Senate bill would create justice centers to aid seniors

Spokane, Clark counties could host pilot program

Washington state Sens. Andy Billig, D-Spokane, and Annette Cleveland, D-Vancouver, Wash., are co-sponsoring a bill that would create two elder justice centers—one in each senator’s city—in a pilot program designed to help protect seniors from abuse and financial exploitation.

The elder justice centers, as described in the bill, would be “senior-focused centers that serve to coordinate a multidisciplinary approach to the prevention, investigation, prosecution, and treatment of abandonment, abuse, neglect, and financial exploitation of vulnerable adults.”

A vulnerable adult is defined as a person who is 60 years of age or older and is unable to care for themselves due to functional, mental, or physical disability.

Billig says the bill, SB 5788, has bipartisan support and is a response to both the increased numbers of reported abuse of seniors, as well as the expected increase in the sheer number of people over age 85 in the state over the next two decades.

The latest figures available from the 2010 U.S. Census Bureau showed 827,677 adults in Washington state who were over age 65, with 117,271 seniors in the state over age 85. The number of Washingtonians age 65 and older is projected to exceed 1.5 million by 2030, Billig says.

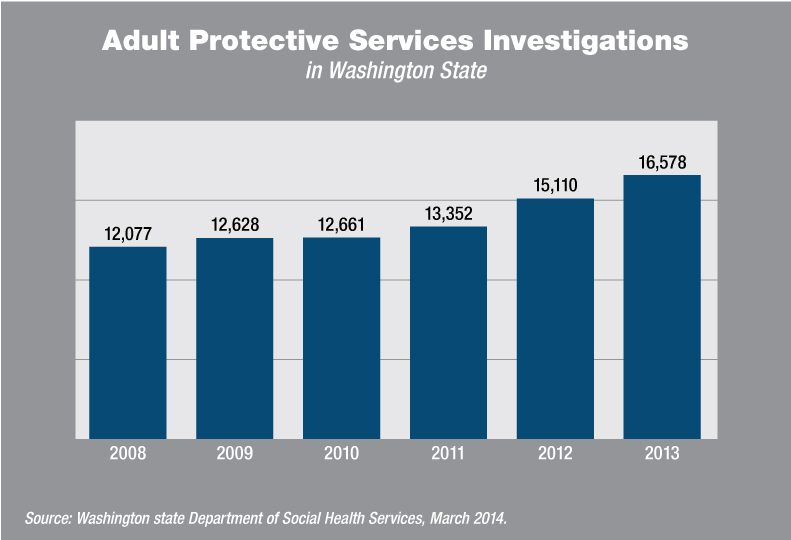

The state Department of Social & Health Services’ Adult Protective Services division reported a 37 percent increase in investigations of reported allegations of adults from 2008 through 2013, says Kathy Morgan, Olympia-based DSHS chief of field operations.

In 2013, the latest year for which information is available, Adult Protective Services conducted more than 16,578 criminal investigations of incidents targeting elder residents statewide, compared with 12,077 cases in 2008, Morgan says. Of approximately 21,700 allegations in 2013, 30 percent were categorized as financial exploitation, 17 percent concerned mental health, 17 percent were cases of neglect, 7 percent were investigations of physical abuse, and 6 percent involved general exploitation of a senior, she says. The remainder of cases included sexual abuse, abandonment, self-neglect cases and others.

Billig says Washington legislative research also shows that the majority of cases involving the elderly go unreported out of embarrassment, confusion, or fear of being cut off from family or loved ones.

“Creating this pilot program is really a response to the aging population, and it’s one of the core functions of government to protect our most vulnerable citizens,” Billig says. “We want to make sure there is a multidisciplinary collaboration between adult protective services, a prosecuting attorney, community agencies, law enforcement, a victim’s advocate, and a program coordinator—and that they’re all on the same team,” he says. Heightened collaboration and coordination will be more efficient in serving victims, he contends.

Billig says the elder justice centers would be modeled after similar children’s advocacy centers where strides have been made in child abuse awareness and protection.

“Too many elderly people are being neglected, abused or taken advantage of, often with increasingly complex and targeted crimes, and our response should include a justice system capable of providing the specialized support and protection that our elders need and deserve,” Billig says.

“Our elders raised us and in turn, they deserve our protection now,” he adds.

DSHS’ Morgan says mandatory reporters in the state, which include medical professionals, dentists, and social workers, among others, are required to report suspicions if they think a vulnerable adult is a victim of abuse, abandonment, neglect, or financial exploitation.

Owners or employees of nursing homes are considered mandatory reporters as well, she adds. If a mandatory reporter fails to report nursing home abuse or neglect, he or she may be found guilty of criminal inaction. Morgan says DSHS also receives reports of elder abuse from the public.

“We get a lot of calls from the public, but there is very little self-reporting,” she says.

Morgan says that taking advantage of a vulnerable adult runs a wide gamut of scenarios, including taking money from seniors, transferring resources of a vulnerable adult, and taking money from bank accounts.

Mental abuse, she says, can be verbal and can include verbal assault, harassment, or unreasonably confining someone, among many other things. Morgan says she’s even seen a case in which people put a victim on a leash and led the person around in public. She says keeping someone in isolation, away from family and friends, also can be defined as mental abuse.

Allegations of neglect are also investigated by DSHS, Morgan says.

“Neglect is when a dependent adult is not being provided the basic necessities of life, like shelter, clean clothing, or is not fed by a person who has a duty of care over an elderly person, to maintain physical health,” Morgan says.

Billig says the pilot program will show whether the justice centers can be effective in impacting the problems. The law itself outlines a schedule for submission of progress reports to the governor and the legislature during the next three years, Billig says.

“I think it will save money in the long term,” he says. “We all have seniors we care deeply about, and it’s up to the government to protect our most vulnerable citizens.”

By January 2018, the law would require each site to submit a final report to the Legislature detailing the effectiveness of the elder justice center models, as well as recommendations for modifying or expanding the elder justice centers and creating them in other areas across the state.

The bill, which was introduced in early February, was scheduled for a public hearing last week in the Senate Committee on Health Care. It’s expected to be sent to the Ways and Means Committee, and if passed, then sent to the floor of the Senate for a vote, Billig says.

Sen. Cleveland says while there are no funding details in the current bill, the cost for the two demonstration centers would be roughly between $1 million to $1.5 million.

“The bulk of that money would be focused on staffing,” Cleveland says. She adds that Vancouver, in Clark County, currently operates a minimal elder justice center using county funding, but there is no state statute that addresses elder abuse specifically. This bill, she says, would formalize the creation of such centers across the state.

Related Articles

Related Products