Sacred Heart ponders next move

Expansion plans in flux after state's denial; rivals opposed additional beds

Providence Sacred Heart Medical Center & Children's Hospital was expected to decide by a deadline late this week whether to appeal the Washington state Department of Health's recent denial of its certificate of need application for 152 more acute-care beds.

Also, a review of the state's decision shows that Sacred Heart's competitor, Community Health Systems Inc., which operates Deaconess and Valley hospitals, opposed the expansion, as did Premera Blue Cross and a doctor's group. Sacred Heart contended, though, that CHS was trying to undermine, or sabotage, its application by improperly inflating the number of acute-care beds available at its facilities here "at the last possible moment in an effort to game the bed count."

The state's decision pertained to a roughly $85 million portion of a planned $175 million expansion project at Sacred Heart. If it stands, though, it will force hospital officials to re-evaluate the remaining pieces of that project, including how, when, and perhaps even whether it will proceed with them.

"It was a very integrated project. The sequencing mattered. The timing mattered," so the entire capital plan would have to be reviewed, says Sharon Fairchild, vice president of marketing and planning for Providence Health Care, which operates Sacred Heart.

She notes, for example, that a major emergency department expansion planned as part of the project, but not subject to the state certificate of need process, is at least partly dependent on having those additional acute-care beds so the hospital could place patients in them following their emergency-room care.

The hospital had hoped to begin construction late this year or early next year. For now, though, Fairchild says, the hospital's focus still is on how to respond to the state's denial of its application.

Even if Sacred Heart filed a request for reconsideration or a request for an adjudicative appeal hearing by the July 16 deadline and a hearing were granted, the chances of the ruling being overturned appear small. Janis Sigman, director of the agency's certificate of need program, says applicants appealed one-third of 127 certificate of need decisions entered by the agency between 2000 and 2005, and just two of the appeals were successful.

For large hospital expansion projects, Sigman says, "It's fairly common that they are in phases, and we typically will approve a phase," but perhaps not additional proposed phases.

In Sacred Heart's case, though, although the state approved a certificate of need for 21 intermediate-care nursery beds, it denied entirely the request for additional adult acute-care beds. Sacred Heart had proposed adding the 152 beds in five phases beginning in 2011 and extending through 2015, but Bart Eggen, a Department of Health executive manager, says the hospital didn't break out the five phases in a way that would have allowed the agency to consider them separately. "It was pretty much next to all or nothing," he says.

It's unclear whether the agency would have approved an initial smaller phase, anyway, he says, because, "The numbers alone looked as if there's considerable capacity in Spokane for years to come."

Sacred Heart continues to disagree with the state agency on that point.

"We still have capacity constraints today in our critical-care beds, and we know volumes are going to go up. Trauma volumes will shift to Sacred Heart" now that Deaconess has decided to discontinue providing high-level trauma care, Fairchild says.

She says Sacred Heart averaged 92 percent occupancy in its intensive-care unit beds during the first half of this year, which is "very high" by industry norms.

In its 41-page decision rendered on June 19, though, the state rejected two of Sacred Heart's three methods for estimating future acute-care bed needs here and ruled that the third method was faulty, understating the current surplus by more than 100 beds and overstating the need for more beds in 2015 by a similar margin.

In determining the number of acute-care beds currently available here and in calculating community need, the agency said Sacred Heart improperly factored 72 beds at St. Luke's Rehabilitation Center into its equations and used different population projections than the state applied. It also said that Sacred Heart underestimated the number of acute-care beds at Deaconess Medical Center, Valley Hospital & Medical Center, and Providence Holy Family Hospital by 64, 30, and nine beds respectively. Based on those differences, Sacred Heart's estimate put the Spokane area's total acute-care capacity—not including St. Luke's—at 1,096 beds, which was well below the state's figure of 1,199 beds.

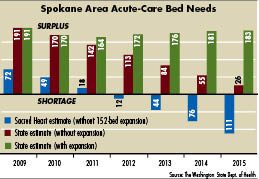

Using a formula that looks at the projected increase in patient days experienced by hospitals here, Sacred Heart's calculations put the 2009 overall surplus at 72 acute-care beds, but estimated that surplus would be wiped out by 2011 and that the area would need 12 more beds by 2012, 44 more by 2013, 76 more by 2014, and 111 by 2015.

The Department of Health said, though, that its calculations showed the Spokane area having a 191-bed surplus this year, and it projected that a surplus would continue—without the expansion project—throughout the seven-year planning period used in the application. Its calculations showed that surplus dwindling to 26 beds in 2015. The department calculated that if Sacred Heart's proposed expansion were approved in its entirety and developed as planned, the surplus would dip to 164 beds in 2011, then rise gradually to 183 beds by 2015.

The agency noted in its decision that it had received letters of support for the project from state and federal elected officials, various local physician groups, and trade unions, plus regional hospitals and health districts. All of the letters, it said, expressed concern about overcrowding at Sacred Heart, long waits in the emergency room, and population growth.

It said, though, that it also received a number of letters of opposition, including from the CEOs of Deaconess and Valley Hospital, both now owned by Community Health Systems Inc., a competitor to Providence, and also from big regional health insurer Premera Blue Cross and a physician group here.

In their lengthy joint response to Sacred Heart's application, Deaconess' Tim Hingtgen and Valley Hospital's Dennis Barts asserted that Sacred Heart was overstating its occupancy rate and the area's projected population growth and that a correct accounting of the current supply negates any need for more acute-care beds.

Considering the timing of the application, close on the heels of CHS's acquisition of Deaconess and Valley, they further said, "We must conclude that this SHMC project is, at its core, an attempt to thwart efforts to rebuild and stabilize Deaconess and Valley Hospitals."

The two hospital executives said, "We believe that the department has an obligation, both to our newly acquired hospitals, but more importantly to the Spokane County community, to provide our hospitals with a chance to achieve and sustain financial health. Doing so requires that projects predicated on competition, and not on documented need, be avoided."

Sacred Heart countered that Deaconess was trying to sabotage its application by providing the agency inaccurate and misleading acute-care bed figures "in an effort to increase the bed count for the region and eliminate any projected need."

In a 160-page rebuttal to project critics, Elaine Couture, Sacred Heart's chief operating officer, said Sacred Heart provides services that aren't available elsewhere here, a factor that bed need calculations should take into account. For example, she said, "Valley receives almost no transfers from other hospitals because it does not provide the specialty tertiary care provided by Sacred Heart. An empty bed at Valley, therefore, is not the same as a bed that's needed at Sacred Heart."

She also said the project is estimated to save the hospital more than $54 million in the first few years after completion due to efficiencies gained through economies of scale.

The letter from Premera, the decision said, encouraged the department "to carefully consider the alternative scenarios in determining the need for this project at the scope included in the application. Unneeded beds add cost to a health care system that is already financially strained."

The physician group, it said, maintained that Deaconess has both unused capacity and shelled space that could be made operational quickly, and it noted that CHS has committed to invest $100 million in capital projects at Deaconess and Valley Hospital over five years.

The department said in its conclusion that although the proposed Sacred Heart expansion is supported by many in the community, the Spokane area's bed capacity at alternate hospitals and the agency's calculations don't support the project.

It also rejected the project separately based on financial criteria, saying that Sacred Heart's miscalculations of need for the additional rooms and the added surplus the project would create might reduce its anticipated revenues from the expansion. It concluded that the hospital "would not be able to meet its short- and long-term costs of the project with an additional 152 acute-care beds relying on the projected patient days" it incorporated into its financial ratios.

Related Articles