Home » Spokane weighs impact fee adjustments by district

Spokane weighs impact fee adjustments by district

Planning board mulls adding up to $1K per trip

August 1, 2019

The city of Spokane is exploring a change to its impact fees code that has the potential to add or save thousands of dollars for developers, depending on which district they’re building in.

Several local developers and community leaders say, however, that increased fees might deter building in certain areas.

“I think it’s going to hinder (development), because not only will we have the price of construction, material, and labor, adding impact fees makes projects almost impossible to pencil in a development,” says Kevin Edwards, associate at development company Hawkins & Edwards Inc. “Anytime you add fees to a development you run the risk of developments not happening because they get too costly.”

The impact fees, which were first passed in 2011, are fees gathered from developers to mitigate road and traffic impacts associated with development.

The city first began exploring changes to the impact fees in 2017, however, the changes were put on hold in September of 2018 and were reintroduced at the Planning Commission’s July 24 workshop.

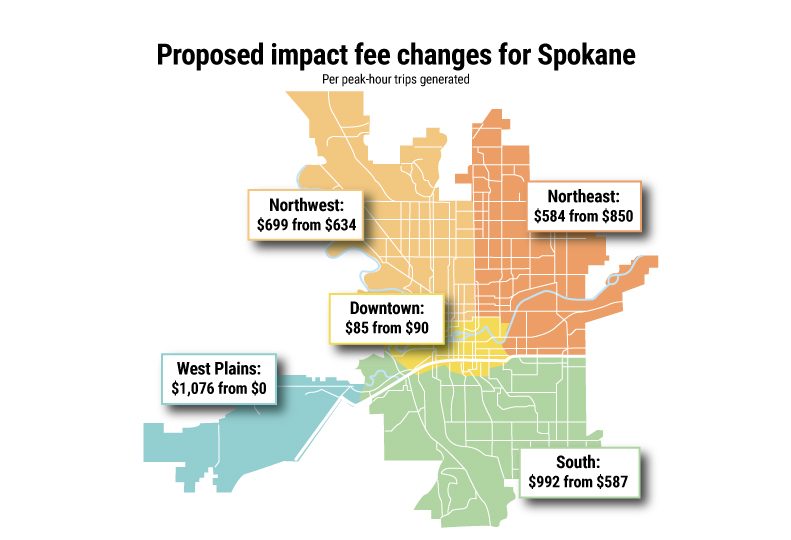

If the update is adopted, the impact fees applied to the five districts in Spokane will change. The downtown district will drop to $85 from $90 per peak-hour trips generated. The northwest district will increase to $699 from $634 per peak-hour trip generated.

The south district will spike to $992 from $587 per peak-hour trip generated, while the northeast district will decline to $584 from $850. Developers on the West Plains will incur the highest fees, with the city proposing $1,076 per peak-hour trip generated.

Joel White, executive officer of the Spokane Home Builders Association, says he’s concerned about Spokane implementing more fees at a time when the city is experiencing a housing crisis.

White contends that the fees may force developers to go elsewhere or further drive up home prices - which already have increased 10.9% through the first six months of the year, compared to the year-earlier period, June, according to the Spokane Association of Realtors’ median-price data.

“Prices go up when you see new impact fees,” he says. “We’re trying to figure out why now, what’s the purpose?”

Edwards says he believes the fees are necessary, noting that if a developer adds traffic to an at-capacity roadway, it makes sense that the company should be proportionally responsible for mitigating the increase in traffic.

He adds, however, that the fees on the West Plains seem high, and questions the justification behind a larger impact fee for the West Plains when compared with fees in other parts of the city.

White notes that with the level of ongoing development on the West Plains, a high fee makes sense to support infrastructure needs.

The fees only apply to land within Spokane city limits.

The West Plains wasn’t included in the original impact fee code, because it wasn’t included in the city when the fees were established. A portion of the West Plains was annexed into the city of Spokane in mid-2011.

The affected area would follow U.S. 2 just past Hayford for the West Plains, along with a few parcels to the south and southwest of the airport, says Inga Note, the senior traffic planning engineer with the city of Spokane who presented the proposed changes to the Planning Commission.

Land owned by the Spokane International Airport is exempt from these fees, says Note. The reasoning is that the airport is an independently governed organization that has its own capital set aside for infrastructure improvements, she says. Because of this, the city appointed impact fees advisory committee determined it wasn’t appropriate to include the airport in the fee update, she says.

Impact fees are determined by the amount of capital the city projects it will need for infrastructure improvements, Note explains, so districts that require more infrastructure projects saw the biggest jumps in fees.

For example, fees in the Northeast district dropped because of the completion of the Havana Street project and because less funding is needed for remaining infrastructure projects, she says.

The city determines the cost of needed projects within the separate districts and consults a travel demand model, then determines the rate per trip needed to pay for the projects, she says.

The assumption is that developers will pay for 50% of the total infrastructure project cost, Note says, while the city pays for the other 50%.

For example, fees gathered from developments in the south district would be used for intersection improvements at 29th and Regal and the widening of the northbound approach on 44th and Regal to two lanes, while fees gathered from developments downtown would be used for a new traffic signal at Fifth Avenue and Sherman Street and a signal lane on Washington Street and North River Drive.

The city already has set aside $1 million for qualified projects within either the Northeast Public Development Authority or the West Plains-Airport Area Public Development Authority as an incentive for developers to build in those areas, she says.

The funds are meant to reduce or eliminate impact fees for qualifying projects, Note says, with the idea that the city would cover the costs using the set aside funds.

The money would be used on a first-come basis, and isn’t currently written into the code, so as soon as the funds are gone, that's it, Note says, unless action is taken by the city council.

For example, based on the proposed fee per peak-hour trip generated, a pharmaceutical manufacturing company developing a 63,000-square-foot facility in the West Plains PDA would save an estimated $74,300 in impact fees, she says, while an industrial park of 500,000 square feet in the Northeast PDA would save roughly $370,000 in impact fees.

A 120-unit apartment complex in the West Plains PDA likely would save nearly $69,900, she says.

Project types that would qualify are manufacturing and production facilities, industrial, warehouse and freight, hotels, offices, and residential buildings, though the commission debated the merits of including hotels, offices, and residential buildings at the July meeting.

The commission opted to defer the decision until the hearing this month.

The advisory board also recommended revising the deductions a developer can receive off their total impact fee for building bicycle and other alternative transit improvements. For example, a developer could receive 10% off the total impact fee for building or improving a transit stop, or 20% off for building a bike and pedestrian path or road connection.

The maximum deductions would be raised to 30% off the total impact fee from 20% if the update is approved.

White says SHBA will be following the proposal closely as it proceeds through the Planning Commission. He says there are still a lot of questions about the reasoning behind the fee changes and what kind of impact it will have on developers and adds that he doesn't understand why the city is looking at changing the fees and what the ultimate goal is.

Note says a Planning Commission hearing is scheduled for Aug. 14, during which the parameters of the changes will be determined.

Latest News Real Estate & Construction Government

Related Articles

Related Products