Home » Wheat farmers cope with low market values, tariffs

Wheat farmers cope with low market values, tariffs

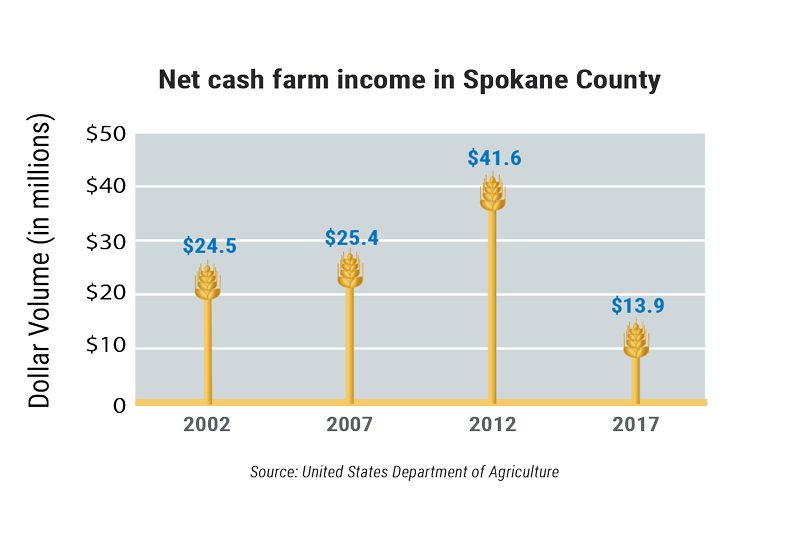

Census reveals decrease in county farm income

July 3, 2019

Over the past several years, the rip saw effect of falling wheat prices and climbing expenses has slashed income for wheat farmers, industry experts and local farmers say.

Despite the recent addition of tariff-related pressures, however, some remain optimistic that relief could be on the horizon.

According to the 2017 U.S. Census of Agriculture, which is conducted every five years by the United States Department of Agriculture, net cash farm income in Spokane County dropped by 67% from 2012 to 2017, and the total market value of products sold decreased by 22% during that period.

Chris Mertz, northwest regional director for the USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service, says part of decrease in income is due to the fact that 2012 was an especially profitable year for wheat.

“I remember when the 2012 numbers came out, I said, ‘This is going to be kind of an odd year,’” Mertz says. “That year, we had lower inventories and higher prices. Our average market year price in 2012 … for all wheat in the state of Washington, was $8.70 per bushel.”

By comparison, the 2017 average market year price was $4.85 per bushel.

The market value of all wheat grown in Spokane County in 2012 was just over $75,000; by 2017, that value dropped to about $30,000.

While wheat production increased statewide by about 4.7 million bushels, Spokane County’s wheat production dropped by about 2.7 million bushels.

Glen Squires, CEO of the Spokane-based state industry agency Washington Grain Commission, says wheat farmers also have been grappling with high operations expenses and stagnant income.

“The cost of everything – fuel, inputs, taxes – goes up, but the price per bushel isn’t much different than it was 20 years ago,” Squires says.

Marci Green, a wheat farmer and owner of Green View Farms Inc., located near Fairfield, says the farm economy in general has tightened, but wheat farmers in particular have been struggling to keep up with operations expenses.

“When the price of wheat was up, the cost of our inputs went up also,” says Green, who also is a past president of the Washington Association of Wheat Growers. “When the price comes down, the price of our inputs doesn’t usually come down, so therefore our margins get a lot tighter. The price was up a little more two or three years ago, but the input costs have also gone up significantly.”

Green View Farms’ largest expense is equipment, Green says. She says the farm has been finding ways to decrease equipment costs in order to balance out the lower market prices of wheat.

“There are some pieces of equipment we have bought jointly with neighboring farmers. We share it, so we only have to pay part of the cost,” Green says. “We’ve also looked at leasing some equipment, rather than buying.”

Green says the farm has also been investing in more high-tech solutions to reduce costs.

“We use precision agriculture. A lot of that is GPS systems, which reduce the amount of overlap that we have,” Green says. “So, if we’re spraying chemicals, we’re not spraying part of the field twice.”

Green says some farmers who have been unable to cope with rising costs and declining income have chosen to retire, while others have left the farming industry altogether.

Other farmers, Squires says, increase their acreage in an attempt to produce more wheat. Green says some of these farms increase acreage by buying the land retiring farmers sell.

Farmers have also been affected by ongoing trade disputes, Green says. As previously reported in the Journal, total wheat exports from Washington slipped by about 8% last year; Green says nearly 90% of wheat grown in Washington is destined for export.

“We were selling some wheat to China before the tariffs, and as soon as the tariffs went on, it went to zero,” Green says.

The impact of trade disputes on wheat farmers can’t be quantified, Green says.

“It’s one of those things where we don’t know where our markets would be without the uncertainty, so you can’t really put a price on it,” she says.

Green says that when tariffs are brought up in the global political conversation, customers become uncertain about the future of their trade relationship with U.S. farmers, and begin to view those farmers as unreliable sources of commodities.

“In Japan, for example, the wheat industry has spent 60 years developing a relationship with the Japanese millers and bakers,” Green says. “Now that’s in jeopardy because we’re not part of the CPTPP.”

The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership is a trade agreement between several countries, including Canada, Japan, Mexico, Australia, and Chile. It was formalized in early 2018 and went into effect Dec. 30.

Green says that she and other farmers are hopeful that a new trade agreement with Japan can be forged in the near future.

“Once you lose those markets or you lose market share, it’s very difficult to get that back,” she says.

Farmers also have been feeling the squeeze of tariffs on materials needed for production, Green says. In 2018, the U.S. implemented tariffs on steel and aluminum coming to the U.S. from all other countries, with the exceptions of Canada and Mexico.

“We kind of get it from both sides,” Green says. “It’s harder to sell our product in the global marketplace, and the cost of our inputs goes up because we’re paying the tariffs to bring things into our country.”

Green says most farming equipment is made from steel, as well as storage facilities such as grain silos.

“I know people who were planning to put up new grain storage facilities, and then the steel tariffs went on and the price went up so significantly that they postponed building their new facilities,” Green says.

While trade disputes continue, Mertz says the outlook for wheat production this year is somewhat more positive than recent years – he compares outlooks for harvest volume and market prices to the 2012 crop. Wheat crops are behind schedule in the Midwest, while parts of Australia have struggled with droughts.

“It’s a global market, so if some countries are doing poorly, sometimes we get higher prices for what we have, and vice versa. Some areas of our country are doing poorly, so some commodities in other parts of the country benefit from that,” Mertz says. “We’ve been noticing that the commodity market’s prices are going up. With inventories potentially decreasing, this year could end up being a higher market average price year.”

Green says wheat farmers throughout the state expect crops of average or above-average production.

“We are optimistic. It’s not a huge crop, but it should be at least average,” Green says. “In the southern central parts of the state, they’re actually getting close to harvesting. In our area just south of Spokane, we probably won’t be harvesting until August.”

Whether market prices rise to match production volumes, Green says most farmers will find ways to remain flexible.

“We have good years and we have bad years, and it’s been that way since the beginning of time,” Green says. “Farmers are pretty resilient. We work hard to adapt to the challenges and work toward efficiency. We’ll continue to do that, and hopefully we don’t lose too many (farms) along the way.”

Latest News Up Close Government

Related Articles

Related Products