Home » Avista, tribal pact said one for the books

Avista, tribal pact said one for the books

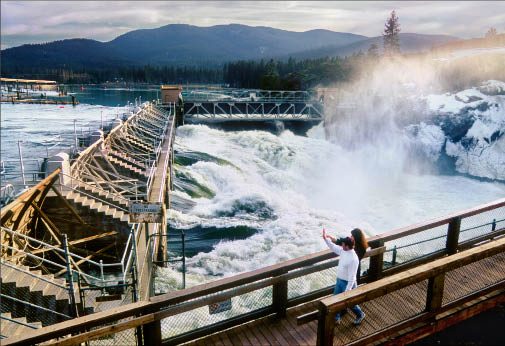

Agreements with Coeur d'Alenes, others call for $373 million in mitigation outlays

April 23, 2009

When Avista Corp. agreed to pay $168 million to the Coeur d'Alene Tribe for past and future impacts of Post Falls Dam on the tribe and its lands, the amount captured headlines. Yet, there's much more to the story.

The deal was hammered out with the help of a senior federal appeals court judge, and it spells out that Avista will spend an additional $205 million in non-tribal related outlays under its pending 50-year federal license to operate five Spokane River dams.

The company expects to have that license, sought from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), soon, says Bruce Howard, who managed the relicensing project for Avista.

"We have other requirements that FERC is adding," says Howard, now director of environmental affairs. "We won't know until we receive the final license order." He says the company hopes its agreements with the tribe will address many issues adequately.

Those agreements probably total 200 pages in length, says William Schroeder, a partner with Paine Hamblen LLP, of Spokane, and Avista's lead counsel in the case, but "maybe 100 banker boxes" of documents have been accumulated in the relicensing. Howard A. Funke, an attorney with Howard Funke & Associates, of Coeur d'Alene, and the tribe's outside counsel, says, "There's 70,000 pages of documents involved."

Schroeder; Funke; Eric Van Orden, the tribe's in-house counsel; tribal legal assistant Jack Ross; Marian Durkin, Avista's general counsel; David Meyer, Avista's legal vice president; and lawyers from the U.S. Department of the Interior worked on the agreements.

"Over the course of six months or so, I probably worked on it full time," says Schroeder.

William C. Canby Jr., a senior judge on the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, became involved in the relicensing in 2005 when the two sides arranged to obtain an advisory opinion from him, and worked on the settlement documents. The University of Minnesota Law Review, published by Canby's alma mater, says the judge is one of the nation's premier experts on Indian law.

Says Schroeder, "I don't think there's been a case like this anywhere in the U.S." in terms of its complexity and the breadth of the historical issues involved. "I think there will be law review articles written about this and how the parties reached agreement after 100 years of conflict." Avista's Howard says, "FERC had told me, 'This is the most complicated relicensing setting we've ever seen.'"

Howard believes the settlement is a good deal "in a couple of ways. One, we analyzed, multiple times over the years, what our risks were." He says the company faced many millions of dollars in financial liabilities if it didn't secure agreements to reduce its risks. Also, he says, "We got 50 years of certainty for the communities around Lake Coeur d'Alene to protect resources that the vast majority of our customers enjoy every day."

In addition to the $68 million Avista will pay the tribe for reservoir storage, it has agreed to pay into a trust fund $2 million a year during the 50-year license to cover mitigation for the impacts on the tribe's natural and cultural resources by its dams. That $100 million in outlays would bring the total for tribal-related issues to $168 million.

Avista and the tribe will manage the trust fund jointly, and the U.S. Department of the Interior will be involved in approving work plans to address shoreline erosion control; wetland restoration, replacement, and maintenance; water quality monitoring; aquatic management; and protection of cultural resources.

"The tribe has a very talented staff and will be able to do a lot of that work," although other contractors will be involved, too, Howard says.

The $205 million in non-tribal related spending will cover Avista's obligations under agreements reached with the states of Washington and Idaho and numerous interest groups, Howard says.

"We had gone through four years of a stakeholder collaboration process with over 200 different entities and over 600 individuals," he says. The company signed agreements with every group on every issue but one—the Sierra Club's contention that water diversions proposed to improve the aesthetics of Spokane Falls were inadequate.

FERC is requiring Avista to draw up a sediment management plan, an aquatic weed management plan, an information and education plan, and a comprehensive recreation plan. The agreements cover numerous other things.

The legal history in the case is extensive, and even today both sides don't agree on all of it. Funke says that Washington Water Power Co., as Avista then was named, acquired the Post Falls Dam site in 1906 and built the dam without permission. "They needed that power to deliver it up to the Silver Valley. Mining was booming in the Silver Valley."

Howard says that WWP acquired the rights to flood land from the successors of Frederick Post, who reached agreement with the tribe in 1871 to develop hydroelectric power in the Post Falls area. The two sides "agreed to somewhat of a timeline" of events, but not necessarily to one another's interpretation of them, he says. "Like a lot of settlements, you set aside a lot of things."

When the state of Idaho was created in 1890, it had claimed ownership to Lake Coeur d'Alene. In 1972, the tribe and the Interior Department asserted that the Coeur d'Alenes owned all or part of the lake. In 1980, an administrative law judge ruled that the state owned the lake, but FERC reversed that decision three years later, then later determined it lacked jurisdiction to make that decision. In 1994, the U.S. government sued the state on behalf of the tribe. A U.S. District Court ruled in 1998 that the tribe owned part of the lake, and the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed that ruling, 5-4, in 2001.

In 2002, Avista began the formal Spokane River relicensing process. It had begun meeting with the tribe in 1999 to identify and seek resolution of issues. The two sides had held many meetings.

Later, the tribe and Avista presented their cases to Canby.

"We put on expert testimony," Howard says. "It was like a full federal trial. We asked him, 'Is there a trespass?' He said, 'There is a trespass. It goes back to 1906 or 1907. There are some gray areas.'" The judge suggested it would be better if he didn't write an opinion on damages, because that likely would have sparked a court battle, Howard says. Canby's work "showed us points of disagreement, and the two sides set to work on them with a mediator." The judge was involved in several meetings.

In July 2006, Interior proposed conditions for relicensing. Avista offered alternatives and requested a hearing. In December, an administrative law judge held a hearing, and in May 2007, Interior issued revised mandatory conditions.

Negotiations continued, and in December 2007, the tribe and Avista, with Canby and the mediator, reached a settlement in principle. A year later, the settlement agreements, on water storage, relicensing, transmission line rights-of-way, water rights, and tribal taxation, were signed.

Not long after the settlement was reached, Washington state public counsel Simon ffitch appealed to Thurston County Superior Court a portion of the Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission's approval of it. The WUTC had rejected a contention by ffitch and others that allowing Avista to obtain $39 million from ratepayers to pay for past reservoir storage violated a legal doctrine against "retroactive ratemaking," which blocks utilities from obtaining money from ratepayers to cover expenses from the past.

The WUTC had said, "Avista operated the project with authority from the entity it reasonably believed was the rightful owner, the state of Idaho." It added, "Until Avista reached a settlement earlier this year, it had no obligation to the tribe."

Says ffitch, "We disagree with the conclusion. There is no dispute about the facts." He says the court on May 1 will schedule a briefing and arguments in the case.

Avista Chairman, President, and CEO Scott Morris rejects that idea that recovering the $39 million from ratepayers would amount to retroactive ratemaking. "We didn't know that there was any law that applied until 2001," he says.

Of the settlement effort, Morris says that the tribe and Avista were far apart at first, but the Coeur d'Alenes were just "exercising their rights. It was a tough process, but in the end, it was fair. We came out of it with a good working relationship. Chief Allan and I shook hands at the end."

Tribal Chairman Chief Allan says, "This agreement finally compensates the tribe for Avista's use of tribal lands to bring power generation to the region at the turn of the 20th century. It also provides a new foundation for the tribe and Avista to work cooperatively together."

Latest News

Related Articles