 pounds per year, he adds.

McGraw says that during the recent test pilot the treatment cycle took about an hour from start to finish, but adds that time likely would be less for a full-scale operation at the paper mill.

During the water-treatment process the algae also consume carbon dioxide, further helping to offset the mill's carbon emissions, McGraw says.

Before going into AlgEvolve's system, the water coming out of the mill's secondary treatment system is a brown, tea-like color. After it comes out of the algae-cleaning process but before the algae is filtered out, the water is green. When the algae is removed, the water changes from green to a light tan, and despite that coloration, McGraw and Krapas say the harmful nutrients, such as phosphorus, nitrogen, and the leftover organic matter, are down to levels so low that it wouldn't be detrimental to the river.

The hope is that the reclaimed water could be reused in the mill, Krapas says.

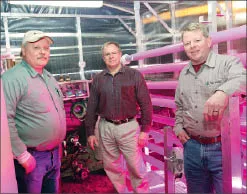

For the recently completed test pilot at Inland Empire Paper, AlgEvolve operated its system in a small, 300-square-foot greenhouse and two 100-square-foot trailers.

For a full-scale treatment system that would be able to handle the 3 million gallons of wastewater per day produced by the mill, Krapas estimates that several 100-foot-long greenhouses would be needed.

He adds that it's not clear yet as to how much of an investment a full-scale algae-based treatment system would be, but that a cost estimate likely would be determined after the next stage of testing.

McGraw says, "The benefit of the system is that it's modular and scalable, so customers don't have to invest into a full-scale operation; it can be added on to gradually and as needed."

Now that the fourth test of AlgEvolve's system has wrapped up, McGraw says the company will analyze the data it collected during its pilot to create a report for Inland Empire Paper. That report will be used to engineer the next scale of testing, which likely would be set up to process up to and 100,000 gallons of the mill's wastewater a day.

Krapas says the hope is to have that larger treatment system in operation by the end of the year.

He says then another a year of testing would need to take place to ensure that the technology still is effectively able to treat a much higher volume of wastewater.

One of the major concerns, he says, is that time is running out to have a system in place capable of removing the amount of phosphorus from the wastewater that the state Department of Ecology is calling for.

"Because of the time frame we are in, we have to make a decision very soon on which path we want to follow," he says. "We are running out of time to explore other alternatives. Seven years sounds like a long time, but when you look at where we're at after eight years of testing and exploration of other technologies and we still don't have a solution, I'm glad we started when we did."

Related Articles

_c.webp?t=1763626051)

_web.webp?t=1764835652)