Joint venture looks to wind

Irish, Clarkston concerns join forces to develop projects around region

A joint venture formed by a Clarkston, Wash., company and an Irish renewable-energy concern is working on several efforts to generate green power, including a proposed 200-megawatt wind-turbine farm and a 10-megawatt wind-powered project it would build with a rancher.

In October, the Clarkston company, AirDynamics LLC, which was founded by John Laney and his wife, Joani, and another couple, joined forces with Gaelectric, of Dublin, Ireland, to form Gaelectric Northwest. The joint venture, which is based in Clarkston, wants to develop projects in Washington, Oregon, and Idaho.

"We're young enough and, I guess, wild enough, to get in on the cutting edge of this," says the 51-year-old Laney, who's CEO of Gaelectric Northwest. "We're really excited. Everything is in the process of change" in energy development.

AirDynamics had been working for some time to develop a proposed 200-megawatt wind-turbine farm on Lincton Ridge in northeastern Oregon when two multinational companies offered to buy the project last year, Laney says.

"It would have been a lucrative deal," he says, "but my wife and I believe in the long term. We like to look down the road 10 years. We wanted to develop the project and run it. We've entered into a relationship with the land owners."

Then, AirDynamics was approached by Gaelectric, which Laney and his partners knew had been working to develop wind-farm projects in Montana.

"Gaelectric was different," Laney says. "They had Dolmen Securities, a major financial house in Dublin, at the table. Here in the states, all the big financial people are not up to speed on this. They're working on it, but they're not there yet." Last July, Dolmen raised 30 million euros through a financing for Gaelectric's expansion into the U.S., where it has offices in Washington, D.C., and Great Falls, Mont.

Laney found Gaelectric's leaders, including Managing Director Brendan McGrath, to be likable, which he says was important if he was going to work with another company. He also found that Gaelectric, which describes itself as a group of companies, employs staff members who previously had worked for Renewable Energy Systems and Airtricity, major British and Irish developers, respectively, of billions of dollars worth of wind-powered generation in Europe.

"You have people that you like. You have a lot of people on staff who have built projects. Then you have the financial house," Laney says. "The company is run very much like a small business. It's real easy to get a decision" on whether to become involved in a project.

When the joint venture was announced, Gaelectric said it had eight projects in Ireland that had received regulatory approval, planned to complete its first operational wind-turbine farm there in the second quarter of 2009, and had another 12 projects in different stages of planning and permitting. It also said it controlled a portfolio of U.S. projects that could generate a combined 1,700 megawatts of electricity. One megawatt of power is enough to meet the needs of 750 homes.

"That number has dramatically increased since that press release," Laney says. "They were working on one project that was half that big alone." Of the total portfolio of projects, 500 megawatts were AirDynamics projects.

In the announcement, the joint venture said it's "developing a pipeline (of projects) of up to 4,000 megawatts over five years." The Pacific Northwest's total average electricity consumption is about 21,000 megawatts.

Laney estimates the cost of the joint venture's Lincton Ridge project at about $400 million and says construction of it could get under way in 18 to 24 months and would take 90 to 180 days, "based on the availability of skilled labor, management, and equipment."

Last week, Dave Richards, who with his wife, Marci, founded AirDynamics with the Laneys, met with Oregon state officials in Portland as Gaelectric Northwest began efforts to obtain permits for the Lincton Ridge project, which is about eight miles southwest of Milton-Freewater, Ore., Laney says.

An anemometer at Lincton Ridge already is capturing wind readings, which are beamed via satellite to Gaelectric's technical office in Coleraine, Ireland, for analysis by the Irish company's experts, says Laney.

Gaelectric Northwest is closer to launching construction of a 10-megawatt wind-power project in Umatilla County, Oregon, that it plans to develop with Chris Bodewig, a Pilot Rock-area rancher who wanted to develop generation on his family's land, Laney says.

"We're fairly close to construction on that," he says. "He's done wildlife studies. The raptor and avian studies are done. So is the wind study."

Bodewig already had put an anemometer up on the family's property when Laney met him during a visit to Umatilla County, and Laney and an engineer went to the site right after they met Bodewig. Later, Laney and Bodewig hammered out the details of a basic agreement at a kitchen table, then followed up with formal agreements. McGrath attended a meeting at Pendleton, Ore., at which the agreements were signed, and he journeys to Clarkston for Gaelectric Northwest board meetings every 60 days, Laney says.

"Right now, one of our business models is to do exactly what we did with Chris Bodewig," Laney says. "There are a lot of individuals all over the country who are interested in alternative energy. What's really exciting to me is when I can go to a person like Chris and provide them with the missing piece for a project and help them to realize their dream."

That missing piece can be construction experience, perhaps, or financing, he says. Laney and his wife founded one construction company, and he has worked for others. "Virtually all my life, I've been in construction," Laney says. He says Gaelectric Northwest can provide financing to developers of small projects thanks to Gaelectric's relationship with Dolmen Securities.

"I'm currently in negotiations with a group in Colorado and a group in Nebraska," both of which are interested in developing wind-power projects, Laney says.

Fewer studies are required to obtain permits for smaller projects, which fall under the Public Utility Regulatory Policy Act (PURPA), than for big ones, Laney says. PURPA, a federal law, requires utilities to buy power from non-utility generators of relatively small amounts of electricity at a price that's equivalent to what their cost would be in supplying the power themselves.

Gaelectric Northwest also is looking to develop more large projects such as the one it has proposed on Lincton Ridge. For example, Laney says, the company "put a proposal in" on Avista Corp.'s planned 50-megawatt wind-power project near Reardan, Wash. Avista spokesman Hugh Imhof says Laney has talked with the Spokane utility, but Avista has no agreements in place with Gaelectric Northwest.

The Irish company has been in the U.S. for three years, working to find and develop wind-power projects, primarily in Montana. In July, McGrath told the Irish Times newspaper that Montana is "a vast area with lots of wind—it is like Saudi Arabia was in the 1920s."

Judy Chapman, a Billings, Mont.-based contract marketing and public relations agent for Gaelectric, says the Irish group has four projects in Montana for which it controls lease rights.

"A lot of these places, they're still monitoring to see if they're viable," she says. The monitoring includes gathering data on wind speeds and patterns. She adds, "That usually goes on for a year before any ground is broken."

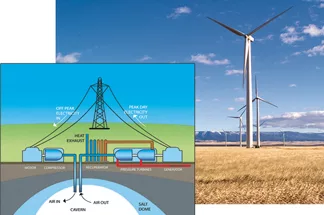

In a meeting at the Montana state capitol in Helena in October, Gaelectric representatives outlined a compressed-air technology that they said might enable wind-power developers to store energy produced by their turbines, which would make wind power more marketable.

The Billings Gazette reported that Keith McGrane, head of offshore energy and electricity storage for Gaelectric, explained that the wind blows stronger at night than during the day, and demand for power is lower then. Wind turbines can generate electricity at such "off-peak" times to run air compressors that would compress air so it could be stored under pressure in large underground caverns. During periods of heavy demand for electricity, the compressed air could be withdrawn, and with a natural-gas fired turbine could generate low-cost power.

Because the air is under pressure when it's released, it "supercharges the turbine" much like blowing air on a fire causes the fire to burn hotter, Laney says. He adds, "No one has perfected the technology before. No one has found the right combination to release that energy—I'd say until now." He says that encouraging research and development work is under way on the technology. Gaelectric says the technology could balance an electrical system that distributes power generated with wind, which, of course, is an intermittent resource because the wind doesn't blow all the time.

Chapman says Gaelectric has looked at 90 "prospect" properties in Montana for wind-power storage, has found five sites that it judged to be "viable," and is doing computer modeling at two sites to determine whether a compressed-air plant would work at those locations. At the presentation in Helena, McGrane said Gaelectric isn't releasing the locations of the two properties, but estimates that it would cost roughly $105 million to develop a 140-megawatt compressed-air energy-storage facility.

Related Articles

_c.webp?t=1763626051)

_web.webp?t=1764835652)