Home » Kindergarten readiness worsens in Spokane area

Kindergarten readiness worsens in Spokane area

United Way, others look to lower cost barriers to early learning programs

November 21, 2019

Both locally and statewide, the majority of kids aren’t entering public schools “kindergarten ready,” state data show, and the problem appears to be getting worse.

This has led some nonprofits to explore how to provide more access to early learning.

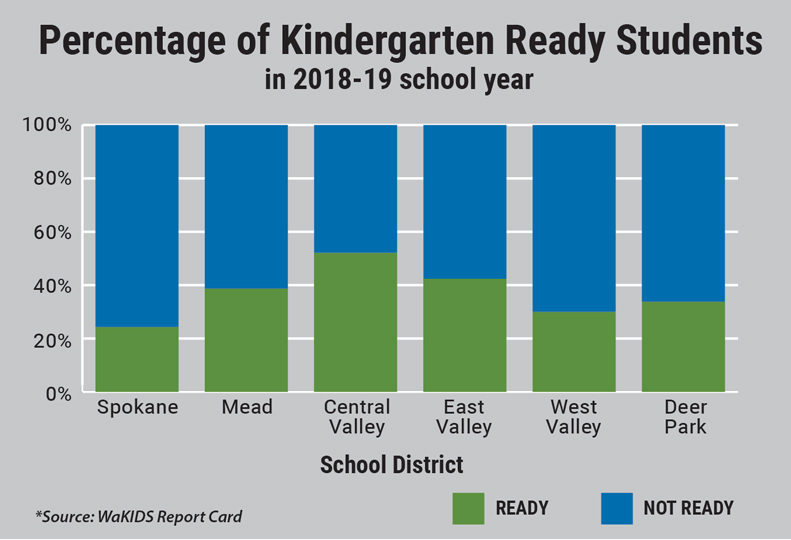

The 2018-2019 Spokane School District report card paints an especially grim picture, with only 24.3% of children entering kindergarten performing at the appropriate age levels in all six metrics -- a 0.6% dip compared with the year earlier and a 5.7% fall compared with the 2016-2017 school year.

Statewide, 45.7% of children entering kindergarten were assessed as kindergarten ready, a 1% drop compared with the year earlier, according to the WaKIDS report card.

Studies have shown that students who start behind often struggle to catch up to their peers, says Sandra Szambelan, director of the Center for Early Childhood Services for the NorthEast Washington Educational Service District 101.

“That’s really the state’s impetus of looking at children as they enter school, because we know that research shows us that kids who start behind, stay behind … it’s really important that we look at the whole system and the whole ecosystem around that child.”

Other school districts within Spokane County received higher readiness rates than those of Spokane Public Schools. In Mead School District, 38.7% of children entering kindergarten were observed as meeting age-appropriate levels in all six metrics. In Central Valley School District, 52.1% were kindergarten ready, while in East Valley School District, 42.4% were observed as kindergarten ready.

In the West Valley School District, 30% of kids entering kindergarten hit all six metrics; Deer Park School District saw 33.8% of students meeting the appropriate metrics.

All districts, except Central Valley School District, saw declines year-over-year in the percent of children assessed as kindergarten ready.

In response to the issue, nonprofit Spokane County United Way has placed more emphasis on funding programs dedicated to providing early learning services to low-income and at-risk children and working with families, says Sally Pritchard, vice president of community impact for the nonprofit.

“It’s a priority for us, and one of the things we are looking at is where else should we be investing the dollars that are entrusted to us,” she says.

Ten years ago, Washington state legislators launched the Washington Kindergarten Inventory of Developing Skills to assess incoming kindergarteners on whether they meet the age-appropriate metrics, with an eye on better situating students to excel as they progress through school.

When entering kindergarten, kids are assessed on six metrics: cognitive, language, literacy, math, physical, and social-emotional. Those assessments are performed by the students’ teachers, who are trained to observe the students and determine if the children are performing at the appropriate levels, Szambelan says.

The assessments are subjective and involve three stages: an initial meeting with the child and their parents to gain insights on the family dynamic, a six-week observation and assessment period when the child enters kindergarten, followed by teacher meetings with early learning providers in the community to compare metrics.

Szambelan says the goal of the assessment is to start a dialogue between the teachers, families, and early learning providers to increase continuity and better align the pre-K and kindergarten programs.

Pritchard contends Spokane’s numbers reflect a lack of access to early learning programs.

“If you look at access to preschool, we have a smaller percent of kids, 3- and 4-year olds, who are attending preschool than the state average,” Pritchard says.

The cost of early learning or preschool programs for children through the age of 5 is comparable to college tuition, and the younger the child, the more expensive the program, says Szambelan.

There must be at least one employee for every four infants. For older children, the employee-kid ratio is around 1-10. This leads to higher costs for those providing programs for younger children.

Child Care Aware of Washington, a nonprofit, statewide child care resource and referral program, reports the median month price of care for infants in child care centers in Spokane County is $969, while the median monthly cost for toddlers is $815. The median monthly cost for preschools in Spokane County is $748, while the median cost for school age children is $477 a month.

Pritchard adds that families usually spend as much or more on child care as they do on housing.

According to health district studies, she says, “Less than 50% of families in Spokane County use formal child care when their kids are young.”

The state provides child care subsidies, she says, but contends that the subsidy rates don’t cover the full cost.

A subsidized rate is the amount the state pays to a provider to care for a child who qualifies for a subsidy, typically a low-income family.

According to the 2018 Child Care Data Report compiled by Child Care Aware of Washington, the subsidy rate for Spokane County is $754 for an infant. Meantime, the 75th percentile -- the rate at which 75% of providers charge less and 25% charge more -- for an infant is $1,083, well above the subsidy rate.

Andrey Muzychenko, director of community investments at United Way, says the public policy goal is to have the subsidy rates equal the 75th percentile rate for a county, “so low-income children have access to 75% of the total licensed child care slots available.”

For preschool children, the subsidy rate in Spokane County is $600, while the 75th percentile cost for such child care is $839, a $239 difference.

United Way of Spokane County partners with five area nonprofits, says Muzychenko.

For the 2020 fiscal year, which started July 1, United Way has a budget of $187,500 it’s investing in its partners’ early learning programs.

Its partners are Joya Child & Family Development, Children’s Home Society of Washington, Community-Minded Enterprises, Transitions, and the YMCA of the Inland Northwest. The nonprofit also works with The Salvation Army Spokane Sally’s House emergency foster care receiving center, he adds.

For the first time, the nonprofit invited the five partners this year to share their performance metrics with one another to compare what is common between them and where programs can improve, he says.

Pritchard says the funding United Way provides is meant to fill the gap between the subsidy and provider rates.

“What we try to do is pay attention to issues and who are the right community partners standing in the middle of it trying to address needs,” she says.

She adds, “(We recognize) that what United Way can put into it is a drop in the bucket,” compared with state and private investments.

“It’s a major community issue and it needs to be addressed at multiple levels. The state can’t do it alone,” contends Pritchard.

Latest News Up Close Education & Talent Government

Related Articles

Related Products