Home » 'Hair-popping sharp'

'Hair-popping sharp'

January 29, 2009

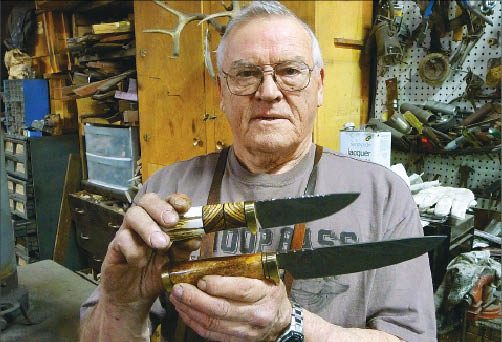

Ray Rantanen breaks into excited laughter as he describes how microscopic cutting teeth form on the blades of the knives he crafts when his customers begin to use them—actually making the carefully honed edges sharper with use.

Simply put, Rantanen gets a kick out of knives that work really well.

Rantanen owns Iron Anvil Forge, which he founded in Colorado in 1976, but now operates in a 1,600-square-foot garage-like building a few steps outside his log home near Spirit Lake, Idaho. There, Rantanen makes more than 200 high-end knives a year, along with a host of other sharp weapons and tools—from chisels to spears.

He sells them directly to consumers throughout the U.S. and abroad, mostly over the Internet.

The 67-year-old former aerospace scientist and NASA contractor—who holds a doctorate in physics from Washington State University—touts his knives as "hair-popping sharp," meaning that if you slide the blade along your arm, the hairs along its path just "pop off."

As for the notion that Rantanen's knives get sharper with use, he explains it this way: The microscopic teeth begin to reveal themselves as one of the three types of steel he combines in the blades of his Damascus steel knives wears down sooner than the other two—just as he intends—leaving the others to create a saw-like edge. To illustrate, Rantanen holds the palms of his powerful blacksmith hands together, and uses the tips of his fingers to simulate a saw-tooth blade. Again, he begins to laugh.

Rantanen's graduate work at WSU involved the study of the effects high temperatures have on metals, and he says his schooling helped him understand the intricacies of forging and tempering iron and steel. He is, however, a self-taught knife maker. He says he's never seen a knife made, except by his own hands, and has never been to a knife show.

"I took no formal training," Rantanen says. "I did a lot of experimentation. I did everything wrong once, and then I learned from that."

In his production building, a blazing wood stove heats his work area, which is in a state of organized chaos. It may appear messy to visitors, he says, but everything is always right where he left it, and therefore right where he needs it. Boxes, buckets, and drawers overflow with horns, antlers, bones, and exotic and rare woods, all to be used in the handles on his knives. Old chainsaw bars, long saw-blade sections from lumber mills, piles of railroad spikes and smaller mine spikes, and horseshoes are at hand as well—raw materials for the blades he forges by hand.

Rantanen makes about 220 to 230 knives per year, generating about $60,000 to $70,000 in annual sales, he says. All of his sales are made via his Web site, at www.raysknives.netfirms.com, or via mail order from previous customers. The majority of his customers live on the East Coast or in the South, but he also sells knives overseas, to customers in Germany, France, Japan, and Singapore most often, he says. He doesn't supply any stores.

"Performance first, and beauty second," Rantanen says of his knives.

Yet his knives don't lack beauty. About 75 percent of his sales are of his Damascus steel knives, whose blades feature distinctive patterns of light-colored waves on a dark background. Damascus, Syria, was where such patterns first appeared in steel blades in the 12th century.

Rantanen forms his Damascus blades from layers of what are called O-1 tool steel, S-2 shock steel (used for jackhammer bits), and mild steel. The blades start with seven layers of steel—four layers of one-eighth inch thick mild, two layers of three-eighths inch thick S-2, and one layer of three-eighths inch thick O-1—but are stretched by hammering and folding until the thickness of the blade is about 224 layers. The blades end up roughly one-fourth to one-eighth inch thick, with the thickness of a typical hunting knife, he says.

Prices for Rantanen's Damascus steel knives range from $125 to $1,200, largely depending on the material used for each knife's handle and the length of blade. His blade lengths range from two inches to 10, he says.

Handle materials can include 15,000-year-old mammoth tooth or ivory, antelope horn from Africa, deer and elk antler, exotic wood, and even fossilized walrus penile bone, he says. Many of the knives have both hand guards and caps made of brass, with some caps, which are butts of knives, resembling a hawk's head.

The knives Rantanen makes from old horseshoes or high-carbon railroad spikes range in price from $90 to $180, he says. The sale of those two types of knives make up the remainder of his core sales, he says. Each knife is different, Rantanen says, and the quality of each knife being unique helps make them more valuable, and ultimately boosts sales. Though two may be similar and have the same patterns, they're never exactly the same, he says.

Rantanen has been blacksmithing since 1974, and has specialized in knives since 1986. He's taught blacksmith classes and demonstrated at festivals.

He doesn't just make knives, though. Rantanen, who is part Cree Indian, carves and sells totem poles and makes tomahawks, and some of the tomahawks are adorned with animal fur or a coyote skull. He also makes leather products, including sheaths for the knives he sells, as well as chisels and other carving tools, plus primitive war clubs, bone knives, lances, spears and swords. He makes coat racks, letter openers, fillet knives, kitchen knives, barbeque tools, and axes.

Rantanen says making knives is a creative outlet for him and allows him to make a comfortable living in the process, with no pressure—and he's able to stay close to home. The positive response from customers motivates him to continue crafting knives.

"It's a creative outlet that I need," he says. "I've got to create something, and it's got to be something that sells."

He uses a propane forge and what's called a 50-pound trip hammer, with which he hammers away rapidly on the glowing steel with hundreds of pounds of force to draw the steel out longer. His trip hammer is adorned with a 1909 patent date and a no-wimps sign. The trip hammer—which he calls his "dumb apprentice," because it doesn't eat and never asks to be compensated—speeds the blade-making process, he says.

"Without it, I'd be out of business," he says, adding that he's tried real apprentices, but that didn't work with his flexible schedule, which can be interrupted if the fish are heard to be biting.

Rantanen and his wife, Ranae, both of whom are Inland Northwest natives—he was born in Kellogg, Idaho, and she was born in Spokane—moved in 1992, to North Idaho, where they still have relatives. They both went to school in Spokane, he says. Rantanen was living in Colorado when he began blacksmithing in 1974. At the time, he was employed by an aerospace company. In the past, he also did contract work for NASA, including analysis of the complex interactions between spacecraft and their orbit environment to determine if they would degrade in space.

He says he plans to stay in business here selling knives for about 10 more years, though he may focus on making more expensive versions in the years ahead, and fewer of the less expensive ones. On his Web site, he says, "If I don't keep improving, or by chance I make a perfect knife—I will quit."

Latest News

Related Articles

_web.jpg?1729753270)