Home » Bankers dig deep to prepay big premiums

Bankers dig deep to prepay big premiums

FDIC required institutions to send in check Dec. 30 for 2010, 2011, and 2012

March 25, 2010

Banks, already hit hard by sharply higher federal deposit insurance premiums earlier in 2009, were required to prepay three years worth of higher premiums on Dec. 30 last year, saddling them with a sharply higher expense for deposit insurance.

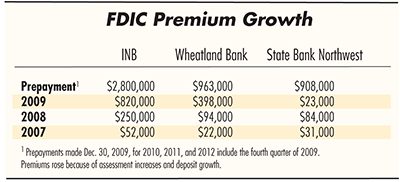

Inland Northwest Bank, of Spokane, wrote a check for more than $2.8 million to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. to cover its premiums for all of 2010, 2011, and 2012, plus the fourth quarter of 2009. The big check covered for 13 quarters an expense that had totaled just $52,000 for all of 2007.

"It's hit the balance sheet. It's hit our liquidity," says Randall L. Fewel, the bank's president and CEO. "It affects your cash balance, but not your profit and loss."

The FDIC said that the prepayment would allow it to strengthen the position of its Deposit Insurance Fund, which has fallen below required levels as it has been tapped to make depositors whole in the wake of bank failures across the U.S.

In the past, the fourth-quarter payment wasn't due until sometime during the first quarter of the following year, Fewel says.

"The sad part of the whole thing is in the good times, they should have been continuing to charge a normal amount to banks and build up their reserves, and they didn't do that," he says.

Andrew Gray, a Washington, D.C.-based spokesman for the FDIC, says, "As soon as Chairman (Shelia) Bair came in 2006 she moved forward with raising premiums" in 2007.

Inland Northwest Bank's expenses for deposit insurance rose to $250,000 in 2008, then shot up to $820,000 in 2009.

Wheatland Bank, of Spokane, prepaid $963,000 in deposit insurance premiums for 2010, 2011, and 2012, says Vicki Snider, the bank's controller.

Wheatland also paid at the end of the year $71,000 in premiums for the fourth quarter of 2009, bringing its total deposit insurance expense for 2009 to $398,000, up by more than 320 percent from $94,000 in 2008, Snider says. It paid $22,000 in 2007.

"We were still able to remain profitable because of our high net interest margin, high-quality loan portfolio, and relatively low loan losses," she says.

Greg Deckard, president and CEO of State Bank Northwest, says that Spokane bank paid $908,000 in its Dec. 30 check, "and I'm the smallest bank in Spokane." He adds, "There's a large amount of liquidity that's coming out of the banks and into the coffers of the FDIC."

Just the bank's expense for 2009 was, "at a minimum, triple what we paid two years ago," and the expense will be higher than normal for the foreseeable future, Deckard says. State Bank Northwest paid $31,000 for deposit insurance in 2007, $84,000 in 2008, and $231,000 in 2009.

Of course, the numbers get much higher at larger institutions. Sterling Savings Bank, which had $10.9 billion in assets at the end of 2009, said in its 10-K report that $29.4 million of its $30.6 million in insurance expense in 2009 "was related to FDIC coverage." Sterling had just $7.4 million in insurance expenses in 2008 and $3.8 million in such expenses in 2007.

"It's due to the industry challenges," Sterling spokeswoman Cara Coon says of the big increase. "Banks continue to fund this. We do view this as our responsibility."

The FDIC, which raised deposit insurance premiums sharply in 2008 and 2009, said the prepayments of deposit insurance assessments for 2010, 2011, 2012, and the fourth quarter of 2009 totaled $45.7 billion.

"They were able to hit their target," says Chris Cole, senior vice president and senior regulatory counsel of the Washington, D.C.-based Independent Community Bankers of America, a banking industry association.

At that organization's national convention in Orlando, Fla., last week, Deckard attended a luncheon with FDIC Chairwoman Bair and about 18 others. Asked how Bair saw the climate for future deposit insurance assessments, Deckard says, "Her comment was that while there are signs of economic recovery, there's continued stress on asset quality, and they see continued pressure on bank earnings. She's sympathetic to an end to 'too big to fail.'"

Because big banks have other sources of funds besides local deposits, they take outsize risks, leaving small banks to carry a disproportionate share of the cost of insuring deposits, Deckard says. He says community banks are lobbying Congress to change that.

The FDIC said the three years of prepayments wouldn't hurt the banking industry's earnings because they would be recorded on banks' balance sheets as prepaid expense, then moved to their income statements in increments and taken as an expense against quarterly earnings.

Peter Stanton, chairman and CEO of Washington Trust Bank, says that at least the FDIC's decision to require payment of three years' worth of premiums upfront eliminated some uncertainty.

"I think most of the industry felt it was a better option than not knowing what the amount was going to be for the next two or three years," Stanton says. "At least it's an amount we can budget, and hopefully it will not be changeable." Washington Trust, which is privately held, declined to release the amount of FDIC premiums it prepaid, although Stanton says, "It was a substantial increase."

When the FDIC's board of directors voted in November to require the prepayment, the Independent Community Bankers of America said it was "pleased that option was chosen rather than levying one or more additional special assessments—something that would have impeded lending in cities and towns during this critical time."

The FDIC said, "The payments will come from the industry's substantial liquid reserve balances, which as of June 30, totaled more than $1.3 trillion, or 22 percent more than a year ago."

The FDIC levied a special assessment against banks last June 30, payable Sept. 30, 2009, that cost Inland Northwest Bank $115,000 and Wheatland Bank $31,000.

When it mandated the prepayments, the FDIC also added 3 basis points, effective for 2011 and 2012, to the rates it assesses banks to insure each $100 of deposits. One hundred basis points equals 1 percent. The FDIC's assessment rates are 17 to 77.5 basis points per $100 of insured deposits now, depending on which of four risk categories applied to a bank.

A bank's assessment rate also varies based on a complex formula that takes into account its so-called CAMELS regulatory rating of its capital, asset quality, management, earnings, liquidity, and sensitivity to interest rate risk. Banks are required under the law to keep their CAMELS ratings, determined by federal and state bank examiners, confidential.

Fewel cautions that there's no guarantee the FDIC won't require another increase in premiums later.

"We are all worried about that, that there might be another special assessment," Fewel says.

The FDIC has said that 140 banks failed in the U.S. last year, and through March 12 an additional 30 had failed.

Stanton says it made sense for the FDIC to require the prepayments "to get that much cash in up front when they're dealing with the worst of the problems banks have, even though we were somewhat dismayed at what we're all paying."

Even though the sizable prepayments didn't hurt banks' income statements, institutions still had to come up with large amounts of cash to make the hefty prepayments, Stanton says.

"It's easier for a bank to come up with that kind of money than it is for a regular business," he says. "It's our inventory."

Still, he says, "We feel like we're paying for the sins of the others." That occurs when the FDIC uses money paid into its insurance fund by stable banks to cover the deposits of customers at poorly run banks that fail.

By paying the deposit insurance premiums, "the industry funds its own losses," Stanton says. "It's not coming out of the taxpayers' hides."

Fewel says the prepayments have one downside that shouldn't be overlooked, and that's the earning potential banks have lost by paying the premiums early.

"What could I have earned on that cash if I could have kept it?" he asks. "I'm buying bonds today at 4.25 percent." That would have brought in $119,000 in pre-tax income to Inland Northwest Bank in one year and close to $300,000 in revenue over the three years, Fewel says.

"That's gone," he says.

Latest News

Related Articles

![Brad head shot[1] web](https://www.spokanejournal.com/ext/resources/2025/03/10/thumb/Brad-Head-Shot[1]_web.jpg?1741642753)