Home » Long-anticipated recession now expected by year-end

Long-anticipated recession now expected by year-end

So far, resilient economy has provided reprieve from economic downturn; rate hikes may change that

June 22, 2023

Inland Northwest economists are predicting a recession will set in toward the end of this year—later than had been previously anticipated—yet there isn’t consensus regarding projections for the length or depth of a long-anticipated economic downturn.

Grant Forsyth, chief economist for Spokane-based Avista Corp., is forecasting a historically mild recession that will begin toward the end of this year and last under six months.

“I don’t think it would be a severe one, I think it would be very short, very shallow, and it would largely be induced because of the interest rate increases,” he says.

Vange Ocasio Hochheimer, Whitworth University associate professor of economy, concurs.

“In essence, we could even look at it as a temporary slowdown of the economy,” she says.

Steve Scranton, chief investment officer and economist for Spokane-based Washington Trust Bank, also sees a recession setting in later this year, but he predicts the U.S. will enter a longer recession driven by consumers coming under financial stress.

“It will be a traditional recession—not a crisis recession like the financial crisis in 2008 or the pandemic in 2020—with an average length of 11 months,” he says. “The consumer is the key.”

Scranton says that historically, like the pandemic and the 2008 financial crisis, the Federal Reserve has responded to these crises by slashing interest rates— known as the Effective Federal Funds Rate—extremely low to stimulate economic growth. At the height of the pandemic, the near-zero federal funds rate resulted in typical mortgage rates of around 3%.

“I don’t think the Federal Reserve will intervene and suppress interest rates unless there is a problem we don’t know about,” he says.

John Mitchell, owner of Coeur d’Alene-based M&H Economic Consultants and former chief economist for U.S. Bank, says a case can be made for either scenario.

“I think the jury is still out as to whether there’s going to be a recession, or not,” Mitchell says, adding that a strong labor market has delayed the onset of the anticipated economic downturn.

Forsyth says a strong economy has made predicting the onset of a recession difficult. Last year, he had expected a recession to start in the first half of this year.

“The economy has just demonstrated it’s surprisingly resilient and resistant,” he says.

Ocasio Hochheimer explains that the U.S. has been experiencing a strong labor market resulting in part from companies reopening post-pandemic, supply chains being restored, and an overall pent-up demand for goods and services. As a result, there was a need for more workers, and the rehiring of employees that had been laid off, she says.

The natural rate of unemployment is about 5%, says Ocasio Hochheimer, and right now the U.S. is below that. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the nationwide rate of unemployment as of May is 3.7%.

The reopening of the economy, however, has caused inflation to increase substantially and prompted the Federal Reserve to increase interest rates in order to return inflation to its 2% objective, she says.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. inflation hit 9.1% a year ago, and currently stands at 4%.

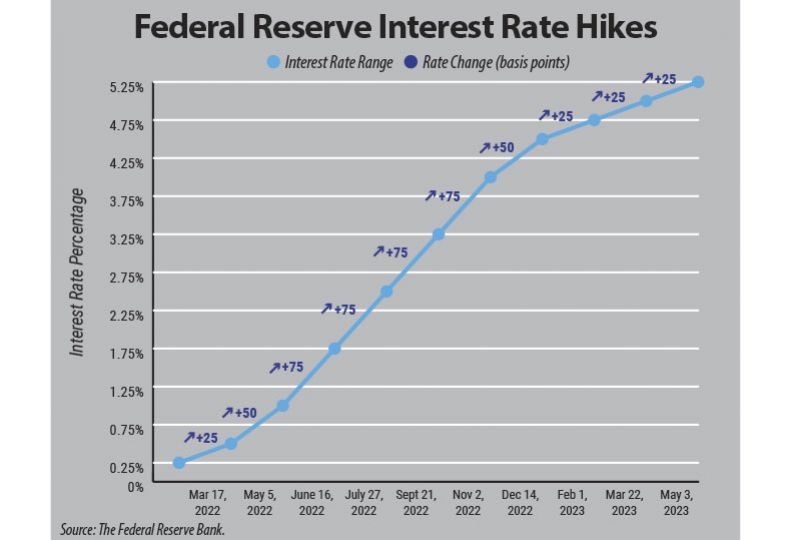

Since March 2022, the Federal Reserve has increased the federal funds rate 10 times and is at 5% to 5.25% as of May 3. On June 14, it placed a pause on its interest rate increase campaign for the first time in over a year.

Typical conventional mortgage rates currently range from just under 6% to over 7%, according to personal finance website Bankrate.com.

Scranton says the Federal Reserve likely will increase interest rates at least two more times this year by a total of half of a percentage point.

“They’re not done,” he says. “It’s a pause or a skip to assess economic data.”

The economists say they’re monitoring several factors that have impacts on the trajectory of the economy, including household debts, commercial loan activity, and the November elections.

The federal funds rate has a ripple effect on households’ debts, such as credit card payments, student loans, and mortgages, as well as commercial loans and items that tend to have a variable interest rate, says Ocasio Hochheimer.

“One thing to remember about this monetary policy is that it comes with a lag, we haven’t seen the full impact of interest rate increases,” she says.

Patrick Jones, executive director of the Institute for Public Policy and Economic Analysis at Eastern Washington University, says that the Spokane economy is heavily tilted toward service industries, which he doesn’t see as exposed to stubbornly high interest rates, with the exception of motor vehicles. Private construction projects likely will be impacted more than publicly funded projects, he says.

Forsyth says there has already been a pullback on inventory investment, which is usually a sign that businesses are preparing for weaker growth in the future.

“Sooner or later, with these higher rates and ongoing inflation issues, it’s going to move from the business side of the economy toward the consumer side,” he says.

Commercial real estate debt is one significant factor that economists here say they and their peers are monitoring.

“We still have a problem in a lot of urban areas where you have a high rate of vacancy in commercial properties, and on a lot of these properties, you’re going to have debt coming due,” Forsyth says. “The question is, how is that dealt with?”

While commercial loans are a concern, Scranton says he doesn’t think it will unravel a systemic problem, but rather will be a case-by-case issue.

“The segments under stress are retail and office commercial loans,” he says. “There will be bank and credit unions heavily exposed.”

Ocasio Hochheimer says data is beginning to show an increase in commercial real estate loan defaults.

“It’s nothing serious at the moment, but something that can turn into macroeconomic instability,” she says.

As previously reported by the Journal, office vacancies in Spokane’s central business district stood at 18.8% last fall, compared with 17.4% in the fall of 2021 and 15% in the fall of 2020. Countywide, the office vacancy rate was 12%.

According to New York City-based data software company Trepp Inc., nearly $1.5 trillion in commercial mortgages will come due over the next three years.

Mitchell explains that the lending landscape has changed since before the pandemic.

“(Loans) were made on the expectations of high occupancy rates and continued vitality downtown,” he says, speaking of city centers throughout the U.S. “In many cases, that doesn’t work anymore.”

He notes that lower occupancy rates are similarly impacting hotels in some markets. For example, San Francisco-based Hilton Union Square was forfeited to the lender by its owner in early June.

Latest News Up Close Banking & Finance

Related Articles

Related Products