Home » Former Boeing lean manufacturing expert brings efficiencies to WorkSource Spokane

Former Boeing lean manufacturing expert brings efficiencies to WorkSource Spokane

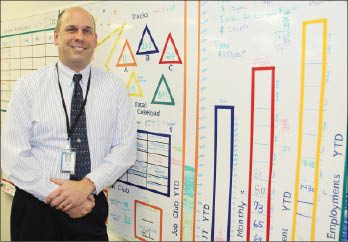

Former Boeing engineer John Dickson puts stamp on WorkSource Spokane

March 15, 2012

Impatient to help match jobless clients with employers, former Boeing Co. engineer John Dickson is applying "lean" process-improvement skills he learned in the private sector to a Washington state employment agency office here that he now heads.

Dickson is Spokane County area director for the Employment Security Department, overseeing the WorkSource Spokane one-stop job services center, which seeks to help unemployed state residents find jobs.

The center last year dealt with 28,000 job seekers, helping put about half of them back to work, and Dickson says he expects that percentage to rise this year as the economy picks up. Moreover, putting quality over quantity, he says he wants to make sure he's providing employers with the workers who have the skills or potential they need.

Since the fall of 2009 when he began working with WorkSource Spokane as a contracted lean consultant—he was named to his current post nine months ago—he has engineered a range of changes aimed at providing speedier, more tightly targeted services to job seekers. He also has taken steps to motivate staff to help identify areas for possible improvement and has set up a tracking system to measure results.

"The main message I'd like to share is that this is not your 'typical' state government agency anymore," Dickson says. "We still have a long way to go, but by implementing new products like our 'Pathway to Employment' process, we're proving that a state government agency can indeed be very lean, efficient, and customer focused."

The changes, some generated through staff initiatives, have included streamlining the agency's administrative processes—even by reducing substantially the amount of office supplies it buys and stores—and freeing up counselors to do more job coaching rather than searching cabinets for clients' files.

The transformation here come at a time of severe budget constraints in which state agencies are under pressure to operate more efficiently. Gov. Chris Gregoire issued an executive order late last year directing all agencies to adopt "lean" process-improvement principles and tools. Crafted originally by Toyota, such techniques have been shown to increase efficiency and reduce waste and have been embraced widely by businesses across the U.S.

A number of state agencies already have worked in partnership with Boeing to implement such processes, but Dickson has shown particular zeal within the Employment Security Department to develop them here, others at that agency say.

He oversees a staff of about 100 people, most of whom work at the job center at 130 S. Arthur, east of downtown Spokane. The center has an annualized budget of $6.9 million for its July 1, 2011-through-June 30, 2012 fiscal year.

The Pathway to Employment process that Dickson refers to walks job seekers through a customized four-phase approach focusing their job search, assembling their marketing materials, promoting themselves to employers, and 'acing' their interviews.

Additionally, that process enables job seekers, who he refers to repeatedly as "customers," to schedule appointments with WorkSource employment coaches, and Dickson claims it virtually has eliminated waiting time.

"Customers at times in the not-too-distant past would have to wait for over an hour to receive a service," he says. "Now, very few customers ever have to wait to be served, and if they do, it's for no more than five minutes."

A key change that he brought with him from Boeing was the creation of visibility, or "viz," boards—basically dry-erase whiteboards showing bar charts and various data that are updated continuously and that Dickson says have become essential tools for monitoring progress. Each morning, a leadership team visits every operating unit's viz board in the center, and front-line employees provide updates on process-improvement activities and performance.

While the sheer number of job seekers the agency helps find jobs certainly is important, another crucial factor is "are we helping employers" find the best applicants for the openings they have, Dickson says.

"I call it the eHarmony business. I try to match them up," he says, making an analogy to the popular Internet dating website.

The lean management philosophy that he applies to his work boils down to two fundamental principles—continuous improvement and respect for people, Dickson says.

The first principle, he says, requires "understanding our system values," as defined by customers, and eliminating non-valued-added processes, meaning those that customers wouldn't pay for voluntarily if a part of fee-based services.

The second principle involves respecting staff members by enabling those closest to the process to improve it.

"People support a world they help create," and lasting process improvements occur when employees, particularly those on "the front lines," are given the opportunity to provide input and make decisions that are incorporated into how the office operates, Dickson says.

"Anything I do is aimed at the front-line staff," he says, "You have to understand who your true 'value-adders' are."

Also crucial to the whole process, and something he's encountered while doing a lot of "myth-busting" with employees resistant to change, is the need to develop a "learner" rather than a "knower" mindset, Dickson says.

"'Knowers' inadvertently constrict the success of our organization. What I've found is that you have to become a learner, constantly learning," he says. "As I moved up the management ranks at Boeing, I tried never to forget that."

Dickson grew up in Spokane, graduating from Lewis & Clark High School in 1981, and holds a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Washington in Seattle and a master's in engineering management from Washington State University.

He worked for Boeing for 23 years after earning his bachelor's degree, and says he held leadership roles there in the Sea Launch, B-2 bomber, F-22 Raptor, 777, and 787 programs. While there, Dickson says, he was the F-22 program's lean director and helped create a lean system that won "Best in Boeing" recognition in 2003 and 2004. The system enabled F-22 wing assembly flow time to be reduced from 75 days to 35 days and a fuselage assembly from 60 days to 35 days. It also greatly reduced the amount of factory floor square footage required to do the work, tripled productivity, and earned him and his teams a number of performance awards, he says.

Of his years at Boeing, Dickson says, "I learned a lot of lessons, mostly by falling on my face," but gained valuable knowledge about how to apply lean processes effectively.

He left that company in 2006 to become area director here for Dale Carnegie leadership training programs, which has been a big passion of his, and then worked from 2007 through most of 2009 as general manager of Berg Integrated Systems, in Plummer, Idaho.

That startup company, owned jointly by the Coeur d'Alene Tribe of Indians and Spokane Valley-based Berg Cos., made huge, soft-sided military fuel bladders, and Dickson says its sales grew while he was there from $2 million to $28 million. He left that company when its sales began to decline, though, and says it folded within about a year later when government contracts for the bladders dried up, but he adds, "It was a great lesson in how to run a company."

He opened his own consulting firm, Dickson Consulting Services, and began working as a contracted lean consultant to WorkSource Spokane in October 2009.

"It was my first taste with government," he says. "People were working hard, but they weren't working smart." And if you were a customer, "we were treating you like a baton" to be passed from one person to the next, he adds.

The biggest problem, he says, was "We didn't have a standard way of doing what we do."

Working with then administrator Janet Bloom at that time, he says, "We would go into every unit and 'process map'" to develop a better sense for how to apply the continuous-improvement process there. He was at an advantage, he says, because having come from the private sector, he "had nothing to unlearn."

Also, though, he says, "I was shocked at how great this organization was, but how little it's understood across our region."

His contract ended in June 2010, but Bloom retired right about then, and Dickson—through fortuitous timing and due to the favorable impression he had made—was appointed by then-area director Frankie Arteaga to fill that vacancy.

He moved up from administrator to the higher-ranking post of area director June 1 of last year when Arteaga was promoted to a position in Olympia, although she still maintains an office at WorkSource Spokane.

Overall, Dickson says he's pleased with the improvements that have taken place at WorkSource Spokane since he came aboard, but he calls it a work in progress.

"The more disciplined an organization, the more flexible it is to change. All I do here is to try to force the action," he says. "There's a constant sense of urgency in me to keep providing high-value services.

He adds, "For me, success is when our processes are more repeatable, and literally week after week our processes are getting more stable. When you stabilize a process, you can improve it."

Of reaching the high level of performance he envisions in his mind's eye, he says, "Are we there yet? No. Are we closer? Heck, yes."

Latest News

Related Articles