The pension-401(k) hybrid

New retirement tool will combine benefits of both types, is geared for small business

A hybrid retirement funding option that melds an employer-funded pension and an employee-funded tax-deferred account into a single plan will be available to small businesses starting Jan. 1, 2010, but it's getting lukewarm advance reviews from some retirement planners here.

The new type of plan, for companies with two to 500 employees, is authorized by the federal Pension Protection Act of 2006 to start in January. Called a DB(k) plan, it gets its name from both a conventional defined-benefit plan, or pension, and a 401(k), because it has elements of both types of plans.

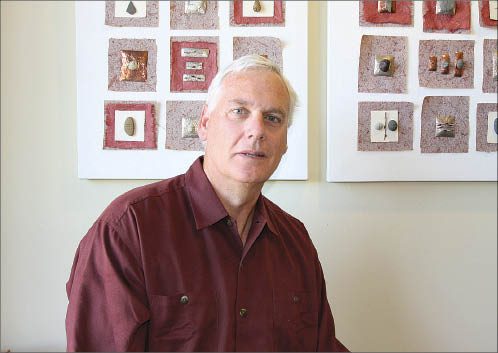

Mark Powers, managing principal in NAS Pension Consulting Inc., of Spokane, says he believes a DB(k) plan is a good idea because it's intended to make it easier for small businesses to offer both a pension and a 401(k) in one plan.

"I would hope it gets more employers thinking about offering defined benefits," Powers says.

The plan would include an automatic deduction of 4 percent of an employee's income that would go into a 401(k) account, although the employee could opt out or change the contribution rate. The employer would be required to match at least 50 percent of the employee's contributions, up to 2 percent of an employee's income.

The participating employer also would be required to provide a minimum defined benefit of 1 percent of the employee's average pay earned by an employee during his or her last three years of work multiplied by the number of years the employee worked while enrolled in the plan, up to 20 years or 20 percent of final average pay.

"Supposedly, it would reduce complexity and require less administration" than two separate plans, Powers say. "It's still going to take significant administrative effort. That's good for people like me."

Some companies that currently offer combinations of two separate plans, however, might choose to continue to do so rather than opt to comply with the rules and regulations of a single combined plan, Powers says.

Clay Randall, a principal in Randall & Hurley Inc., of Spokane, says the DB(k) plan likely will be attractive to physicians' groups and professional firms that have steady income streams. "It will help them put away a lot of money for highly paid people," Randall says.

Companies with income levels that fluctuate with up and down economies, such as construction companies, likely wouldn't opt for the plan, he says.

John Kapek, who owns Pension Investment Services LLC, of Spokane, says a DB(k) plan would cost less to administer than separate defined-benefit and 401(k) plans with comparable combined benefits and contributions.

Kapek says, though, that some employers might prefer the flexibility of keeping 401(k) plans separate from pension plans. With separate plans, employers can adjust their voluntary 401(k) match as economic conditions—and company fortunes—change, he says.

"With a separate 401(k) plan, if employers don't want to make a match, they don't have to," Kapek says.

Employees who participate in a DB(k) plan would be vested fully in three years, meaning they would own 100 percent of the employer contributions.

Some employers might shy away from a plan with such a short vesting period, Kapek says.

Conventional retirement plans often have a five-year vesting period. "In most cases, when employers make significant contributions, they want to take advantage of vesting schedules as long they can," he says.

Randall says the upcoming DB(k) is fostering collaborative relationships between conventional pension planners and other financial service providers. Instead of having two separate plans, a client offering a DB(k) plan in effect might have two administrators who specialize in different arms of the same plan.

For instance, he says that Randall & Hurley, which specializes in defined-benefit plans, will work with Hartford Financial Services Group Inc., which will administer its clients' investment funds, to offer DB(k) plans.

"We don't handle investments ourselves," Randall says.

Powers describes DB(k) as a government push to encourage some employers to sponsor small pensions to supplement 401(k) retirement accounts.

"In a way, it's not anything that couldn't be done before," he says. "What's new is that employers would do it with one plan and one set of reporting requirements."

The 401(k) originally was conceived as a supplement to an employer-paid pension, but has become the primary means of retirement savings for many workers whose employers don't offer full pension plans.

A survey conducted early this year by the Transamerica Center for Retirement Studies, a nonprofit foundation funded by Transamerica Life Insurance Co., found that 21 percent of U.S. employers offer a company-funded defined-benefit pension plan.

The DB(k) concept could provide an employer with a competitive edge in attracting and retaining the best workers, Powers says.

"If the human-resource department makes a point that the employer is providing a healthy match to the employee's retirement and also a defined benefit of up to 20 percent of pay, it could be a recruiting tool," he says.

Theoretically, under the minimum employee and employer contributions to a DB(k) plan, a worker with a 35- to 40-year career would continue to receive close to the equivalent of 100 percent of their final three years' average pay after retiring, Powers says.

For employees who would start on a DB(k) plan in their 40s and 50s, the minimum employer and employee contributions into a DB(k) likely wouldn't provide the equivalent of full pay at retirement, but would be "meaningful and helpful," he says.

The Internal Revenue Service opened a public comment period about DB(k) plans last month, in part to hear pension planners' concerns prior to promulgating final rules for implementing the new plans.

"People like us who do the back-office computations and compliance work have thousands of questions," Powers says. "That's why new programs like this take so long to implement."

He says he's not seeing a lot of employer interest yet in the DB(k) plan.

A small fraction of employers who already offer separate defined-benefit and defined-contribution plans will find it worthwhile to combine two types of plans and reporting requirements into one, he says. An employer who's considering offering a defined-benefit plan might also want to look into DB(k), he says.

"I think there will be some appeal, but it will very limited," Powers says. "The whole concept will show the employer a combined plan is possible. It isn't going to be the new 401(k)."

Related Articles