Home » Extender act, election lull lend certainty to tax filers

Extender act, election lull lend certainty to tax filers

Preparers this year don't have to wait on Congress

October 20, 2016

Permanent tax breaks enacted last December, coupled with an election-year lull in new tax laws, are enabling tax preparers and their clients here to implement strategies with more time and certainty than they’ve had in recent years, some tax planners here say.

Jason Munn, a tax partner at the Spokane office of Seattle-based accounting firm Moss Adams, says tax preparers and clients can plan in the autumn months more comfortably this year than in recent prior years, when Congress delayed decisions on popular annual tax provisions called extenders.

In recent years, clients have had to plan for multiple contingencies in regard to uncertainties over the extenders, Munn says.

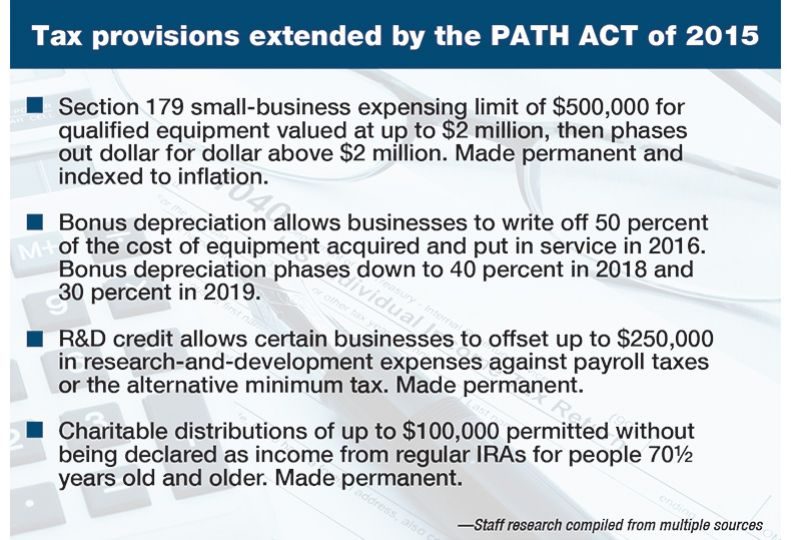

Late last year, though, Congress passed the Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes Act, which extends some provisions and makes some of them permanent, including expense allowances for certain business equipment, research-and-development credits, and allowances for certain charitable distributions.

“This year, we can go out and have normal planning discussions because things are set,” Munn says. “It gives us the freedom to do a better job of planning.”

Tina Hart, a tax adviser for Moulton Wealth Management Inc., of Spokane Valley, also says the permanent extenders aid in planning.

“We’re able to talk to clients and give them a clear heads-up into the future,” Hart says. “My phone is ringing less. There’s a little less uncertainty. That allows me to focus on certain things.”

David Green, principal at David Green CPA PLLC, of Spokane, says that in addition to the certainty the permanent extenders provide, there aren’t many other changes to the tax code for 2016.

“Major tax law changes don’t occur in major election years,” Green says. “From a big-picture perspective, nothing huge is happening other than the election itself, which will speak volumes about where we’re heading, depending on who gets elected president and who controls Congress.”

For the 2016 tax year, the bonus depreciation provision and the Section 179 provision enable business owners to plan for equipment purchases.

The section 179 provision enables businesses to deduct up to $500,000 for qualifying equipment purchases. The deduction phases out dollar for dollar once equipment purchases top $2 million.

The bonus depreciation provision enables businesses to write off up to 50 percent of the cost of qualifying new equipment and improvements purchased during the year. The bonus depreciation allowance is extended through 2017 and is scheduled to phase down to 40 percent for property placed in service in 2018 and to drop to 30 percent in 2019.

Munn says that in prior years, when the provisions were approved late in the year or even retroactively, “We sometimes had only a week or two to spread the word to clients to see if they wanted to buy equipment real quick.”

With the R&D credit now also permanent, startup businesses also will have the option to use the credit to offset up to $250,000 in payroll taxes or alternative minimum taxes.

“That’s a lot for a startup company,” Munn says of the R&D payroll-tax offset. “It’s something I’m talking more about with clients with early-stage companies.”

New R&D regulations issued by the IRS in recent weeks enable companies that develop software for internal use to claim R&D credits if certain functions or data can be accessed by third parties using the software.

“We will certainly be taking a closer look and discussing this again with our clients,” Munn says.

The alternative minimum tax is still a problem for some middle-class taxpayers, he says.

The AMT is intended to ensure high-income filers don’t escape paying taxes through otherwise allowable credits, deductions, and loopholes.

Congress indexed the AMT to inflation in 2012 to reduce the number of middle-class taxpayers in the AMT bubble.

“Many higher earners aren’t getting hit with the AMT because they are paying a higher rate anyway,” Munn says. “A lot of folks who might be in the middle class are creeping into the AMT.”

Hart says one extender provision enables taxpayers who are more than 70 ½ years old to make tax-free charitable distributions from their individual retirement accounts.

Some retirement-aged people have other income sources and don’t need income from their IRAs, she says. However, anyone with a regular IRA is required to withdraw minimum amounts from their accounts at age 70 ½.

Under the PATH Act, filers of that age can elect to distribute up to $100,000 annually to qualified charities without having to declare the distributions as income.

“They don’t have to pay taxes on it if it’s a direct transfer to charity,” Hart says.

Aside from extenders, tax rates on capital gains remain lower than regular income tax rates, at least for now, Hart says.

The base tax rate on capital gains tops out at 20 percent, roughly half of the 39.6 percent tax rate for regular income for taxpayers in the highest income-tax bracket, although an Affordable Care Act surcharge of 3.8 percent also applies to investment income for high-income earners.

Hart says another Affordable Care Act tax increase is scheduled starting next year for people over 65.

Currently, a person over 65 can deduct medical expenses that exceed 7.5 percent of income. That minimum threshold will jump in the 2017 tax year to 10 percent of income, which will be in line with the threshold for younger taxpayers.

Munn says that regardless of how people view the Affordable Care Act, which is still being phased in since Obama signed it into law in 2010, clients are talking about the burden of the rising cost of health care coverage.

“Some employers are having to reduce the percentage that they pay for employees, because it’s getting too expensive,” he says. “Some employers who used to pay 100 percent of health insurance costs now pay 70 or 80 percent.”

Green says one looming tax issue is a new set of regulations the IRS is proposing to limit the ability of families with closely held business interests to take valuation discounts.

Under current tax law, family members involved in transfers of ownership in portions of a family-owned business can claim a discount corresponding to the actual market value of the share of the business.

In a hypothetical example, Green says, that if a company owner were to transfer ownership of 10 percent of a $100 million company to a family member, the family member likely wouldn’t be able to sell that share for $10 million.

“Maybe 10 percent of the company would be worth 65 to 70 cents on the dollar as determined by a third-party appraiser,” he says.

Yet, the IRS is proposing to disallow such discounts, meaning such transfers would count against the grantors’ lifetime gift or estate tax exclusions at full value, he says.

The federal individual lifetime gift and estate tax exemption for 2016 is $5.45 million.

The IRS has published the proposed regulations and currently is accepting comment on them.

Senate Republicans have requested the IRS withdraw the proposed regulations and House Republicans have introduced two bills to nullify them, although the Obama administration has indicated it supports the proposed changes.

Green says he has some clients with family business interests who are in their 90s and who might want to take advantage of the discount while they still can.

For Washington residents, transferring business ownership before death could help avoid the state death tax.

“Washington state doesn’t tax gifts, but it does tax estates,” Green says.

The state’s estate tax exemption is $2.08 million.

Green says, however, that he might have different advice for business owners in their 50s who don’t want to give up that much control when they anticipate 30 to 40 more years of life.

Latest News Up Close Banking & Finance

Related Articles

Related Products

Related Events

![Brad head shot[1] web](https://www.spokanejournal.com/ext/resources/2025/03/10/thumb/Brad-Head-Shot[1]_web.jpg?1741642753)