Home » Guide to help employers get workers back on the job

Guide to help employers get workers back on the job

Effort aims to put people on clock within three days

November 20, 2014

A Washington State University Spokane nursing professor has published a guide to help employers and employees with job-related injuries get back to work, using a $138,000 grant from the state’s Safety & Health Investment Projects (SHIP) Grant Program.

Denise Smart, a WSU College of Nursing professor, worked with a team of medical professionals to develop the manual. Other members of the team include included Spokane occupational therapist Dr. Marilyn Wright, WSU Vancouver assistant clinical professor Dr. Melody Rasmor, and several practitioners with Spokane’s Rockwood Health System

Getting workers who have a job-related injury or illness back to work as soon as possible, preferably within three days, is the focus of the 35-page manual created for employers, as a result of the grant. A DVD, with Spanish and Russian subtitles, also was produced by the team, and is included with the manual.

The guide titled the “Early Return to Work Toolbox for Employers and Supervisors,” outlines how employers can encourage injured workers to return to work quickly, as well as modified work options for injured workers. The guide describes best practices for employers in dealing with health care and insurance providers, examples for new employee orientation, and required steps for employers managing injured workers.

Currently, workers injured on the job in Washington state stay home about eight days on average, Smart says.

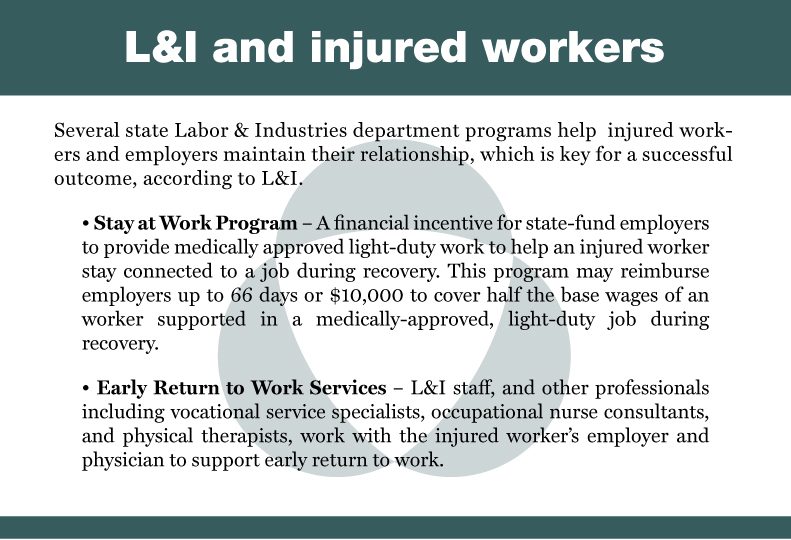

Helping injured workers return to work as soon as medically possible is a high priority of the Washington state Department of Labor & Industries, says Rena Shawver, L&I spokeswoman. L&I hosts several related programs, including the Early Return to Work Program, the Return to Work program and the Stay at Work program, Shawver says.

Returning to work speeds an injured worker’s recovery and reduces the financial impact of a workers’ compensation claim on the employer and the workers’ compensation system, she says.

“The key is to act quickly. The Early Return to Work program encourages return‑to‑work options much earlier in the claims process, to everyone’s benefit,” Sawver says.

The Early Return to Work team in Spokane helps about 16 injured workers return to their employers each month, she says.

Smart says getting back to work after an injury on the job benefits the employee as well as the employer.

“Research shows that it takes workers who stay at home longer to recover,” Smart says. She adds that workers who do return to work early usually can retain their former wage level, reduce their stress level, and maintain their self-image as a productive employee.

Smart’s team gathered information from surveys and interviews of employers, occupational health medical care providers, as well as from L&I research, which gave the team focus for the guide, she says.

Employers who allow workers to return to work early, even with restrictions on the type of work they can do, can decrease costs in time loss, medical expenses, and insurance premiums. Smart says some employers don’t realize that L&I might be able to reimburse a company for part of the salary of workers who return to work, and an injured employee can provide useful labor, even if they return to light-duty work.

“Washington Labor & Industries may pay half the worker’s salary, up to 66 days or $10,000, as an incentive for employers to take injured workers back to work in its Early Return to Work/Stay at Work programs,” she says.

Smart says she talked with many employers who were reluctant to get employees working again.

“Employers will say they don’t have light-duty work or modified-duty tasks for injured workers,” she says. “But by sitting down with employees, they can find out what additional skill sets an employee has. And within each job description there are tasks that fit what a worker can do.”

Smart says the guide encourages employers to think about the bits and pieces that make up each worker’s job, and to look for tasks an employee can do within whatever restrictions they may have. The manual offers suggestions for modified job tasks within certain job categories as well.

The guide outlines steps employers need to take working with health care providers and employees, as well as example forms and where they can be found online.

Smart advises employers to establish a “culture of early return to work” from an employee’s first day of employment as part of employee orientation.

She says employers may want to appoint an in-house specialist, possibly a supervisor or human resource employee, to manage such employees. She recommends that specialists work with injured workers to track progress with health care providers and facilitate filing forms and general case management.

“It may be the owner in a small company or workers’ compensation specialist in a medium-sized company. In some cases it may be an occupational or physical therapist,” Smart says.

Specialists can be tasked with completing paperwork and helping supervisors determine what modified tasks are appropriate given imposed work restrictions. They also may monitor work to make sure employees stay within their prescribed work restrictions, she says.

SHIP grants are available to employers through a grant program under the Division of Occupational Safety and Health within L&I. SHIP funds safety and health ideas that prevent workplace injuries, illnesses, and fatalities, and also projects for developing and implementing effective and innovative programs for injured workers.

Return-to-Work SHIP grants are still available to employers, and L&I has $650,000 to award before June 30, 2015, Shawver says.

The Journal reported earlier this year on the L&I Stay at Work Program. In that program, 1,028 injured workers in Spokane County were helped between January and October of this year, with medically approved light-duty jobs. The L&I Stay at Work Program reimbursed 271 businesses nearly $2.2 million in wage reimbursements, says Shawver.

Products, training, guidelines and other materials created under the SHIP grant program, including the aforementioned manual developed by Smart, are accessible for download free from L&I’s website.

Latest News Up Close Education & Talent Government

Related Articles

Related Products

Related Events

![Brad head shot[1] web](https://www.spokanejournal.com/ext/resources/2025/03/10/thumb/Brad-Head-Shot[1]_web.jpg?1741642753)