Preterm birth rates haven't declined in decades

Wide variety of risk factors said to be contributing to persistently steady rates

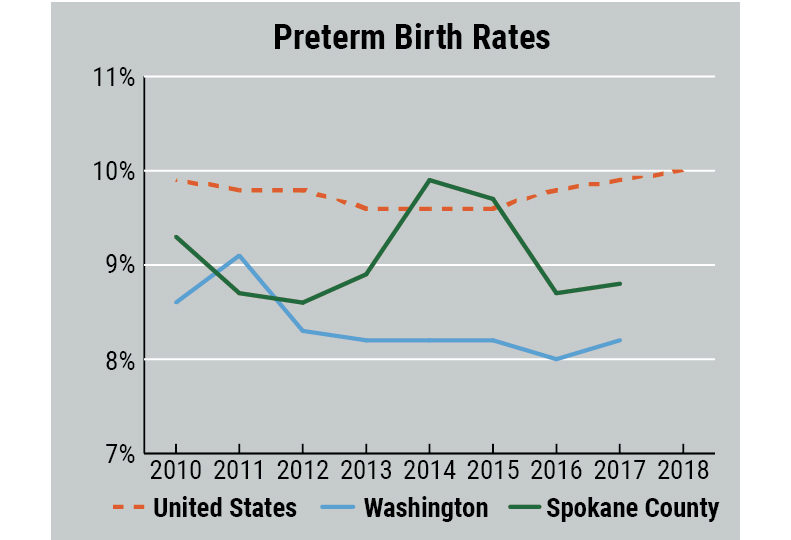

Preterm birth rates from the local to the national level have remained fairly stable for the past few decades, but some in the obstetrical care community say the fact rates haven’t declined is frustrating.

In November, national nonprofit March of Dimes released its preterm birth rate report card for cities and states throughout the country.

Washington state earned a B-minus with a preterm birth rate of 8.3%; Spokane’s rate is slightly higher at 9.2%, also earning a B-minus grade from March of Dimes. Those rates haven’t changed much in the last 20 years: in 2000, the state preterm birth rate was 8.5%, and Spokane County’s rate was 9.8%.

Dr. Jason Reuter, obstetrician and gynecologist with Spokane Obstetrics and Gynecology PS, located within the Providence Sacred Heart Doctor’s Building at 105 W. 8th, says it’s encouraging that preterm birth rates aren’t rising. However, he finds it frustrating that rates aren’t declining, and nobody can figure out why.

“Despite all of our medical technologies, despite all of our interventions, we haven’t made a dent in the rate. We’ve eliminated a lot of risk factors for cancers, but how do we tell patients not to have preterm birth?” Reuter says. “We’re just sort of witnesses to this process, and that can be very humbling in that we don’t have a lot of answers.”

Preterm birth is defined as a live birth before 37 completed weeks of gestation. A full gestation period is 38 to 40 weeks. A baby born prematurely can face a variety of health problems, including developmental delays, neurological issues, and hearing loss.

March of Dimes estimates the average cost of a preterm birth at $64,000, compared with a routine birth cost of about $10,000.

“Unfortunately, it costs all of us, because some of the people who are at risk are a little on the fringe of society; they may not have health care; they may not seek out that type of care urgently and immediately,” Reuter says.

Many risk factors can lead to preterm birth, including smoking, maternal age, diabetes, high blood pressure, previous preterm births, and drug use — a 2014-2015 bump in preterm birth rates in Spokane County could be attributed to the opioid crisis, Reuter says.

Race is also a risk factor; March of Dimes found that in Washington, the preterm birth rate among Native American populations is 12.4%, while black populations have a preterm birth rate of 10.2%. Reuter says those populations often show a correlation between socioeconomic status, lack of prenatal care, and higher preterm birth rates.

Because the exact order and combination of processes that start labor aren’t well understood, it’s nearly impossible to stop preterm labor. However, some medical interventions can mitigate the effects of preterm birth when a mother is in labor.

“One of those intervention points is to give steroids to mature the baby’s lungs,” Reuter says. “There’s also another medicine called magnesium sulfate, which can help prevent neurological injury during the time of birth and stabilize some of the potential neurological complications that can occur.”

Women who have had a previous preterm birth can be prescribed progesterone to help prevent another preterm birth.

Reuter says pregnant women have high levels of progesterone throughout pregnancy until shortly before she gives birth, so boosting progesterone in expectant mothers who have previously had a preterm labor can help to delay birth until the baby is carried full term.

He adds, “It’ll be interesting to see even in the next five years whether or not having (progesterone) intervention might reduce our rate even by a couple of percentage points, which could be statistically very significant.”

Reuter notes that the evidence doesn’t show that additional progesterone prevents preterm labor in women who haven’t previously given birth preterm.

Until the mechanisms and processes that initiate labor are better understood, Reuter says proper health care is one of the best ways to avoid a preterm birth.

“What women can do is have routine prenatal care and have a good relationship with their provider, because if they do, they’re much more likely to at least have an intervention,” he says.

Education could also be an effective method of decreasing preterm birth rates, Reuter says.

“I think educating women about knowing what (labor) symptoms to look for is probably our best strategy at this point, especially women for whom it’s their first pregnancy or who have never had a preterm birth,” Reuter says.

Reuter says some women who experience preterm labor are either uneducated about the symptoms of preterm labor or afraid to seek care and will avoid going to a hospital until they’re too far along in the labor for providers to intervene.

Clearing up misconceptions about what can and can’t prevent preterm births could also help, Reuter says.

“There’s no evidence out there that bed rest does anything,” Reuter says, noting one common misconception.

Related Articles

Related Products