Reimagining of Division Street begins

North Spokane Corridor may reduce traffic along longtime thoroughfare

Spokane-area transportation professionals are collaborating to re-envision what Division Street could be once the North Spokane Corridor opens.

It’s a vision that includes bicycles that were once banned from areas of the street safely zipping down greenways. Roads that were densely packed with harried motorists trying to get north of Spokane are now populated by locals out for a bit of shopping or commuting to work. Buses arrive every 7 1/2 minutes to collect passengers running their daily errands and deposits them back home to the high-density residential buildings that have taken over once dilapidated properties along the corridor.

DivisionConnects is a collaborative effort that’s helmed by the Spokane Regional Transportation Council in partnership with the Spokane Transit Authority, the city of Spokane, Spokane County, and Washington state Department of Transportation.

The project is intended to examine alternative modes of transportation along Division to determine where improvements can be made to enhance bus, pedestrian, and bike travel, says Jason Lien, project manager at Spokane Regional Transportation Council.

The project also will explore future land uses along the corridor, says Lien.

“We had started discussions with the STA and our other partners to think about the Division Street Corridor, not only to focus on transit improvements, but to think about it more holistically in terms of all modes of transportation,” says Lien.

In 2016, voters approved funding for the Spokane Transit Authority’s Moving Forward plan to improve transit in the region, including along the Division corridor, says Brandon Rapez-Betty, communications and customer service director for STA. Moving Forward is a 10-year improvement plan meant to connect workers to jobs and people to services, as well as help the region’s economic development, he says.

According to Lien, that project was the launching point for the larger DivisionConnects project.

Route 25, which starts at the STA Plaza in downtown Spokane, then north on Division to the Hastings Park & Ride, carried about 930,000 passengers in 2019. It’s the transit system’s second most-used line and is planned to be a high-performance transit line that will provide frequent, reliable, all-day service with buses arriving every 15 minutes for at least 12 hours per day on weekdays and at least every 30 minutes during evenings, weekends, and holidays.

The approximately $1 million DivisionConnects study is being funded by three agencies. SRTC allotted about $400,000 from federal funds, STA contributed $500,000 — 20% of which were local funds and the rest federal funds — and WSDOT contributed $100,000 from state funds, Rapez-Betty says.

The collaborative team is working with consultants Parametrix, which has an office in Spokane.

Planners hope to have a list of recommended improvement projects by the end of next year or early 2022, says Lien.

Those improvements could look like signed bike routes or greenways on neighboring streets to allow for more north-south access for bike riders. Such improvements could be along Division itself, or a combination of the two, he says.

Organizers are currently soliciting public input for insights into how people use the corridor and what areas they use most.

As of Sept. 29, residents had marked 67 areas as highly frequented or important locations along the corridor, which range from restaurants and retail shops, to transit areas, fire stations, and the Department of Motor Vehicles office.

One anonymous commenter noted, “To make bus-rapid transit successful, we need more residents living along Division. The parking lot of the NorthPointe Plaza is a great development site for mixed-use, mid-rise, residential buildings and would go a long way to reducing the suburban feel of Newport Hwy.”

A State of the Corridor report published in April provides some insights into where some land-use change could occur based on current zoning codes and future land-use designations determined by the city and county.

For example, some areas in downtown Spokane have been designated in the city’s comprehensive plan as primed from future high-density residential areas. The University District has been designated as institutional. In the county, land near the Hastings Park & Ride has been designated as an urban activity center, a change from mixed-use, regional commercial, and low-density residential.

“We’ll work toward identifying some of those opportunity areas and seeing where, longer term, there could be some transformation that could help benefit the bus system and accommodate economic development,” says Lien.

Lien says project organizers are working to establish focus groups comprised of people who have a stake in Division, such as business owners or those who manage space along the corridor.

“Once we have those set, we hope to have a representative cross section of people along the corridor to try to get a cross section of opinions,” he says.

Division is one of the most used streets in the city, with more than 50,000 cars traveling on it daily.

Originally called Victoria Street, the 11-mile road was renamed to Division Street in October 1891 by the Spokane City Council. It started as a four-lane road, two lanes in each direction, and was largely unpaved north of the river until the late 1920s and early 30s.

Division was widened to six lanes, three in each direction, through North Spokane in the mid-90s. It has remained largely unchanged since, though the expected completion of the North Spokane Corridor is expected to shift much of the north-south traffic from the historic highway to the new freeway by the end of the decade.

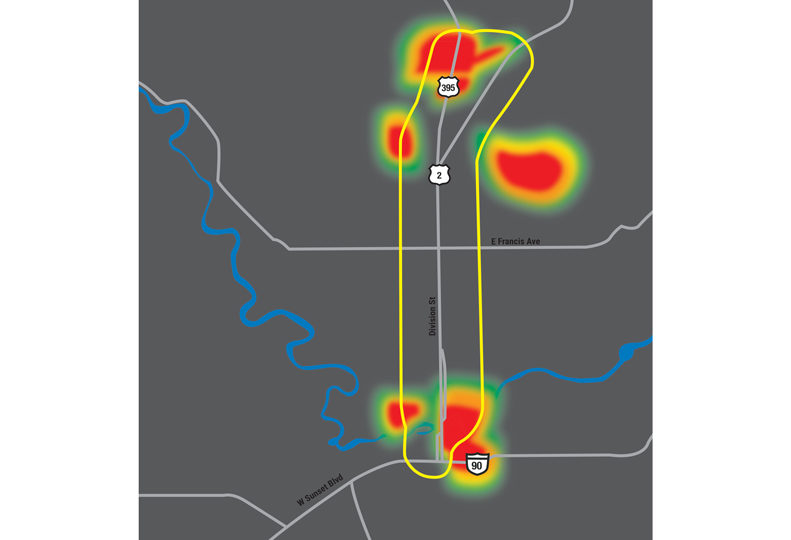

One of the aspects of the study is to model what traffic density along Division will look like once the North Spokane Corridor is complete, Lien adds.

The North Spokane Corridor is a $1.5 billion project first envisioned in the mid-1940s that will ultimately create a freeway linking Interstate 90 in east Spokane to U.S. 395 north of Spokane.

“With the NSC, you can expect some of those trips on Division will move to the NSC to move through town,” Lien estimates, however he notes that study is ongoing, and no data is available yet to add credence to the widely-held expectation.

The NSC has been underway for 19 years, and the project hasn’t been without its hiccups.

Most recently, the project hit a delay early this year with the passage of the voter-approved Initiative 976, a measure to cut car-tab taxes that jeopardized the state’s transportation budget, though a new transportation budget signed by Gov. Jay Inslee lifted the temporary pause on the NSC, as well as some other WSDOT projects around the state.

The project was then further delayed by the governor’s “Stay Home, Stay Healthy” mandate meant to curb the spread of the coronavirus. The order shutdown nonessential businesses, which at the time included construction.

The corridor’s completion is slated for 2029. As of Sept. 29, the statehad completed the Columbia Avenue to Freya Street stretch.

Related Articles

Related Products