Home » Higher rates fund upgrades, Avista says

Higher rates fund upgrades, Avista says

Top executives contend return must be sufficent to keep good credit rating

March 12, 2009

Avista Corp., stung by criticism of its latest rate-increase request, says it must raise its electric and natural gas rates to catch up on capital investment in its infrastructure, to provide sufficient return to investors to maintain investment-grade status, and to avoid exorbitant borrowing costs.

In a meeting with the Journal's editorial board on Feb. 18, the day Avista reported 2008 earnings of $73.6 million, the company's top managers lamented that even though Avista's annual earnings had risen by 89 percent, its stock price fell by 44 cents that day.

"We're barely investment grade now," Scott Morris, Avista's chairman, president, and CEO said. "If we didn't ask for rate increases, we'd undoubtedly be put into non-investment grade."

The company, which periodically sells bonds to raise capital to finance its activities, currently is rated at bbb-, the lowest of seven investment-grade ratings given to U.S. regulated electric utilities, Morris says. He says if the company were to slip into non-investment grade status, the interest it pays on the bonds it sells, which probably would be 8 percent to 10 percent if Avista sold bonds in today's adverse markets, could soar to 15 percent.

The company is spending $200 million annually on capital investments to upgrade its infrastructure and will continue to do so, following long periods when its capital spending lagged, Morris says.

"As long as we have large expenditures to bring energy to our customers, there will be pressure on rates," Morris says. While the company tries to keep those expenditures reasonable, "for the next several years it appears we will need to ask for rate relief," he says.

Asked how the company weighed whether the rate increases it sought could result in "rate shock," or a slowing of the regional economy because ratepayers would have difficulty absorbing the increases, Morris says, "We are always concerned about impacts on the economy and customers when we ask for rate increases. That is why we strive to keep those increases as low as possible."

Yet, if Avista doesn't recover its costs, its credit rating will slip, and it will lose investors, which would increase costs and create an even greater rate impact, Morris says. "It really is a balancing act for us."

In the 1980s, after the Washington Public Power Supply System defaulted on billions of dollars worth of bonds when cost overruns derailed its construction of three nuclear power plants, Avista, then named Washington Water Power Co., took a "crippling" write-down on its investment in one of the plants, Morris says.

"WPPSS went bankrupt, and our company almost went under," he says. "We cut our capital budget to save the company."

When federal and state officials debated deregulation of the utility industry in the 1990s, utilities cut back capital expenditures "to avoid stranded investment" they might have lost if ordered to divest parts of their businesses, Morris says.

The U.S. Energy Policy Act of 2005, enacted after a dramatic flurry of brownouts darkened much of the East, mandated more stringent reliability standards for electric utilities' transmission systems, Morris says.

"That's fine, but it comes at a cost," he says.

Also, new requirements to capture mercury from the emissions of coal-fired generating plants have added $3 million a year to Avista's costs, the company says. Morris says other environmental requirements, including Initiative 937, which requires utilities to meet certain levels of their load in Washington state with renewable power, also will add costs.

On Jan. 23, Avista sought a net electric rate increase of 8.6 percent in Washington, after deducting reduced power-cost surcharges, to cover rising power-purchasing and -generating costs, infrastructure investments, and compliance with environmental and legal requirements. It also sought a 2.4 percent natural gas rate increase.

Yet, with the economy here slowing so fast that 3,400 fewer people were employed in January than in the year-earlier month, the rate-increase request sparked a backlash. On Feb. 7, roughly 115 people gathered outside Avista's headquarters at 1411 E. Mission to protest their much higher bills plus rate hikes effective Jan. 1 of 9.1 percent for electric customers and 2.4 percent for natural gas customers.

Morris noted the weather was so bad in late December the region almost caught up with its normal snowpack, which was at 30 percent of normal at mid-month. On 14 days in December, the high temperature was below freezing, and on three or four days, the average temperature was 0, Morris says.

Because the autumn had been mild, and because many customers had an unusually long 34-day billing cycle, bills for December's usage shot up markedly from the previous month's, Morris says. Also, he says, the company estimated more bills than usual because deep snow kept meter readers from reaching meters.

The bills that people protested didn't even reflect the Jan. 1 rate increases.

"When people were protesting and saying, 'My bill doubled,' we hadn't raised anybody's rates yet. We need to tell our customers, 'Yes, your bill did go up, but did your bill go up because of a rate increase? No.'"

The best way for customers to keep rates low is to conserve energy, Morris says. Still, he acknowledges, "The customers that are the most challenged are renters, living in older residences that have baseboard heat and aren't weatherized." Those customers often have little money to spend on energy conservation, he says.

Even though Avista's Washington and Idaho electricity customers far exceeded the company's goals in 2008 for reducing electricity consumption through conservation improvements covered by the company's rebate and incentive programs, residential electricity sales grew by 5 percent in 2008, Morris says. He says that in addition to economic growth, the increase is being driven by power-hungry new items in the home such as flat-screen TVs and other devices. "When I grew up, I didn't have air conditioning in my house, and neither did any house on our block," but it's common now, he says.

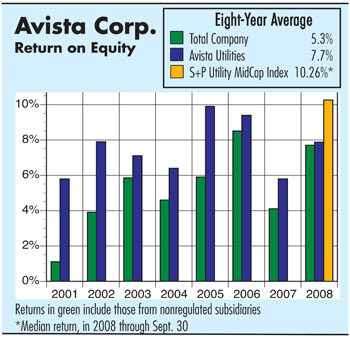

While Avista Corp.'s profits shot up last year, it still made less money than it did in 2006, and for the next two or three years, it's likely to earn rates of return on equity of only about 8 percent a year, well below its state-authorized rate of return of 10.2 percent, Morris says. At rate of return of 7.17 percent through the nine months ended Sept. 30, Avista trailed the S&P Utility MidCap Index of 10.26 percent, he says. The company has asked the state to increase its approved rate of return to 11 percent.

Meanwhile, Avista faces a number of challenging developments, Morris says.

Fifty-year contracts under which the company bought power at a dirt-cheap 1.5 cents per kilowatt-hour from Priest Rapids and Wanapum dams on the mid-Columbia River either have expired or will expire in September, Morris says. Those contracts have been renewed, but the new contracts call for Avista to pay market rates for the power, says Avista Utilities President Dennis Vermillion, who also participated in the editorial board session. Avista had been obtaining an average of 61 megawatts of power from the two dams under the old contracts, but that will be roughly halved under the new contracts. One megawatt of power is enough to serve 750 homes.

In 2011, a contract for power generated at Rocky Reach Dam on the mid-Columbia will expire, and in 2018 a contract for power from Wells Dam will expire, Avista says. Under those contracts, which haven't been renewed thus far, Avista pays roughly 1 cent a kilowatt-hour for electricity, it says. Avista has been receiving an average of 32 megawatts of power from the two dams, giving it an average of 93 megawatts from all four of the mid-Columbia impoundments. By comparison, the company generates an average of 125 megawatts of power at all six of its Spokane River power plants combined.

In January next year, the company will get back power production from the 280-megawatt Lancaster Road natural gas-fired plant near Rathdrum that its longtime Avista Power subsidiary and a partner built years ago. The plant later was sold to Avista Power's partner, although another Avista subsidiary already had contracted out the supply from the plant for several years. Vermillion says Avista will pay market rates for that power.

Meanwhile, a property-tax break granted by the state of Oregon for Avista's development of its Coyote Springs 2 natural gas-generating plant near Boardman, Ore., is expiring, Morris says. Avista spokesman Hugh Imhof says the company had been paying property taxes of $143,000 a year on the plant because of the break. "As of July 1, we estimate it will go to $3.1 million," he says.

Avista, which had put off building its first wind-power farm until 2012, could benefit from an extension in the recent federal stimulus bill of a production tax credit on wind power projects. That legislation will give wind-power generators a 10-year income-tax credit of 2.1 cents for each kilowatt-hour of electricity they generate at a wind facility developed by 2013.

Avista has spent $26 million to relicense its Spokane River dams, although that's far lower than the $105 million Idaho Power Co. has spent thus far to relicense its Hells Canyon complex of three dams on the Snake River, with that relicensing yet to be completed, or the $40 million the Grant County Public Utility District spent to relicense its Priest Rapids and Wanapum dams, an effort it completed last year, Morris says.

In addition, Morris contends Avista has been careful with its general and administrative expenses, saying that just 12 cents of each $1 electric ratepayers spend goes to such expenses.

"You could literally lay off the entire administrative staff and not move rates very much," he says. "We haven't added bodies. We've been trying to really mind the store."

Latest News

Related Articles

![Brad head shot[1] web](https://www.spokanejournal.com/ext/resources/2025/03/10/thumb/Brad-Head-Shot[1]_web.jpg?1741642753)