Executive pay surges in the Inland Northwest

Huge gains for mining company's brass boost otherwise soft year

Total compensation for executives at Inland Northwest-headquartered publicly traded companies surged last year, but it wouldn’t have if not for a fortunate—and long-awaited—turn in Gold Reserve Inc.’s unusual odyssey.

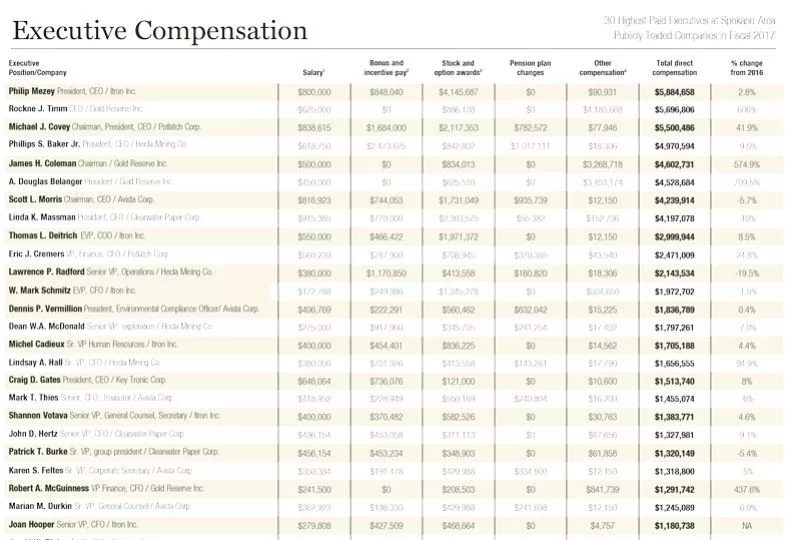

According to the annual analysis conducted by the Journal of Business, average annual total compensation for 40 executives at eight public companies based in the Spokane-Coeur d’Alene area came in at $2.01 million, up 23 percent from total compensation for the same group in 2016.

The anomalous jump compares with a 3.8 percent increase in total compensation in 2016, a rebound from a 2 percent drop the previous year that had snapped a five-year streak of compensation gains.

Results for 2017 are skewed by one-time payments each of Gold Reserve’s named executive officers received in the third quarter of last year that resulted in triple-digit pay increases, ranging from 438 percent to 710 percent.

The reason for the jump extends back to 2008, when the government of Venezuela expropriated Gold Reserve’s primary mining asset, which at the time was named the Brisas Cristinas and was expected to be the largest gold mine in South America once developed. Gold Reserve sued the Venezuelan government later that year, kicking off a well-documented, years-long legal battle that resulted in a judgment in the Spokane-headquartered company’s favor worth $1 billion-plus.

The parties modified settlement terms, and now, Gold Reserve and Venezuelan government jointly have begun developing the mine, now called Empresa Mixta Ecosocialista Siembra Minera.

Years before the settlement, however, Gold Reserve had issued to its executives what it called retention units, which were intended to attract and retain key personnel and motivate them to achieve long-range goals, according to the company’s proxy issued earlier this year. The company sold its mining data to Venezuela as part of their agreement in June 2017 and paid out those retention units, which accounted for a large portion of the pay increases, though those executives also received bonuses and other perquisites.

The company reported that it doesn’t have any additional retention units outstanding.

Due to the Gold Reserve anomaly, median, which is the midpoint in a set of data, figures tell a much different story than averages. Median annual executive compensation was $1.32 million, down 0.5 percent compared with $1.33 million the previous year for the same set of executives.

If Gold Reserve’s executives are taken out of the equation, the trend in executive compensation is down. Total annual average compensation for executives from the other seven public companies included in the analysis is $1.8 million, down 0.2 percent from the previous year.

The Journal’s analysis is conducted using information public companies disclose to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission in annual proxy statements. Total pay for named executive officers includes stock options and grants, pension plan changes, and other compensation in addition to salaries, bonuses, and incentive pay. Consequently, total compensation typically is far more than executives actually take home.

When factoring in only salary and bonuses, the analysis suggests the average executive took home less in 2017 than in the previous year. Average annual salary and bonus for the 40 executives last year was just over $830,000, down nearly 5 percent from the previous year. Median data show a steeper drop of 7 percent, to $635,000.

That’s a big difference from the trend in the Journal’s previous analysis. In 2016, most executives appeared to take home substantially more than they did a year earlier. That year, average salary and bonus increased 25 percent, to about $839,000 from $672,000.

Each analysis contains a different mix of executives, due to a variety of factors, including retirements, new hires, and other changes in the executives involved. Consequently, compensation figures from one study aren’t comparable to data from the next analysis.

While Gold Reserve’s executives skyrocketed up this year’s executive pay chart, Itron President and CEO Philip Mezey topped this year’s list with total compensation of $5.88 million in 2017, edging out Gold Reserve CEO Rockne J. Timm, who came in at $5.7 million in total compensation.

In 2017, Mezey led Itron as it completed two huge acquisitions. That June, the Liberty Lake-based maker of utility meter-reading technology completed its $100 million acquisition of Peak Holding Corp., owner of Norcross, Ga.-based energy-management company Comverge. Three months later, Itron announced plans to acquire San Jose, Calif.-based Silver Springs Networks Inc. in a transaction valued at $830 million.

Michael J. Covey, chairman, president, and CEO of Potlatch Corp., came in a close third with total compensation of $5.5 million. Like Mezey with Itron, Covey shepherded Potlatch through a major expansion when the Spokane-based wood products company merged with Deltic Timber Corp., of El Dorado, Ark. The merger, completed in February, resulted in the formation of PotlatchDeltic Corp. and kept the corporate headquarters in Spokane.

Phillips S. Baker Jr., president and CEO of Coeur d’Alene-based Hecla Mining Co., finished fourth on the list with total compensation of $4.97 million, but he had the highest salary and bonus among Inland Northwest executives, at about $3.88 million.

In all, 31 of the 40 executives had total compensation exceeding $1 million.

Just under a quarter—nine of 40—of the named executive officers at Inland Northwest public companies are women. While men still dominate the C-suite, women have a slightly stronger presence than in the previous analysis, when seven of the 41 executives were female.

Clearwater Paper Corp. President and CEO Linda K. Massman ranked highest among women—and eighth overall—with total compensation of about $4.2 million.

As alluded to earlier, compensation amounts include stock awards and accounting factors that don’t involve cash value of that stock. Amounts listed for grants of restricted stock and stock options, for example, use formulas to determine what the stock could be worth in the future. Consequently, an executive receiving that stock often doesn’t reap the rewards of that asset for years.

The Journal doesn’t include in the analysis gains that executives earn in a single year from having past restricted stock vest or for exercising past stock options. Since the mid-2000s, companies have included the current-year cost of such gains in their filings. Because of that, adding them could be duplicative.

Related Articles

Related Products

_c.webp?t=1763626051)

_web.webp?t=1764835652)