Hospital-insurer fight stirs anxiety

Providence, Premera spat could have big impacts here

Employee-benefit advisers here say they're anxious to see regional insurer Premera Blue Cross and the Providence Health & Services system, which includes two of the Spokane area's largest hospitals, resolve a high-stakes reimbursement dispute.

The failure thus far by the parties to reach agreement on a new three-year contract, with the current agreement due to expire Jan. 31, could force insurance brokers and the employers they work with to scramble to adjust their health-plan offerings for next year.

"From our perspective, we think it's critically important that the two parties work out their differences and reach agreement fairly soon. We think it's critical to the community," says Mark Newbold, an employee-benefits adviser with Moloney+O'Neill Benefits. "So far, I haven't had any of our clients say they don't want to renew with Premera, but they want us to keep them apprised of developments."

Drew MacAfee, managing principal for the Spokane office of Mercer Health & Benefits, says, "I would think crunch time would come if at the end of November there wasn't significant progress made, and it would raise the level of anxiety." For now, though, he says Mercer's clients hope and expect that the impasse will be overcome before then.

Premera wants to reduce the annual rate of increase it's paying Providence to bring that percentage in line with the average of what it's paying other Washington hospitals. It contends that Providence now has a healthy operating margin, after a difficult financial stretch some years ago, and therefore should be willing to reduce the rate of increase it's seeking, in the interests of helping to contain the rising health-care financial burden on employers and patients.

Providence counters that it simply wants Premera to pay it the same for services as it gets from other insurers. Premera previously was reimbursing it at a below-cost level that was far less than what other insurers were paying, essentially forcing patients with other health insurance coverage to subsidize patients covered by Premera, it asserts. The higher-than-state-average increases it has been receiving from Premera in recent years are intended to close that gap, but have done so only partly, it claims.

Providence officials said early this month that Premera's intransigence had left them pessimistic about the possibility of reaching an agreement on a new contract before the current one expires.

"We're in fundamental disagreement on our principles. I don't see a resolution in sight," Providence CEO John Fletcher told the Journal at that time. Since then, however, the two sides have traded proposals, still without reaching an accord.

The high-stakes standoff could have broad implications for both entities, if not resolved, because of their co-dependent relationship. Providence says Premera is its largest commercial health-insurance payer, accounting for about half of its commercial revenues in the Spokane area. Premera, meanwhile, acknowledges that losing the sizable Providence hospital system from its provider network would have "significant consequences."

Providence hospitals presumably could see a substantial decline in patient numbers since Premera-insured patients receiving care at those facilities could be charged directly for the difference between Providence's charges and what Premera pays out-of-network providers, which might cause many to seek hospital care elsewhere. Conversely, Premera potentially could see its membership rolls shrink as some employers shift their business to health insurers that contract with Providence facilities.

What's not clear is which of the two is, or perceives itself to be, in the stronger negotiating position as the contract deadline approaches.

Providence Health & Services, based in Seattle, is among the largest Catholic health-care systems in the U.S., with total assets of about $7.8 billion and 2007 revenue of $6.3 billion. The system includes 26 hospitals, more than 35 non-acute facilities, physician clinics, a health plan and numerous other entities. It employs about 45,000 people in five states.

Providence Health Care, based in Spokane, is part of that system and includes the largest hospital in the network—Sacred Heart Medical Center & Children's Hospital—plus Holy Family Hospital on the city's North Side, and hospitals in Chewelah and Colville. It also includes a number of other facilities that provide assisted-living, extended-care, home health care, adult day health, and laboratory services.

Premera, meanwhile, is the Spokane area's largest health insurer by a wide margin and one of the largest in the Northwest, with 1.3 million members in Washington, and another 400,000 in Oregon, Alaska, and California. It had total revenue last year of $3.3 billion.

Providence acknowledges that its operating margin—a nonprofit's equivalent of profit—has been healthy by state regulatory standards, running at 5 percent last year, 4.9 percent so far this year, and targeted at 4.6 percent for 2009. That has been due, though, not to a high fee structure or rich reimbursement level, but rather to its focus on operating as efficiently as possible, it says.

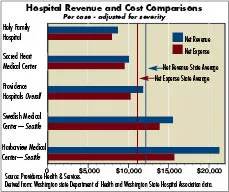

It claims that its per-case net revenue overall is 2.3 percent below the state average and its costs are 7 percent below average. That disparity is most pronounced at its Eastern Washington hospitals, it says. Sacred Heart's net revenue and net expense per case are 17 percent and 14 percent below the state average, respectively, it says, while Holy Family's net revenue and net expense per case both are 28 percent below the state average. (See chart page A1.)

Translating the publicly reported state data in another way, it asserts that 73 percent of the hospitals in the state are reimbursed at a higher rate than Sacred Heart and 92 percent have higher reimbursement than Holy Family.

For its part, Premera has said it simply is striving to combat an unsustainable, but continuing run-up in the cost of medical care. Its data show overall medical costs rising about 13 percent this year, and hospital—or facility—charges being the single biggest driver of that inflation, up nearly16 percent this year, it says.

The biggest contributor to that soaring cost, it says, and the main focus of its negotiations with most health-care providers, is what's called unit price, which is the price it pays for a particular type of service or patient. Those prices go up as the cost of running a hospital go up and also factor in growing losses on Medicare, Medicaid, and uninsured patients.

For the last five years, Premera says, it has been paying Providence an average unit price increase of 10.3 percent a year, compared with 6.7 percent for all Washington hospitals. "This variance occurred when Providence's financial picture was such that it needed help to keep its operations functioning," but that no longer is the case, it says in a position paper it has disseminated to explain its side of the negotiations with Providence.

Contrary to Providence's stance, Premera asserts that Providence's operating margin actually is several percentage points higher than the state average—after covering the cost of subsidizing its Medicare, Medicaid, and uninsured patients—and above what typically is considered necessary for long-term financial viability. Providence, in its own position paper, challenges Premera's conclusion, saying Premera used "a single data point for one year, and they chose to only talk about one segment of our organization. The reality is that we run as a health system in Washington, and that means we operate and finance all of our ministries as a network."

Countering Providence's claim that its hospitals are reimbursed at a rate lower than the state average, Premera says it actually pays them 3 percent more on average than other hospitals state wide. On the unit-price issue, it warns that every percentage point above the upper 6 percent offer it has made Providence will increase the price tag for its customers by $12 million over three years.

Providence has been unwilling to say what it considers an acceptable annual percentage increase over the next three years, citing a confidentiality agreement, but does say that it's a single-digit number. Fletcher says, though, that fast-rising health-care costs "are not going to change fundamentally'' until another cost driver, utilization, is addressed more seriously. One of the biggest things driving unit price upward, he says, is that Medicare patients are over-utilizing hospital emergency departments.

The spat between Providence and Premera has pushed negotiations that normally occur strictly behind closed doors out into public view, which both parties clearly have found uncomfortable. Negotiations got under way in January, but broke down, and the impasse became public about two months ago when Premera notified insurance brokers of the possibility that Providence might not be in its mix of covered health-care providers next year. Premera then held "town hall" meetings in six cities around the state, including Spokane, to explain the situation, present options, and ask for feedback.

Providence opted not to mount a similar public-relations campaign of that scale, complaining in its position paper that Premera was "intentionally trying to draw this out in an effort to further their own cause. This is a very disruptive tactic which we completely disagree with."

It said, nevertheless, that it wants to reach an agreement with Premera as soon as possible "to reduce the anxiety and disruption currently being caused for our patients, physicians, and staff."

Related Articles

_c.webp?t=1763626051)