Home » Kaiser Aluminum's Trentwood site cleanup moves ahead

Kaiser Aluminum's Trentwood site cleanup moves ahead

Removal of contaminants expected to cost up to $18 million

February 2, 2012

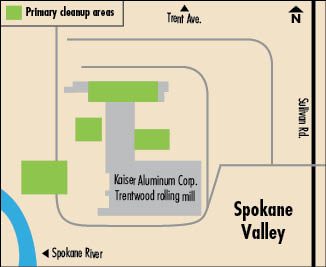

At the order of the Washington state Department of Ecology, Kaiser Aluminum Corp. recently completed a draft document outlining options to remove contaminants found in the soil and groundwater at its Trentwood aluminum rolling mill in Spokane Valley.

The removal of those contaminants, which have been identified at five different sites within the facility, could cost up to $18 million, says Bud Leber, environmental manager at Trentwood.

During the last six years, Leber says, the Foothills Ranch, Calif.-based aluminum products manufacturer has invested about $12 million into previous contaminant cleanup efforts there. Kaiser's efforts to remove such contaminants at the Trentwood site have been ongoing for decades, he says.

The aluminum mill is located at 15000 E. Euclid and just north of the Spokane River on a 512-acre site that lies over the Spokane Valley-Rathdrum Prairie Aquifer.

The recently completed cleanup plan draft is the result of a 2005 legal agreement Kaiser entered into with DOE to conduct a remedial investigation and feasibility study of the Trentwood site.

Some of the contaminants found during Kaiser's remedial investigation of the groundwater and soil at the Trentwood mill include petroleum-based fuels, polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB), diesel, heavy oil, gasoline, arsenic, chromium, lead, iron, and manganese.

Not all of those contaminants are found at each of the five sites included in the cleanup study, and the substances are present in varying levels at those sites, DOE says.

The concern is that the soil and groundwater contaminants could end up in the Spokane River through runoff, or could seep into the aquifer, says Teresita Bala, who's overseeing the cleanup effort with DOE's Spokane office, located at 4601 N. Monroe.

Leber says that Kaiser has been working since the late 1970s to clean up environmental contaminants that resulted from the 70-year-old mill's early operations. The Trentwood facility's history dates back to World War II when it was operated by the U.S. government to produce aluminum used in military aircraft, he says.

Because of the threat of enemy sabotage during the war, many of the fuel and chemical tanks and transfer lines there originally were installed underground, and leaks from those tanks contributed to the contamination there, Leber says. Kaiser removed and replaced many of those tanks in the late 1980s and early '90s, he says.

To address the petroleum that still contaminates some of the groundwater at Trentwood, Kaiser also around that time installed several recovery wells with pumps that skim the oil off the surface of the groundwater, Leber says.

There also now are more than 100 monitoring wells around the facility that measure groundwater contaminant levels, he adds.

Since 1994, Kaiser has recovered more than 4,000 gallons of petroleum through this process, Leber says.

During the next phase of remediation efforts, one of the proposed options to clean up three contaminated groundwater sites, called plumes, also involves skimming the material from the surface of the water, as well as taking advantage of natural biological degradation processes, he says.

Two of those plumes already are being contained through current measures.

Some of the groundwater at those sites is contaminated with polychlorinated biphenyl, or PCB, which is a chemical that was used in many commercial applications before being phased out in the late '70s and then banned in the U.S. in 1979.

Humans mainly are exposed to the chemical through food sources, particularly fish, and exposure can have adverse effects on the immune system, says Jani Gilbert, a DOE spokeswoman.

She says there are advisories in place at certain sites along the Spokane River where people are cautioned not to consume fish, or to only consume a minimum amount of fish during a specified time frame, because of the chance the fish could be contaminated with PCB.

In Kaiser's cleanup draft, the company is proposing to address the presence of PCB in the largest of the groundwater plumes by pumping the contaminated water from that plume into an already contained area. The hope then is that the chemical would naturally degrade along with the petroleum contaminants, Bala says.

She says the chemical structure of PCB makes it hard to clean up compared with petroleum that hasn't dissolved into the groundwater.

Bala says because there isn't much scientific data to show that PCB could naturally break down under such circumstances, Ecology would require Kaiser to perform a test pilot study to show that this method of remediation is effective in addressing the contaminant.

"We need additional information to find out if this is working or will work, and if this meets regulations, so we'll ask them to do some interim actions that will show that the degradation of PCB is occurring at the site," Bala says.

She adds that up to a year of data could be needed from a test pilot to prove that this measure would be effective before large-scale cleanup efforts could begin.

To address contamination in soil at various locations at the Trentwood site, Kaiser is proposing to remove around 33,000 cubic yards of soil contaminated with PCB, diesel, heavy oil, gasoline, metals, and carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (cPAHs).

Kaiser's remedial investigation at Trentwood shows there's a risk of human exposure to the contaminants there, but that there aren't any risks of exposure to wildlife within the site included in that study.

As with the contaminated groundwater plumes, the soil contaminants also are located at various depths and in different concentrations.

He says cleanup work in other areas could begin before the test pilot of the proposed PCB removal method is complete. It's not clear at this point how long it could take to remove all of the existing soil and groundwater contaminants at Trentwood, he says.

Bala says the recently released draft documents outlining Kaiser's proposed cleanup options are available for public review until March 6, and any comments or questions may be directed to her until that date. The technical documents resulting from Kaiser's remedial investigation and feasibility study are available for public review on the agency's website, at www.ecy.wa.gov, on its toxic cleanup page.

After the public comment period ends, she says, DOE will put together its own draft cleanup plan that will incorporate any public concerns and that also could differ from the options Kaiser is proposing.

Latest News

Related Articles