Home » Pacific Steel & Recycling waits out lagging markets

Pacific Steel & Recycling waits out lagging markets

Though prices are down, company says value of metal is enduring

December 4, 2008

Pacific Steel & Recycling, a venture formed here more than 100 years ago as a one-man fur-trading depot, has become a conglomeration of recycling enterprises, selling a variety of cast-off goods and commodity by-products to businesses that turn them into new products.

A supply-and-demand business, recycling has taken a hit lately as the effects of the troubled economy reverberate, but Pacific Steel's management is confident it will turn around.

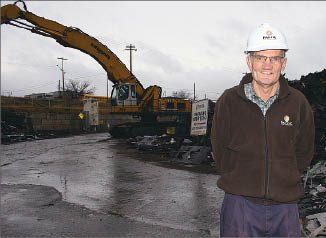

Prices for all types of recyclable materials have dropped by as much as 70 percent in recent months, causing heaps of scrap metal to build in Pacific Steel's yard here as it waits for demand to rebound. Scrap iron prices, for example, fell from $250 a ton in September to $50 a ton now, says Doug Stewart, the Spokane-based vice president of what has become a Great Falls, Mont.-based employee-owned company.

The Spokane facility employs 44 of the company's 650 employees, collecting, sorting, and baling recyclable material ranging from paper products and animal hides to scrap metal, old cars, and appliances on 14 acres the company owns here at 1114 N. Ralph, near Trent Avenue and Freya Street.

"For everything we deal in, the prices have gone down. We are price sensitive, so our volumes are down," Stewart says.

He says that when prices for the items the company handles fall, people sit on their recyclables, figuring the money they can get for them isn't worth the time it takes to haul them to the recycler. For Pacific Steel, which normally handles more than 6 million tons of metal a year, little is coming in right now, and almost nothing is going out because production has dropped at companies that buy the scrap metals Pacific Steel collects, Stewart says.

"Steel industry demand has dropped dramatically," he says.

Before the scrap metal market weakened, it had been booming for the past three years. Stewart says he thinks the market has bottomed out and will begin to recover next spring in an industry that he says has seen moderate, but steady growth here for products that its customers sell abroad. Recycling is cyclical in nature, with lines of people waiting to drop off recyclables stretching across the company's yard when demand is up, Stewart says.

Stewart says Pacific Steel will hold its own until the market turns around, which he says is bound to happen.

"The emerging countries—China, India, Indonesia—all will need steel," Stewart says. "We do business locally, but we trade internationally."

He says the conservative company can hold onto materials while the market is down, and he doesn't foresee any layoffs at the Spokane operation, at least for now.

Trading in items that have an intrinsic value will help Pacific Steel weather the current economic downturn in a business whose value is becoming more widely recognized, Stewart says.

"We used to be called junk men. Now we're 'green,'" he says, adding that more than 70 percent of steel products are recycled today, and steel has been recycled for more than 150 years.

"We bring it in, we grade it, sort it, package it, and ship it to the actual recycler that reduces it and makes something out of it," Stewart says. Pacific Steel's customers melt scrap metal down to make ingots or other products, he says. "They use what we sell them as raw material."

Though it now does business as Pacific Steel & Recycling, the company has retained some of its fur-trading history.

The company was founded in Spokane in 1896 by German immigrant Joseph Thiebes, but was incorporated in the 1920s as Pacific Hide & Fur Depot, in Great Falls, by the founder's son, Joseph Thiebes Jr. Its Spokane location is one of the largest of its 38 branch operations in Washington, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, and South Dakota. The company has been 100 percent employee-owned since the 1990s, a few years after the original owner's grandson, also named Joseph Thiebes, died, Stewart says.

Pacific Steel still buys hides and furs, mostly from slaughterhouses and hunters, which it sells to tanners who make leather goods from them. Years ago, the Spokane operation handled up to 600 hides a day, but now brings in several hundred a week, Stewart says. In homage to the company's history, Pacific Steel also operates a small retail hide and fur shop on the upper floor of its Spokane facility, where it sells leather goods and processed furs to crafters and artists.

The company also sells new and recycled steel products and remnants, which it bends, breaks, and punches holes in for its customers. Stewart says the company got into the metal procurement business during World War II, collecting scrap ferrous and nonferrous metals as the U.S. geared up to build armaments.

The biggest part of Pacific Steel's business here, however, is recycling, Stewart says. It provides container pickup service for commercial and industrial customers here with a fleet of eight trucks, and has a joint contract, along with Spokane Recycling Products Inc., of Spokane, to buy the curbside recyclables collected by the city of Spokane. Spokane Recycling also is Pacific Steel's biggest competitor here, especially in paper and plastic recycling, Stewart says. There are a small number of other scrap iron dealers here, too, he says.

A recent addition to Pacific Steel's recycling repertoire is an automobile shredder that it built last year about 20 miles east of Boise, Idaho. Stewart declines to disclose the exact cost of the facility, but says it was multimillion-dollar project.

He says the shredder has enhanced Pacific Steel's business in Spokane. Now, Pacific Steel can buy scrap cars from individuals and so-called "hulk haulers." Pacific Steel removes the fluids, mercury switches, batteries, and radiators from the cars, then compacts the shells into bales of steel and ships them by train to the Boise facility, where they are shredded into a high-grade, homogenous steel stock that steel mills melt down and reuse. The company also uses the shredder to shred large appliances, such as refrigerators, stoves, and dishwashers.

Stewart says there are some auto shredders west of the Cascades, but claims that Pacific Steel's is the only one in the Eastern Washington-Idaho area.

Latest News

Related Articles