Home » Pandemic increases reproductive-care barriers

Pandemic increases reproductive-care barriers

Local health agencies work to ensure access

January 14, 2021

Contraception access has decreased during the pandemic, with nearly a third of women canceling or delaying doctors’ visits, according to a recent study, which has led state and local medical professionals to find new ways to ensure access, say industry observers.

Prior studies also have shown that women are at a higher risk for unintended pregnancy during times of crisis, says Adrianne Moore, deputy director of quality improvement in Washington for Upstream, a nationwide nonprofit that partners with states to provide equitable access to reproductive health and contraception services.

“Reproductive health care … is an essential form of health care, and there should be no barrier to health care in the middle of a pandemic,” Moore adds.

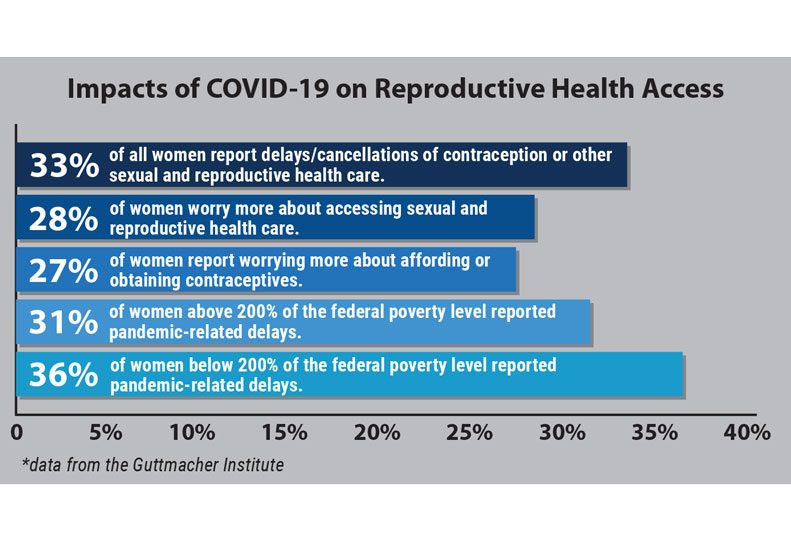

Before the pandemic, nearly half of all pregnancies were unplanned. Since the pandemic began, over one-third of women have had to delay or cancel reproductive health care, including visits for contraception, according to data from the New York-based sexual and reproductive rights research organization Guttmacher Institute.

Siobhan Shand, chief program officer with Upstream, says “Our goal right now is to really work with our health center partners to help them keep the contraceptive care lights on,” as the pandemic has exacerbated existing barriers to reproductive and sexual health care.

Partners in Eastern Washington include the Community Health Association of Spokane, Planned Parenthood of Greater Washington and North Idaho, and Family Health Centers. Upstream also has partnered with the Washington state Health Care Authority.

Upstream currently is working with 16 health care associations in Washington state, with at least 13 more expected to come online this year. It has trained over 500 frontline staff and 172 clinicians in 53 health centers, says Shand. Between those centers, Upstream has reached over 250,000 patients.

“There are obvious risks within this pandemic to contraceptive care. But I also think that we have, as a state and as a nation, really prioritized people and access to health care in new ways,” says Shand.

Health care providers have taken measures to ensure patient access, including telehealth visits that emphasize contraception education, relaxing prescription refill guidelines, and increasing mail-order prescription options, says Moore. Some providers have even hand delivered medication to a patient’s doorstep.

“Having a method that requires more of an in-person visit like an IUD or an implant is going to be more challenging to access during the pandemic,” says Moore. “Where we focus is making sure that no matter what the patient wants, that the health center knows how to get them that service or refer them somewhere.”

For example, Planned Parenthood has installed condom and morning-after pill vending machines at some of its locations as back-up access to contraception.

Other providers have worked with patients on bridge methods, or supplying a different, more accessible form of contraception when the patient’s usual method is unavailable.

A Guttmacher Institute study notes that barriers were more common among Black women (38%) and Hispanic women (45%) than among white women (29%).

Additionally, 28% of women reported increased concern about being able to access necessary sexual reproductive health care because of the pandemic, while 27% reported increased concerns about being able to afford or obtain a contraceptive method.

In the early days of the pandemic, access to contraception and reproductive health services was labeled as essential by Washington state Gov. Jay Inslee’s administration.

The Guttmacher study, which surveyed over 2,000 women nationwide early this year, found more than 40% of women changed their plans about when, or how many, children to have as a result of the pandemic.

Further, 34% of women said they wanted to get pregnant later or wanted fewer children.

Beth Tinker, clinical nurse adviser with the Washington state Health Care Authority, says measures to mitigate barriers to access also have been taken at the state level.

Overall, there has been a decrease in use of health care services across the state, primarily driven by concerns of catching the virus or infecting family members, says Tinker.

Between April 1 and Sept. 30, new enrollees in the HCA’s state funded Family Planning Only programs decreased 25% compared with the year-earlier period. Participation in the programs decreased more than 40%, she says.

The Family Planning Only services assist uninsured women and men capable of producing children with income at or below 260% of the federal poverty level, says Tinker. The programs cover every Federal Drug Administration-approved birth-control method and some family planning services to aid in avoiding unintended pregnancies.

Tinker adds, however, that several health care facilities have seen reductions in staff, either because of staff exposure to COVID-19, or staff staying home to care for high-risk family members.

At the federal level, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has allowed clients on Medicaid to continue with current coverage and eligibility, rather than having to reapply every 90 days.

Another policy change was to expand telehealth services.

While both groups admit telehealth doesn’t solve all barriers to access, both contend it has bolstered services and created new access to patients who otherwise might not have had the levels of access currently available.

The HCA expedited Zoom telehealth licenses and expanded what services can be reimbursed, says Tinker. To increase avenues of access, it certified platforms such as Facebook messenger, Skype, and Google that are otherwise noncompliant with federal medical privacy laws.

Washington state had been working on ensuring equitable access to reproductive health care since before the pandemic, having implemented a policy in 2014 allowing up to 12 months of contraception to be dispensed at once, which Tinker contends is especially helpful during this time.

Tinker says it remains to be seen whether unintended pregnancy rates will rise following the pandemic.

“I don’t think it’s unreasonable to worry a little that perhaps there will be a rise in unintended pregnancy,” she says. “The data is still emerging.”

According to Guttmacher Institute surveys, the COVID-19 pandemic had similar proportions of women shifting their fertility preferences to prefer delaying having children or having fewer children as seen during the 2008 recession.

In response to the 2008 recession, 29% of women reported being more careful about contraception use, whereas 39% of women reported these preferences as a response to the pandemic.

A quarter of women reported increased worry about affording birth control as a result of the pandemic, versus 23% following the 2008 recession.

The surveys show 39% of women reported delays in access or an inability to get contraception or other sexual reproductive health care during the pandemic, versus 24% during the recession.

Latest News Up Close Health Care

Related Articles

Related Products