Home » Preventing that second STROKE

Preventing that second STROKE

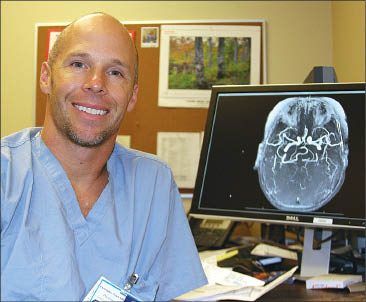

Sacred Heart is one site of national study testing use of intracranial stent with drugs

December 4, 2008

Sacred Heart Medical Center has been selected as one of about 50 sites for a National Institutes of Health study to determine if aggressive treatment of stroke victims for high blood pressure and cholesterol—along with placing a stent to widen a narrowed artery in a patient's brain—can reduce their risk of being stricken by another stroke.

The study is called the Stenting versus Aggressive Medical Management for Preventing Recurrent Stroke in Intracranial Stenosis (SAMMPRIS) trial. In it, researchers will compare the results of aggressive medical treatment for the causes of strokes with and without the stenting procedure for preventing the recurrence of strokes caused by blood clots—called ischemic strokes—in patients who have atherosclerosis, a condition that involves narrowing of the arteries.

People who suffer an ischemic stroke, the most common kind of stroke, have a 30 percent to 50 percent chance of having another stroke, says Dr. Chris Zylak, a neurointerventional radiologist and the lead researcher for the study here.

Many patients who have ischemic strokes also have atherosclerosis, says Ruthie Franks, a certified clinical research coordinator at Providence Medical Research Center here, which is coordinating the study. Another less common type of stroke not included in the study, called hemorrhagic stroke, is caused by a ruptured blood vessel in the brain, she says.

The five-year study is needed to document outcomes of the treatment regimes for stroke victims, Zylak says. There hasn't been a landmark study to determine just how effective that treating underlying conditions such as high cholesterol and high blood pressure is at reducing the risk of additional strokes, or to document the potential benefit of adding a stent to reduce the risk further, he says.

Zylak, a partner with Inland Imaging PS, of Spokane, has been placing the intracranial stent that will be used in the study in patients here for about a year.

The device, a Boston Scientific product called the Wingspan, is the only stent approved by the FDA for use in the brain.

To place the stent, the patient is put under general anesthesia. In a radiology procedure room, Zylak inserts a catheter through an artery in the patient's groin. Using real-time X-rays, called fluoroscopy, for visual guidance, the radiologist threads a wire through the artery to the narrowed portion, called a stenosis, in the brain.

First, he uses a small balloon to stretch out the blood vessel in a procedure called an angioplasty. The stent, which is loaded in a tube and ranges from 2.5 millimeters to 4 millimeters in diameter, then is guided along the wire and unsheathed in the area of the blockage. When unsheathed, the stent expands automatically, holding the artery open.

The procedure is much the same as placing a stent in one of the arteries of the heart.

"I know I can do it safely. I can tell them I can do the procedure," Zylak says. What he doesn't know, and what he hopes to help determine, is how effective stenting is in preventing strokes, he says.

In order for the intracranial stent to be considered successful and to become a mainstream treatment, it will have to be shown to reduce the risk of recurrent strokes by at least 35 percent over the course of the study, Zylak says.

"It needs to have a clear benefit," he says.

That's because there is a 10 percent chance that a patient's artery can be ruptured, causing an intracranial hemorrhage, while the stent is being placed or that the artery will become plugged again within six months, Zylak says. It's not clear yet whether a patient's stroke risk returns if the artery becomes narrowed again after the procedure, he says.

Who the study can help

Stroke patients who have atherosclerosis often are treated for underlying causes, such as high blood pressure and high cholesterol, but the treatments haven't been studied in combination with the stenting procedure, Zylak says. The SAMMPRIS study will compare both treatment methods, while gathering data on each, he says.

In addition to standard treatment with blood thinners to prevent blood clots, all of the patients will receive treatment to control their cholesterol levels and blood pressure.

About half of the patients, selected randomly, also will have a stent placed.

Zylak says he hopes to enroll about seven patients a year for the study here. Zylak and Dr. Madeleine Geraghty, a stroke neurologist at Rockwood Clinic PS, of Spokane, and director of Sacred Heart's Primary Stroke Center, will treat study patients. Altogether, the trial is expected to include more than 750 patients nationwide, each of whom will participate in the study for between one and three years. To qualify, a patient must have atherosclerosis, must have had an ischemic stroke within the previous 30 days, and must be between the ages of 30 and 80.

Once a patient is determined to be eligible, he or she will be selected randomly to receive medical management only or medical management in combination with stenting.

Making the procedure accessible

Zylak says that in addition to producing important long-term data, having a study site here will provide access to the stenting procedure for patients who might otherwise not be able to afford to have it done.

Currently, most insurance plans don't cover the procedure because it's only been FDA approved for about a year and because long-term data about it is lacking, Zylak says.

The costs of such a procedure are high, since patients must undergo general anesthesia and stay in an intensive care unit in the hospital for a time following the procedure, Zylak says.

He says he hasn't seen a recurrent stroke in any of his stent patients yet, and hopes that the treatment will prove to be beneficial.

Even if the intracranial stent doesn't become a mainstream treatment, it still could be used for patients who don't respond to other treatments, Zylak says.

Latest News

Related Articles