Multimillion-dollar Black Tank cleanup moves ahead

Decontamination effort will take more than a decade

A BNSF Railway Co.-owned site in the Hillyard area known to have oil contaminants deep in the soil is undergoing a multimillion-dollar cleanup operation to protect drinking water, without slowing down the North Spokane Corridor freeway project.

Courtney Wallace, Seattle-based regional director of public affairs for Fort Worth, Texas-based BNSF, says the cleanup will be overseen by the Washington state Department of Ecology.

“We’re all working together to protect the people and environment, incorporating public input so that we can do a responsible cleanup and also make sure that construction can go on unimpeded for the North Spokane freeway,” Wallace says.

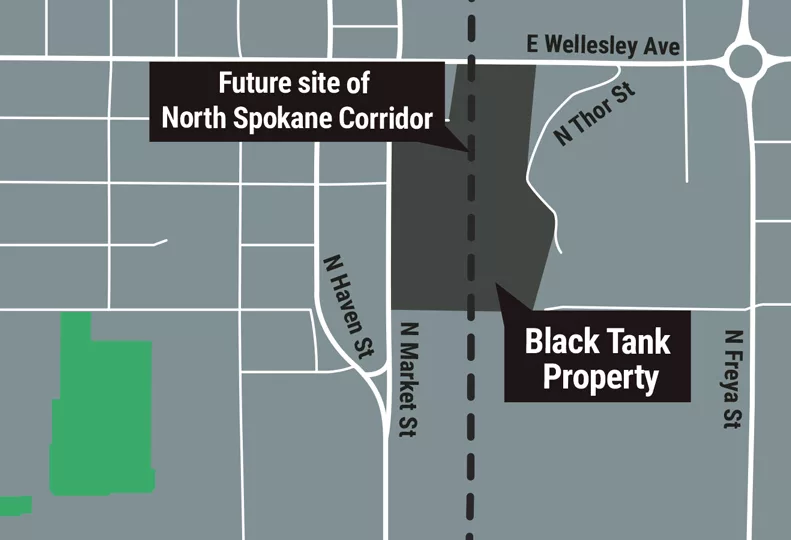

Known as the Black Tank Property, the site at 3202 E. Wellesley, in the Hillyard neighborhood, was once occupied by a massive black above-ground tank that stored petroleum products for fueling train engines.

The property is in the pathway of the planned North Spokane Corridor; the Washington State Department of Transportation earlier this year expressed concerns that the cleanup of the Black Tank site could alter the freeway’s route, requiring millions of dollars to elevate the freeway over the property. However, BNSF and Ecology say current plans will push the freeway just 15 feet west of its original planned path, allowing the Black Tank site to undergo decontamination processes during and after construction of the North Spokane Corridor.

The envisioned cleanup work includes processes called bioventing and biosparging, and could take well over a decade to complete.

Jeremy Schmidt, site manager with Ecology’s Eastern Region, says several contamination sites range in depth from 15 feet underground to the Spokane Valley-Rathdrum Prairie Aquifer some 170 feet underground, including a 9,150-square-foot column of contaminated soil.

Ecology held a public meeting at the Northeast Community Center last month to hear what the public had to say about the site.

“At the public meeting and from public comments from past public outreach efforts, we have heard that the public wants the site cleaned up in a pragmatic fashion, and that they would prefer the cleanup of the site doesn’t hinder or substantially modify the design and construction of the North Spokane Corridor freeway project,” Schmidt says.

The department’s public comment period for the cleanup plans closed June 11, and the comments are under review. Schmidt says that if the comments don’t warrant changes to the planning documents, the department will begin final soil and groundwater remediation efforts for the rest of the site.

Bioventing and biosparging will be employed at the Black Tank Property. Those methods involve forcing air underground into soil and ground water, providing oxygen to increase the activity of micro-organisms that break down petroleum in the soil and on the groundwater. Ecology estimates such cleanup will cost about $5.5 million and take 14 years to complete.

Schmidt says those methods were chosen because they will remedy the contamination faster than other methods and can be used during and after construction of the North Spokane Corridor.

“This remedy can be co-located with the North Spokane Corridor — the remediation under and around an operating freeway are compatible,” Schmidt says.

Schmidt says that if Ecology determines that bioventing and biosparging will take more than 20 years to clean the site, a remedy called steam enhanced extraction could be used. In that method, steam would be injected into the ground in order to heat the petroleum before pumping it to the surface. The Department of Ecology says a combination of bioventing, biosparging, and steam enhanced extraction would cost about $19.5 million and would take 10 years to complete.

Last year, Ecology excavated the top 15 feet of three of the five surface soil contamination areas and part of a fourth, according to the department’s fact sheet on the site. The two remaining areas were too close to existing BNSF railroad tracks to be excavated. The tracks will be relocated before those sites can be excavated.

A 7-acre plume of a heavy oil called bunker C permeates the soil that rests on groundwater, Schmidt says. The fact sheet states that the site is located above part of the Spokane Valley-Rathdrum Prairie Aquifer, which is the designated primary source of drinking water for Spokane and Kootenai counties. However, because the oil hasn’t mixed with the water, drinking water supplies are safe; it will continue to monitor the oil’s presence on top of the aquifer as cleanup efforts begin to ensure the oil remains separate from the water supply.

Ecology notified BNSF in late 2011 and Houston-based Marathon Oil Co. in early 2012 that the companies were potentially liable for contamination cleanup and costs associated with it.

A representative of Marathon Oil didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

BNSF’s Wallace says the property had served as a locomotive fueling station for decades.

“In the late 1800s, our predecessor railroad, Great Northern, constructed the yard,” Wallace says. “Around 1999, we notified the Washington state Department of Ecology of ground surface contamination and began working with Ecology on getting cleanup approval.”

In 2006, BNSF removed the 50-foot-diameter black tank for which the site is named, as well as 10,270 tons of contaminated soil.

According to Ecology’s fact sheet on the Black Tank Property, BNSF discovered petroleum contamination in a monitoring well in 2008.

Related Articles

_c.webp?t=1763626051)

_web.webp?t=1764835652)