Home » Teletherapy's popularity declines in era of isolation

Teletherapy's popularity declines in era of isolation

Providers brace for rise in demand for services

October 22, 2020

While telemedicine services treating the body are increasing in popularity, isolation and the desire for human connection are driving those seeking mental health care services back into physical offices.

Spokane area practitioners who offer teletherapy say while teletherapy use spiked during the early months of the pandemic, demand for the service has significantly tapered among those requiring more intensive care.

Jennifer Crane Pyle, community education manager of Spokane Valley-based Psychiatric Solutions LLC, says the clinic saw 60% of patients using teletherapy options during March and April, but the usage has trickled down and currently sits at about 25% of patients.

“That has been patient driven,” she says, adding “psychiatry is obviously a really personal field, and I think people like to have a more personal connection with their provider.”

However, Crane Pyle says she expects teletherapy to remain highly used post-pandemic.

The clinic not only serves Spokane proper, but several rural surrounding communities that may find teletherapy options more efficient than traveling into the city for appointments, she explains.

A number of the clinic’s patients are working professionals, Crane Pyle adds.

“What we see is that there really is a stigma about who needs (mental health care) and who receives it,” she says, adding that a common stereotype is that mental health issues lead to degradation in life, when in reality, she says, a person can be high functioning and have high mental health needs.

The clinic is in the process of surveying patients to determine satisfaction levels with teletherapy options, Crane Pyle adds, though she says she expects that “it’s a pretty mixed bag” as the service removed barriers for some, but created hurdles for others.

Dan Barth, lead for the Spokane County behavioral health task force, says the socioeconomic disparity in access to telemedicine is becoming increasingly apparent.

“Access to telemedicine needs to be at the forefront of every local legislator’s mind,” he asserts.

Barth, who is also the communications director of Inland Northwest Behavioral Health, estimates roughly 28% of patients discharged from the hospital don’t have a smartphone or access to the technology needed to use telemedicine services.

INBH is a standalone psychiatric hospital that provides specialized treatment for mental health disorders.

Barth says he’s communicated with representatives at Verizon and county commissioners about using Coronavirus, Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act funding to secure phones, wireless hotspots, and computers to provide such access to individuals who don’t currently have it.

“If we want to see people who are flourishing and doing well and not needing access to their hospital … if they have access to telemedicine, then we’re going to be a lot better off through this pandemic,” he contends.

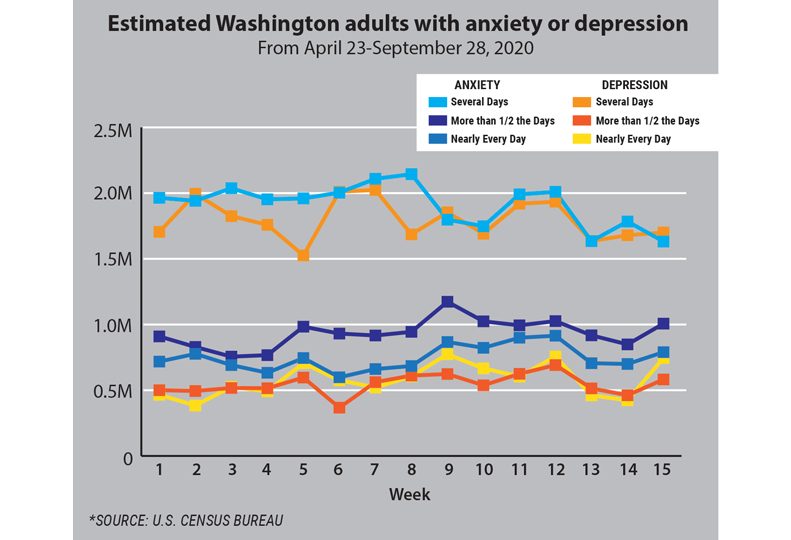

Data from the Washington state Department of Health shows nearly one in four, or 24%, of those aged 18 to 29 reported feeling down, depressed, or hopeless in late September, compared with less than one in seven, or 13%, of adults over the age of 50.

Dr. Katrina Bryant, director of outpatient services at INBH, says the hospital has been offering telehealth since the end of March, when the stay-home mandate was enacted. The hospital has been using a hybrid model since the end of May, which offers a mix of in-person and digital meetings.

“We had a couple months where (teletherapy) was pretty well favored,” she says. “They were enjoying the fact that they could sit at home. They didn’t have to worry about transportation. Then we saw a real swing around May with patients desiring to go back to in-person (sessions).”

However, Bryant notes, when the pandemic hit, roughly a third of the organization’s patients moved to one-on-one sessions with providers outside the hospital versus participating in the digital group therapy sessions because they either didn’t have the technology to use the telehealth system, or because they simply wished to not participate, Bryant says.

About 90% of patients shifted back to some form of in-person meetings in May, she adds.

Most patients who currently are using teletherapy services have lower acute mental health issues, she adds, whereas those with more acute mental health issues have trended toward needing the in-person services.

“We’re in this disillusionment, hopelessness phase of (the disaster stress cycle),” says Barth. “Statistically people are craving actual interaction with people, not digital interaction.”

INBH has seen a 365% increase in patients with schizophrenia; a 140% increase in patients with major depressive disorders with psychotic features, meaning higher instances of suicide risk; and a 60% increase in depression since the spread of the pandemic, says Barth.

Both INBH and Psychiatric Solutions report seeing increases in new patients requesting services, though both say it has been a gradual increase.

Bryant says the hospital has had increases in patients with anxiety, and that the pandemic is exacerbating the anxiety of patients who were being treated at the facility prior to the pandemic.

Across the Inland Northwest and beyond, there’s a significant demand for intensive behavioral health care with inpatient volume increasing at hospitals in the MultiCare Health System family as well as at Providence Health & Services, Barth says.

Moving into fall and winter, the state Department of Health’s Summary Forecast on COVID-19 and Behavioral Health Impacts predicts the trend of increased cases of behavioral health service needs will continue.

“Data following disasters and critical events indicate that just one month after an initial event (such as an outbreak), 10% to 33% of individuals experience symptoms of acute stress and 4% to 5% develop symptoms of PTSD, which could be roughly 380,000 Washingtonians.”

Seasonal affective disorder also is more common in the colder months when there’s less sunlight.

Further, the report notes that between 2 million and 3 million people in Washington will experience behavioral health symptoms over the next three to six months.

According to the COVID-19 Behavioral Health Group Impact Reference Guide released by the Department of Health, between six months and nine months post-outbreak is when individuals likely will shift emotionally from sadness, grief, and increased symptoms into depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

During that time period, behavioral health care providers are also expected to see a surge in patients with increased substance use, interpersonal violence, isolation, and relationship issues.

“We’re moving into the window of suicides,” says Barth, referencing the nine-month, post-outbreak mark in the report, which predicts an increase in suicide risk.

Barth says he has been working with the Spokane Regional Health District on community messaging to combat that increased risk and to help educate the community.

While the exact message hasn’t been determined, Barth says it boils down to showing people that it’s okay to not be okay and to remove the stigma around mental health.

He adds that he’s working with high-traffic companies, specifically local coffee stands, to post the information.

Further, Barth says he’s working with the doctors with Spokane Public Schools to provide resources and communication for parents, as adolescents are shown to be struggling more during this time. That includes allowing parents to elect to receive updates on their children and be sent resource options for help.

Latest News Special Report Health Care

Related Articles

Related Products